Last February Marcos Lopez (Santa Fe, Argentina, 1958) inaugurated its 4th exhibition at the Fernando Pradilla Gallery of Madrid. Titled Local Color, the public could appreciate some lines of this remarkable creator’s work, represented in nine pieces of the last seven years. But beyond the space gained by Lopez in the Latin American photography, the fact of being promoted by a Colombian gallery located in none other than a former colonial capital, tells us of a longstanding phenomenon but growing: the internationalization of the payroll commercial galleries and with that, the visibility that figures in our continent have conquered in the international art circuits through a production focused on "the local", the way some segments of theglobal art system are operating.

However, not any look and construction of "the local" achieve recognition. His photographs of "staging", of unusual allegories and bright color can be considered a chronicle of these times. Not because of the character of the testimony inherent to photojournalist’s work, who is usually on the hunt for images and events that provide new information, but because they result from an artist that "creates and produces them" to use them for suggest, give to see, make a conscience… Marcos Lopez pre-visualizes what’s he then has to show us, having captured the essence of the world. But that world is Argentina, "from which he wants to talk",[i]and also America, "because Argentina is Latin America"[ii], but he insists that his look is from underdevelopment, that is, from the South and about the South. And for that, nothing better than the impact, the absurdity, the humor, the ambivalence, even the complacency and theemphasis made by color, or the weakness and the drama, if it is by its lack.

Local Color is, therefore, the prism through which he presents his reality and that of Latin America. At the same time, is a way of naming the shade that gives its characterization, through their spaces (which he re-built), of the beings that inhabit it and that he invents, or from his imaginaries and the archetypal configurations.

Local Color is, therefore, the prism through which he presents his reality and that of Latin America. At the same time, is a way of naming the shade that gives its characterization, through their spaces (which he re-built), of the beings that inhabit it and that he invents, or from his imaginaries and the archetypal configurations.

The search for an own color as an expression of (the) identity, is part of a personal discourse in which he has been working for some time, shortly before the digital coup, although some interests have marked specific paths at all times. He had its genesis in the first half of the nineties, when closing a chapter after the production of his series Pictures, executed in black and white. But while the color was the trigger or turning point of his production, we cannot ignore the importance of certain factors and experiences, from the hand of his talent and analytical skills, in the creation of his style.

A look at some passages of his biography, framed in the years before the reference series, the eighties, will allow us to know how the keys to his singular aesthetic were originated, whose essential features survive to this day. Marcos Lopez abandons the engineering career in fourth year, and like all self-taught, suddenly discovers his true passion, focuses on the practice of photography with vigor, and start making records of all the sceneries and targets arousing his interest: sports games in his school, rock concerts, families living in extreme poverty, as well as surreal inspiration sceneries he armed, while participating in workshops and activities at Fotoclub Santa Fe. Later, and being already in the capital, he works as a freelance at rock magazines, and in 1982 obtains a scholarship from the National Endowment for the Arts, which forced him to stay in Buenos Aires, where he has lived since. There he engages with other photographers: he exchanges opinions on their work, learns and engages in the development of exhibits that assess the value of photography as art. These were years in which he reaffirms the need of taking photos that generate "images with documentary and artistic value"[iii], demarcated from those for advertising, which earned easy cash, but whose frivolous perfection and idealism were inconsistent with his natural inclination to capture and recreate segments that revealed reality and were more committed. Little after he integrates the Photographic Authors Group, which was aimed at investigations, criticism and the defense of the author’s photography.

