Negret already chanted his chant.

His voice is powerful and his song poetry.

There has not been a chant like this that purifies depth and joy in one same voice.

In the fountain of his chant death will not water.

It is this same sorcerer who has celebrated the sun for us, and has donated us his light that illuminates this daybreak that does not dawn, our already long eclipse.

“What rainbow is this black rainbow that rises?”[i]

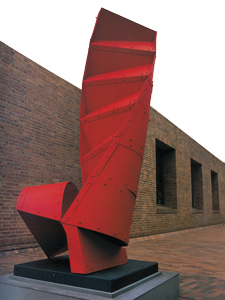

He already created his metallic suits and the wind let itself to be dressed, content.

He already dreamed for us, and left us precious metals that were not in the world before.

He already regaled us with his master class on independence, elegance and generosity.

A few years ago he concluded his work, his work that “would need a hundred years more to say what needs to be said”.

“Some said I was a madman. Others said I was a genius. And I was a sculptor”.[ii]

The silence of his hands dazes me.

From last century’s fifties, a plasticmovement was activated which notably sped up the contemporary art process among us. Alejandro Obregón initiated modern painting in Colombia, taking in as essential theme the geography, flora and fauna of this country, while Edgar Negret, then a resident in New York, with his Magic Machines (that should have been translated as “Máquinas Mágicas”) and his Kachinas, singing the aesthetics and magic of machines, founded contemporary sculpture in Colombia and in Latin America, an aspect that has not yet been studied, assessed and diffused in its right measure. As he did not participate in exhibitions and National Salons made in Bogota during his stay in New York, the commentators of the time did not review the evolution of his work during those foundational years, and did not adequately place it within the process of Colombian art. Recent historians that homologate Art History by dusting off newspapers, when they do not find it reviewed there, neither do they give it the place it deserves due to its previousness, its poetics, its belongingness, its significance and its influence.

From last century’s fifties, a plasticmovement was activated which notably sped up the contemporary art process among us. Alejandro Obregón initiated modern painting in Colombia, taking in as essential theme the geography, flora and fauna of this country, while Edgar Negret, then a resident in New York, with his Magic Machines (that should have been translated as “Máquinas Mágicas”) and his Kachinas, singing the aesthetics and magic of machines, founded contemporary sculpture in Colombia and in Latin America, an aspect that has not yet been studied, assessed and diffused in its right measure. As he did not participate in exhibitions and National Salons made in Bogota during his stay in New York, the commentators of the time did not review the evolution of his work during those foundational years, and did not adequately place it within the process of Colombian art. Recent historians that homologate Art History by dusting off newspapers, when they do not find it reviewed there, neither do they give it the place it deserves due to its previousness, its poetics, its belongingness, its significance and its influence.

The New York period was vital to the evolution of his art, since he adopted aluminum as the fundamental medium for his artworks, getting away from the traditional materials used in sculpture until then like wood, stone, bronze, iron; with techniques like carving, modeling, casting, smelting, forging and soldering. He created his work by cutting, bending, curving and fastening with nuts and bolts, in a beautiful and wonderful creative game; images of high formal and constructive complexity where imagination was paramount, marked in the shapes by the accuracy of an engineer and the attention to detail of a goldsmith though. Such an important stage for Latin American art, when together with his closest friends –Barnett Newman, Louise Nevelson, Ellsworth Kelly and Jack Youngerman-, he created outside the parameters imposed by the overpowering Abstract Expressionism movement of Pollock’s and Kooning’s, which captured all the attention and deployment of the press, of dealers, critics, cultural officials and galleries. In spite of it, Negret never felt tempted to adopt in his work the isms that were in fashion, and he rather placed himself on the side of an artistic resistance walled up between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art at one moment, and between Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism a little later. An artistic resistance he kept on practicing during all his sculptural exercise, and which constitutes an indisputable sign of the best Colombian art and the best Latin American art. Nevertheless, despite that “marginalization”, in the several exhibitions he made in New York, he always got favorable critiques to his work, which have not either been taken into account by our old and new historians.

