Though an individual exhibit not always puts the artist’s work in the limelight of enthusiast and plentiful publicity –due to the artworks’ conception– and he or she doesn’t even get the kind of media hype he or she expected, the overall insertion of the artist’s work in the pages of a monograph exempts him or her from the unfulfilled expectations. The exhibitions of paintings, sculptures and installations are seldom memorable –I wish that were not the case, but they are definitely fleeting, that explains the importance of such event’s main catalog as a proof of its realization. Its importance as a reference tool for critics and for salespeople willing to put the artworks on the market is paramount. What can we say then about the permanent status of memoirs and monographs? A look into it is mandatory and never comes too late, no matter if it was not put out as soon as the event was over.

Pedro Avila Gendis is a Cuban abstractionist painter of rock-solid professional formation, with an abundant work and a highly-achieved esthetic proposal. However, its stance in the insular artistic scene is discreet, let alone unrecognized. The book published about him in Colombia now sort of offsets this shortfall of recognition about his artwork, marked –among other reasons– by the lack of a printing infrastructure designed for art-oriented publications –a situation that’s now beginning to be reverted in our region.

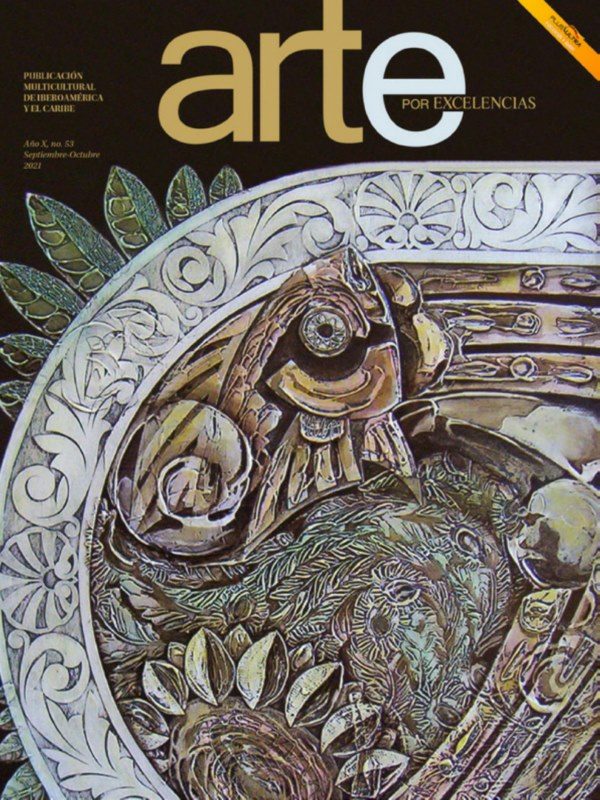

The book compiles Avila Gendis’ pictorial work between 2001 and 2006, paintings made on canvas, cardboard and paper with oil pigments and acrylic, featuring strongly textured suggestions, and an array of bright and motley hues, contrasted by light and dark pastes that lean to a progressively rainbow-colored atmosphere, though his compositions are equally ruled by a gesture-driven free spirit. Avila Gendis’ painting is pigeonholed in the so-called abstract expressionism and, within the framework of that trend, as part of the lyric-intended informal variant.

The book’s well-thought layout is made up of forewords written by poet and essayist Carlos M. Luis, a selection of criteria on some of the painter’s creative periods penned by Roberto Cossio, Virginia Alberdi, Pedro de Oraá, David Mateo and Tony Piñera. That kickoff is followed by the artist’s résumé and individual exhibitions, his participation in collective expositions, other collections he’s represented in and the list of works displayed in public spaces and institutions. There’s also a section containing documental and professional information, the index of reproductions embracing his latest works before the printing of the monograph. The only shortcoming worth mentioning is the lack of a small bibliographic list of articles, news clippings and catalogs so needed to enhance the information about the artist.

The critical pieces about Avila Gendis’ painting contained in the book’s introit help us delve into his visual poetry. It’s relevant to point out, first of all, the presence of the artist’s own external or introspective factors in order to understand his poetry. Carlos M. Luis refers to:

[the] stylistic confluences that always exerts influence on any artist’s work, no matter if he or she is not fully aware of them at all. The topic of the influences is something that can be conveyed through other means that appear to be up “in the air” without their being perceived in an accurate way. Each and every artist “breathes in” this same air his or her inner voice points him or her to.

I agree with this observation of suggestive appearance, and to this aim I allude it’s all about:

a typical phenomenon of modernity, that curious synchronization among artists from different nationalities and so distant from one another whose perceptions and expressions act like communicating vessels. On him [Avila Gendis] stands a tradition that dates back to the advocates of abstractionism in the early 1900s and reaches him in during the rekindling of the abstractionist movement.

In reference to the process of his pictorial creation –visionary thoughts and sensitivity– let’s put in Tony Piñera’s own words:

it’s as if you poured things into a melting pot and created a different matter. That’s how he controls the end result, like the personal digestion of what’s out there […] that manages to orchestrate the abstraction of variable ambiences, all that much worked out by the synthesis of what has been seen in non-artistic textured surfaces and environmental tropisms.

Nonetheless, not everybody sees eye to eye all along. David Mateo points out a difference:

in the process of artistic unveiling, anyone can recognize the existence of a rationale. The author doesn’t let impressions suck him in altogether, drag them all the way into a state of intoxication that might turn creation into a non-deliberate, intuitive fact.

And Carlos M. Luis jots down just another variant:

This fruition the artist feels when he starts working on what Raimundo Llul used to call the combinatory arts, leads to unexpected revelations.

And he concludes: “The contemporary art has embraced surprise as one of its properties.”

Avila Gendis’ painting could arouse a diversity of receptiveness. That’s how much suggestive and suggesting it really is. Dynamic in its traces, intense in its colors, the recipient of the soul of his temperamental restlessness.

Pedro Avila Gendis: Soul, Light and Color. Painting, the author’s edition, printed in Colombia, 2006, 112 pages.

Previous publication Cildo Meireles. Against hegemonic ideas in art

Next publication A Galician in The Caribbean

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022