In addition to these initiatives from those youthful years it’sworth highlighting the links established -in the midst of the excitement for the recovered freedoms in the post-dictatorshipBuenos Aires- with artists engaged in the installation and performance as Liliana Maresca -a milestone of the art scene by her transgressor work inspired in the excluded and the marginal- who organized multidisciplinary samples at her home in San Telmo. And Marcia Swchartz -known for herneo-expressionist paintings, full of social criticism about the bohemian and hard-life characters- who participated with him and Maresca in collective projects as The Kermesse.[iv] With them he will discover the work of Antonio Berni, father of social realism, and that of Berni’s followers Alberto Heredia and Pablo Suarez; he will be in touch with other young artists whose innovative spirit will touch his bold part and will tempt him to test bold and modern images. Apart from the shared themes and sensibilities, these links motivated him to assume the photographyas a work of art: from a propositive attitude and from codes (color, composition, collage) and types of art as performance (the pose, the masquerade, transvestism); not to stay in the record of a piece of reality which would give a unique and transcendent image.

In those years he is interested in Photography Seminars held in Mexico, Caracas and Havana. They were events in which identity was being discussed, and also the photographer role, the importance of the testimonial work and thesocial commitment, issues that, while addressed within the broad regional photographic production helped him fulfill his desire to expand his gaze to the multifaceted reality of "the great America" (whose knowledge he had begun in short trips to Cuzco and Titicaca Lake while still living in Santa Fe), and that he could find in the pictures of Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Pedro Meyer, Graciela Iturbide, Paul Ortiz Monasterio and Sebastião Salgado. These constraints have their climax at the end of the decade, when in 1989 he becomes a member of the first generation studying at the International School of Film and Television of San Antonio de los Baños, school that will familiarize him with the world of sets and the springs which provide them with senses. But it not only teaches him to enunciate the messages from the articulation of "film frames". Through the relationship with peers, the school gave him an experience and a Latin-Americanist vision, key in his formation.[v]

In those years he is interested in Photography Seminars held in Mexico, Caracas and Havana. They were events in which identity was being discussed, and also the photographer role, the importance of the testimonial work and thesocial commitment, issues that, while addressed within the broad regional photographic production helped him fulfill his desire to expand his gaze to the multifaceted reality of "the great America" (whose knowledge he had begun in short trips to Cuzco and Titicaca Lake while still living in Santa Fe), and that he could find in the pictures of Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Pedro Meyer, Graciela Iturbide, Paul Ortiz Monasterio and Sebastião Salgado. These constraints have their climax at the end of the decade, when in 1989 he becomes a member of the first generation studying at the International School of Film and Television of San Antonio de los Baños, school that will familiarize him with the world of sets and the springs which provide them with senses. But it not only teaches him to enunciate the messages from the articulation of "film frames". Through the relationship with peers, the school gave him an experience and a Latin-Americanist vision, key in his formation.[v]

Just after 1989 and until well into the nineties, Gumier Maier will lead the gallery of the Ricardo Rojas Cultural Center of the University of Buenos Aires, and from there he will enthrone a light trend that soon it will be felt in the local scene.[vi] The decorative, beautician and kitsch guidance of the Rojas, paradigm and symptoms of an epoch, will be imposed as fashion and will encourage its adoption, even by those who are not indifferent to the socio-political conflicts. For the latter the aesthetic light -though apolitical- will be the facade in which messages such orders can be camouflaged, while it will be difficult to escape the fascination of its brightness and color, not to succumb to its seduction, and stop tempting a visual that quickly gained popularity. In fact, in 1996, already consolidated his personal style, Marcos Lopez made his first major solo exhibition in Buenos Aires. And although his work had an explicit reference to the situation that Argentina was going through, it could be seen in its visual vocabulary -the color brightness, the ornamental tone, and the (apparent) frivolity -some air in common with artists of the Rojas.

A few years earlier, his progressive dissatisfaction with linguistic patterns prevailing in his trade and in the eyes ofthe course of events, will lead him to equally critic positions in both levels. On the one hand, toward the conventions of traditional photography noted in the portrait rhetoric, in the monitoring of strict regulations (prevailing in his province, but also in shops of the capital) regarding the composition and the message that the image should carry; and, most particularly, to consider the shot as the only way of registering the real. On the other, toward the false prosperity used by neoliberal politics, festive preamble of the alleged entry of Argentina into the First World, as it was becoming evident the increase in social inequality and the rampant inflation after the crisis of the powerful national industry at a disadvantage against transnational capital increasingly expanded. The confluence of all these factors will create the conditions to produce a moment of rupture and the emergence of a totally new work: photography of staging, a masquerade in close-ups, wide angular, full of joy and color, which had its finished expression in Buenos Aires, the city of joy.