The great failure of the Colombian critics and curatorship is evidenced by their inability to place, in the context of Latin American art, fundamental and significant artists from the country like Andrés de Santamaría (30 years before Reverón), Edgar Negret (whose arrival in New York is contemporary with the arrival of Jesús de Soto in Paris), or José Antonio Suárez[iii]. Colombian critics and curators that have never felt the need of a deep and smiling reflection that leads them to doubt about some aesthetic norms and a mimetic language that have been imposed on them. They have never faced up to the urgency of implementing a language that names other realities –concealed or denied-, because that nominative language would compulsorily be poetic, and they despise poetry, which they consider an unnecessary adornment.[iv] It is the arrogance of the new fundamentalists of the “avant-garde academy”, that in order to impose their aesthetic totalitarianism, they first decree the death of the avant-gardes (hiding their own aesthetic lair), in the same way in which neoliberals proclaim the death of ideologies, to globally impose their retrograde thinking of wild capitalism.

The language of post critics and post curators (who arrived late at art), being busy proving that the wit of variables is more important than the abyssal adventure of creation, is offensive. Their effort in putting the divertimento in use over art as an epiphany that makes us see the ethical encounter between authenticity and beauty is an insult to our intelligence and sensitivity. They have not heard that now that ethics has been expelled from the Law and the Economy, it has found a more certain home in poetry and the arts. Critics and curators who are busy proving that putting the Coca-Cola “C” in the word Colombia is a fundamental event in art, more necessary and meaningful than the work of artists like Edgar Negret, Carlos Rojas, Beatriz González, Oscar Muñoz, Doris Salcedo or José Antonio Suárez.

The language of post critics and post curators (who arrived late at art), being busy proving that the wit of variables is more important than the abyssal adventure of creation, is offensive. Their effort in putting the divertimento in use over art as an epiphany that makes us see the ethical encounter between authenticity and beauty is an insult to our intelligence and sensitivity. They have not heard that now that ethics has been expelled from the Law and the Economy, it has found a more certain home in poetry and the arts. Critics and curators who are busy proving that putting the Coca-Cola “C” in the word Colombia is a fundamental event in art, more necessary and meaningful than the work of artists like Edgar Negret, Carlos Rojas, Beatriz González, Oscar Muñoz, Doris Salcedo or José Antonio Suárez.

But the artists have already spoken. In what a lot of enlightening conversations with Carlos Rojas he told me over and over how important Negret is in Latin America, and how his work and his attitude were always an example and inspiration for him. Ramírez-Villamizar stated in an interview to El Tiempo newspaper (October 13th, 2002): “When I met Negret, he was enriched by two years of experience with Oteiza, and he passed all that knowledge on to me, enriched and elaborated once again by him in return. That encounter was very important to me and I always considered it one the most wonderful things that ever happened to me in my life. He is the most original and the most important artist that has ever existed in the whole history of Colombian art.” Jesús Soto and Sérgio de Camargo always acknowledged Negret as the great plastic artist of Latin America. The Basque sculptor Jorge de Oteiza, one of the most imaginative art theoreticians, has said that “Negret is the most important sculptor in Latin America and one of the greatest ones in contemporary sculpture.” And critics out there have also spoken: Juan Acha asserts that “without doubt, Negret has conceived one of the most important works in Latin American art and of the most up-to-date and beautiful ones in the world of sculpture”; Damián Bayón, “Edgar Negret is one of the main sculptors of this time. That he is one of ours, can do nothing but fill us with legitimate pride”; and Marta Traba, “he is, not only the best sculptor in Colombia, but the best in Latin America and one of the great figures in sculpture worldwide”. And the thing is, when reviewing his work and finding that among his sailors, bridges, buildings, metamorphoses, watchmen, stairs, cascades, the Andes, quipus, masks, moons and others –there are more than thirty masterpieces–, it indicates to us, no doubt, we are before the work of a genius artist. We are afraid of the word genius: the genius creates, ingenuity invents. Negret does not relate, does not comment, does not describe, does not scream, does not exclaim. His work is not derivative, not even thematically formal. Negret names, he is a creator, his sculpture is inaugural: “poetry is a soul inaugurating a form”[v]. He suppresses antecedents and comparisons and, at the same time, he is a bridge with the Western culture: “Every art, when deepening, shuts itself in and separates. But this art compares with the other arts and the identity of its profound tendencies sends it back to unity”[vi].Chillida himself, after talking about his Peine del Viento (The Comb of the Wind), his Homenajes a la tolerancia (Monument to Tolerance) and his compulsory retirement from being the regular goalkeeper for Real Sociedad due to a lesioned knee, asserted that “the most important and imaginative Latin American sculptor is Negret”.

