In the region of Gibara, Holguin, in November 12, 1642, Christopher Columbus commissioned two of his crew, Rodríguez de Jerez and Luis de la Torre, to explore inland:

In the region of Gibara, Holguin, in November 12, 1642, Christopher Columbus commissioned two of his crew, Rodríguez de Jerez and Luis de la Torre, to explore inland:

The men returned in November 5. Jerez and Torres reported seeing gentle Aboriginal smoking huge tobaccos, the most surprising discovery in the first exploration of Cuba by the Spanish [Núñez Jiménez, 1989].

Columbian biographer Don Salvador de Mandariaga, in his work “Vida del muy magnífico señor Cristóbal Colón”, he said in relation to the important discovery of tobacco: "I had not found the great Can, nor the source where gold is born, but I had found something that it has risen since then more dreams than gold, which exerts more power over man than the Grand Can exerted on his subjects".

And as Columbus did not care about the crucial news, Madariaga said: "So we are blind to the favors of luck (...) when nature put him gold in the eyes in a new and inspired way. Columbus did not recognize it and let it go vanishing in smoke before his eyes without realizing its aroma '.

The exact day has not been able to be defined, between November 2 and November 5, when Rodriguez de Jerez and Luis de la Torre do so valuable discovery, because information is listed on the diary of Columbus, on Tuesday, November 6: " The two Christians found on the way many people going through their villages, women and men with a firebrand in their hands, herbs they used to make their incense.”

In the social and religious organization of the Taino, according to Christian the patriarchy existed, whose most important figures were the cacique and behique.

The cacique, main leader of each population settlement, organized daily tasks such as fishing, hunting or farming, distributed food and had absolute powers that his subordinates had to obey unquestionably and the behique [Dr. Manuel Rivero de la Calle defines him as a priest, sorcerer and doctor among the Indians] directed the ceremony of the cojoba or cohoba, the plant now called Tobacco –it is also read cobija, Cohiba and coiba--. Its dried leaves were ground into a powder, according to Zayas.

This ritual, related to its mystical world, was the most significant strength of the tribe and indocuban and West Indian spiritual culture. Its totem tradition took them to invoke the pantheon of their cemíes, which are part of the insular arauca mythology.

This ritual, related to its mystical world, was the most significant strength of the tribe and indocuban and West Indian spiritual culture. Its totem tradition took them to invoke the pantheon of their cemíes, which are part of the insular arauca mythology.

The Taino caciques spoke through the tobacco, with their gods, with their ancestors to communicate their vicissitudes, their diseases, both individual and those of the community. They were immersed in a magical-religious symbiosis request-help. It was the main center of the world for their beliefs.

Regarding this ceremony Las Casas describes us: "They had made some powders of certain very dry and finely ground herbs, cinnamon colored ... they put a round plate, not plain ... made of wood, smooth and cute, which was not more beautiful of gold or silver; it was almost black and looked like jet. They had an instrument of the same wood ... And with the same polished and beauty; the making of this instrument was the size of a small flute, all hollow as the flute and opened in two hollow canutos ... those canutos positioned in both two windows of the nose and the beginning of the flute, we said, in the powders that were on the plate they sucked with the gap inwards, and sipping they received by the nose the amount of powders they determined to take, which received from the brain as if they had drunk strong wine, they stayed almost drunk.

These ceremonials powders had cojoba ... in their language ... with this they were worthy of statues and oracles, by this way they discovered the secrets ... from there they heard and knew if good, adversity or harm were coming ".

Juan José Arron, the prestigious and deep investigador of the arauca culture, when referring to these conceptions, he writes:

"The Tainos believed not only in the return of the absent soul to the world of the living, but they also invoked their main ancestors in the rites of cohoba for them to foretell their future or provide support to hard tasks. That feeling of being spiritually united to their ancestors may have contributed the Tainos feeling confident and happy in their land, perfectly adapted to their environment, according to their subsequent fate. And that is why they were gentle and peaceful, and according to the testimony of Columbus, always talking with a smile in their faces. "

Many researchers have claimed that Cuban indigenous heritage did not persist, and have formed a called myth of extinction. But different direct field observations and documentation discovered in recent years have demonstrated the presence of the descendants of the Cuban natives in the eastern region of the country.

In 1995, along with Dr. José Barreiro, director of the Indian Program at Cornell University, USA, we visited the Rancheria, current municipality of Manuel Tames, and we met the cacique Panchito Ramírez Rojas and his family. We learned how the pride of being Cuban Indian beat in the feeling of that community.

We continue the work of Dr. Manuel Rivero de la Calle in this settlement and through hours of research, it was revealed a wealth of knowledge collected by Dr. José Barreiro in his book Panchito, the cacique of Monta:

"There are still in many of these families elders with significant generational orality on naturalistic themes, medicinal plants, planting methods, prayers asking for strength to elements of nature and other cultural and spiritual expressions."

In recent years of research work by Doctor José Barreiro and I, Panchito, Opulio --the oldest-- and younger surprise us one of those days of work in the countryside when they teach us that in their conuco they have a planting they call bighorn tobacco. And the tobacco was not like the many plants used in everyday life to heal and improved disease.

For them tobacco has a significant spiritual significance, and generations have passed a rite in a particular bond with their magical-religious world. This ceremony no longer involved the behique or emetic spatulas, but there is a main guide and community leader who has the powers of natural intelligence and respect of his people which allows him to guide, before the people, a ceremony of tobacco, with consequent symbiosis and acculturation process.

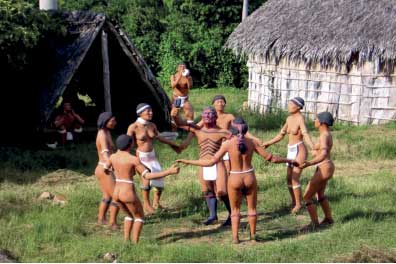

All settlement settlers gather in a circle and the cacique invokes the cardinal points and turns imploring the father sun, rivers, the rain, the wind, the grandmother moon, controller of women and stars.

In this ritual there is communication with their ancestors, requests for the needy and good harvests, happiness for all, love and peace for the universe.

The macuyo, as they call the wrapped snuff sheets, it is passed by the cacique after a pray to each of the participants, because it is the first offering made to the spirits, a bush or tree. Then they continue with praises songs of the ancestors expressing in typical rhythm, which are unique of the oriental son as Changüí, Nengón and Kiribá.

The tobacco and its charm expanded from our land and wanders today delighting men everywhere. It has taken in different cultures; it has become identity of all and has no borders. It has always been ahead of time, it has traveled many moons and suns. It seems that the Taino gods conspired to go beyond eternity.