This work in 1993 will integrate shortly after his famed Latin Pop series: the documentary record of Menem, the aesthetics of painted cardboard, the Argentina of the shopping center. The Argentinian critic Valeria Gonzalez will notice the ironic and questioning sense enclosing the adoption of this current of the 1st World art.[vii] The establishing measurement that merchandise and consumption goods in American pop reached in the sixties is broken by a bad made copy, contaminated by the presence of kitsch drawings (Menem faces with political criticism purposes) and by the excess of color, in order to enhance the image imposture and at the same time its realism, while the representation becomes decorative and satirical.

Henceforth, the color will underpin its staging over the contrasting Latin American modernity and known parodies about the milestones of the Continent photography and classics of the Western art history. Also it will give dramatic qualityto the pieces of Red ink, and it will animate with its tones the recreating of myths and figures of our history as part of his poetics of the local pop.

In a context aimed at the deification of the trinket, the imported objects and the Taiwan-made cellphones,the recovery of vernacular culture expressions become meaningful, stronghold of regional identity. Looking back to the representations and stereotypes of Latin-American popular culture, part of the collective imagination, is one of the imperatives of the moment. Thus, after the gestation of characters that embody the masquerade Menem and the anonymity of those starring scenes about products for sale, he focuses his attention on the "real" icons of America. Lopez admits the fascination that the work of the Mexican muralists exerted always on him, including Diego Rivera, who in one of his most famous murals deployed and mixed myths and historical personalities -Frida Kahlo, José Marti and Emiliano Zapata, among others- with workers, rich men and figures of popular tradition as the skull. It’s not surprising that in 2000 he drafts a Latin Americanist manifesto declaring himself the "Diego Rivera in the digital era", "the Diego Rivera of the Pampas".

Bolivarian Suite (2009), one of the nine pieces exhibited in Local Color, remembers that great fresco about the popular culture and the history of the famous muralist, although he violates its compositional structure, visual substrate and the draft of the national to extend it to almost all America. Built by way of a great collage and through digital assembly he situated in a wall as background -where a barbecue grilling gives the local note- to the great leaders and heroes of the Latin American history and current situation; later, to emblematic important figures of the Argentinian culture as Gardel, Evita and Peron -whose busts turned rubber toys float in a pool- sports idols, and the stereotypical image of the American soldier's epic on the World War II, all of them together with complete nonchalance on a floor covered with containers, covers and other objects with faces of stars and advertising images, that stand out by its colors polyphony. At the mural’s background, neighborhood roofs give the sense of periphery. It’s a parody of the mural, from the obvious of the portrait, the cultural references and the market aesthetics and the kitsch.

Bolivarian Suite (2009), one of the nine pieces exhibited in Local Color, remembers that great fresco about the popular culture and the history of the famous muralist, although he violates its compositional structure, visual substrate and the draft of the national to extend it to almost all America. Built by way of a great collage and through digital assembly he situated in a wall as background -where a barbecue grilling gives the local note- to the great leaders and heroes of the Latin American history and current situation; later, to emblematic important figures of the Argentinian culture as Gardel, Evita and Peron -whose busts turned rubber toys float in a pool- sports idols, and the stereotypical image of the American soldier's epic on the World War II, all of them together with complete nonchalance on a floor covered with containers, covers and other objects with faces of stars and advertising images, that stand out by its colors polyphony. At the mural’s background, neighborhood roofs give the sense of periphery. It’s a parody of the mural, from the obvious of the portrait, the cultural references and the market aesthetics and the kitsch.

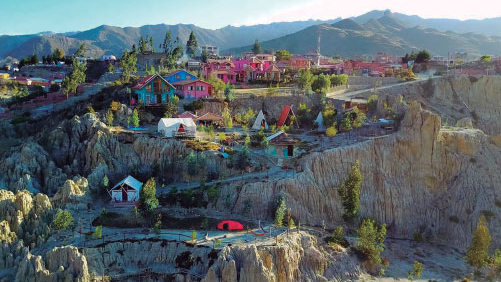

But he not always needed to prepare the scene. A typical restaurant in the city of La Paz urges him to registration. Bolivian Restaurant (2010), a feast of traditional textiles and commercial-made with kitsch motifs, repertoires of the political and the religious in motleycoexistence and colorful, it talks about the ways in which local people decorate the spaces with images of their choice and with spontaneity. It is a work that exemplifies his reunion with documentary photography.

Some critics claim that this photography is conceptual, and not without reason. In Motherland (2011) he proposes a stark and critical reading of this concept. He doesn’t do it from its stereotype -that figure "exceeded of significance" as Rodrigo Alonso defines-[viii] as the "Motherland" (Spain) lacks any fixed semblance, but from a perspective of Latin America itself, in the figure of the young mixed-race girl, target of the Spanish conqueror’s gaze. Through sensuality emanating from the neck of the young girl, Marcos Lopez not only reveals a dark side of the episode of Conquest, but how can the Motherland even see us: as the object of desire. I don’t rule out that in the eroticism[ix]icon is included the young girl perspective and the provocation she knows she can arouse. Diptych structured, the piece has in its right side a close up of the neck, from which is hanging an imitation chain with a pair of figurines, allegory inducing an unambiguous interpretation. Thus, in the inter-textual relationship between the two parties we find the maximum productivity of its reading, open to comments on the power relations in the gender problem and its intersection with the metropolis topic.

Another different reading give the photos Girlin Latvia and Basketball boy in Latvia (2011), taken of his students in a photography school where he taught a workshop. These two works, as in no other work in the sample, relate how gone are the humor and joy that characterized Buenos Aires, the city of joy; the sarcasm in them has given way to sadness. These are incursions in the body image, tempting the meanings enunciation in simple environments, from work with the face and form, and with the effects that can give light and color. For example, the young people paleness is aimed at representing their country of origin (Latvia) distant from Latin America (which is characterized by a vibrant color). The muted tones of the images (hand-colored) reinforce the sense of existential drama, and contrast with the brightness of the palette Neighbors (2011).

In this last work we find that he addresses the photo from a pictorial place.[x] Not only because large color planes associate it with the pop and its manners with the French School, but because evidence that is not enough the simple photographic register and it requires the expressive explosion and the aesthetic enjoyment given by color, intensified deliberately. In the introductory text in the Pradilla Gallery he leaves it explicit: "I always want more. I reconcile withlife going through excess. To get balanceI prefer to add instead of taking”. As well as the typicality of the scene, a couple in front of his home in Barracks at the summer sun and drinking mate, this resource also allows him to overcome the literal image data : the people in the photo are no more just neighbors, but "characters", archetypes of a place. Just in that lies his art.

In this last work we find that he addresses the photo from a pictorial place.[x] Not only because large color planes associate it with the pop and its manners with the French School, but because evidence that is not enough the simple photographic register and it requires the expressive explosion and the aesthetic enjoyment given by color, intensified deliberately. In the introductory text in the Pradilla Gallery he leaves it explicit: "I always want more. I reconcile withlife going through excess. To get balanceI prefer to add instead of taking”. As well as the typicality of the scene, a couple in front of his home in Barracks at the summer sun and drinking mate, this resource also allows him to overcome the literal image data : the people in the photo are no more just neighbors, but "characters", archetypes of a place. Just in that lies his art.

Under the bias of a contemporary visual art, other aesthetic keys could be seen at three pieces of Local Color, from the series National Surrealism: Constitution Corner (2005), Barracks Corner (2005) and Adidas Corner - Constitution (2010). They are urban corners of the deep Buenos Aires, full of “trucha” advertising, almost decadent, which therefore serve him to reveal what he has been called "the texture of underdevelopment". Through staging related to film production -where he makes choreography with human groups to the tableaux vivant way- he shows his critical view of the sociocultural reality of the city, inconsistent with the ideality that market ads show. And just such a backdrop that is part of the reality -haloed by painted cardboard signs of domestic products and commercial trademarksof Development- willmake him reflect on the coordinates that govern life in Argentina and in other sceneries of unfinished modernity. In Barracks Corner the location of people in indifferent poses or with their back to the big Coca Cola fence that says "You're not extra, you give climate to the scene," reveals how society washes its hands in reference to advertising propaganda, while underscoring the futility and deception of the slogan, for that scene doesn’t exist and no one is involved in it. Something similar can be seen in Adidas Corner, although here there is a dominion of irony on the homogenizing effect of the transnational market and its paradoxes in the Latin American context. For this he repeats the logo on the garments of all the people passing by, he highlights it diversifying its color by digital manipulation, and from the posing of massive consuming brand, to deny that this is what happens in reality. The irony is completed when we realize that the common characters that carry the logo don’t comply with the advertising stereotype.

The disconnection between people and (the unreality of) the advertising generatesan atmosphere ofalienation, which, for different reasons, we could also see in the urban scene that gives closure to the futuristic film The Matrix. They are pieces about the aspirations and misunderstanding with the global economy and culture, where the scene‘s assembly, the digital retouching and the artifice of the hand-colored photo are based on the added value of their reflections.

[i] GABRIELA ESQUIVADA: “Interview with Marcos Lopez". In: Hojas del Rojas, July 2001.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] ALEJANDRO CASTELLOTE: "Interview with Marcos Lopez". In: Buenos Aires to Madrid, October 2006.

[iv] GABRIELA ESQUIVADA:Op.cit.

[v] In conversation with the artist.

[vi] While the Rojas was the starting point, Victoria Verlichak explains that Gumier Maier saw multiply the effect of his work through the incorporation of its artists to exhibitions at prestigious locations in Buenos Aires as the ICI (Institute of Latin American Culture), the National Museum of Fine Arts and the Ruth Benzacar Gallery. Cfr. VICTORIA VERLICHAK : "Gumier Maier. An intermittent artist". In: The eyeof the beholder. Artistsof the 90s. Proa Foundation, Buenos Aires, 1998, p. 15.

[vii] In the book's foreword National Sub-realism, published in 2003, Valeria Gonzalez argues: "... the reference to a 1st World style of the contemporary art works less as a modernizer element of his photograph, that as a catalyst for a critical observation of his own political and cultural environment. Lopez takes the imported model to 'pronounce it wrong', to transgress it, to reverse its original sense. In his images nothing remains of the optimism and the formal moderation of the art of the sixties. The pop Art resources undergo a hyperbolic overload that becomes them a theatrical parody of a masquerade”

[viii] RODRIGO ALONSO: "The Discovery of America will not happen. Latin America as a parody”. In: Do not know,no answer. Contemporary practicesfrom Latin America. Art x Art Editions, Buenos Aires, 2008, p. 37.

[ix] Regarding treatmentof eroticism, note the difference between Homelandand its parody of Sunbathing on theterrace, which original becomes a male, hedonistic and local version. Cfr.JUAN ANTONIO MOLINA: South ofrealism. Marcos Lopez Solo Exhibition Catalogue, Cadiz, Spain, 2004.

[x] JOSEFINA LICITRA: "The man and the little mermaid". http://revistanuestramirada.org/galerias/marcoslopez

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022

Giovanni Duarte and an orchestra capable of everything

August 26, 2020