The same way we recognize in Matta, Lam, Tamayo, Reverón and Torres-García the pillars of modern painting in Latin America, we need to appoint Negret, Goeritz, Clark, Soto and Fonseca the cornerstones of sculpture. Doubtlessly, Negret is for Latin America what Anthony Caro and Eduardo Chillida are for Europe. And it is precisely a comparative study of the evolution of Negret’s sculpture with his European contemporaries what sharply reveals us his vitality, significance and belongingness:

The same way we recognize in Matta, Lam, Tamayo, Reverón and Torres-García the pillars of modern painting in Latin America, we need to appoint Negret, Goeritz, Clark, Soto and Fonseca the cornerstones of sculpture. Doubtlessly, Negret is for Latin America what Anthony Caro and Eduardo Chillida are for Europe. And it is precisely a comparative study of the evolution of Negret’s sculpture with his European contemporaries what sharply reveals us his vitality, significance and belongingness:

- First abstract sculpture: Negret 1950, Chillida 1951, Caro 1960.

- First metal sculpture: Negret 1949, Chillida 1951, Caro 1960.

- First polychrome sculpture: Negret 1956, Caro 1960.

- First sculpture without a pedestal, placed directly on the ground: Negret 1963, Caro 1960.

- First solo exhibition: Negret 1943, Chillida 1954, Caro 1956.

- Sculpture Prize at the Venetia Biennale: Negret 1968, Chillida 1958.

It is just that over there, writers, philosophers, universities, directors of biennials, museums and art encounters, the private sector and even the gray public officials have been paying attention to acknowledging, studying, taking care of, spreading and acquiring his works, while over here, our cultural bureaucrats and curators are shaken by the portentous concept behind the “C” in Coca-Cola and, in a traffic of influences that is impossible to conceal, they spend an enormous and unjustifiable amount of money in works and events that lack sense and significance, which are an ignorant affront to the very same people of the arts in a poor country like ours. “Truth does not oppose error, but false appearances”, Foucault tells us. Is it not an obligation of those who hold the economic, political and cultural power to have acquired a long time ago a sufficient and coherent series of Negret’s sculptures so the common people can know them, feel them, study them and, while they are it, to have granted him the acknowledgment and company he has needed so badly? Is it not an inescapable obligation of those who hold the economic, political and cultural power not to allow his exemplary teachings to dilute?

But his lesson has not only been poetic. It has been, above all, humane, ethical. Ethics is not a treatise, it is not a technique. Ethics becomes evident in action, in acting, in doing. “It is no longer just an aesthetic search, but also, and ethical encounter. […] Only the great art is ethical. It arises from its origin as an expressive necessity. And its source –the source from which it receives nourishment- is not what is on the outside but what is very close and profound. Not what is foreign but what is intimate. It arises from the being and asserts itself creating its own ground and founding its own truth”.[vii] Its roots, deep and alive, do not cast shadows. And as a truly ethical being, the man and the sculptor walk, holding each other tightly, along the same track. That is why the refinement, the joy, the absence of nostalgia, are the same in works and man. The beauty of the works is the same of that in the man’s soul. And beauty is shelter neither for cowards nor for mediocre ones. Then, without any obligation to expiate a sin, we love beauty because “we recognize it as what it truly is, not the anemic goddess of academies but the friend, the lover, the partner of our days”.[viii]

But his lesson has not only been poetic. It has been, above all, humane, ethical. Ethics is not a treatise, it is not a technique. Ethics becomes evident in action, in acting, in doing. “It is no longer just an aesthetic search, but also, and ethical encounter. […] Only the great art is ethical. It arises from its origin as an expressive necessity. And its source –the source from which it receives nourishment- is not what is on the outside but what is very close and profound. Not what is foreign but what is intimate. It arises from the being and asserts itself creating its own ground and founding its own truth”.[vii] Its roots, deep and alive, do not cast shadows. And as a truly ethical being, the man and the sculptor walk, holding each other tightly, along the same track. That is why the refinement, the joy, the absence of nostalgia, are the same in works and man. The beauty of the works is the same of that in the man’s soul. And beauty is shelter neither for cowards nor for mediocre ones. Then, without any obligation to expiate a sin, we love beauty because “we recognize it as what it truly is, not the anemic goddess of academies but the friend, the lover, the partner of our days”.[viii]

Villagrande

[i] Atahualpa

[ii] Negret

[iii] Doris Salcedo does have her place, but she does not owe anything to anyone: she is internationally renowned for her own projection ability.

[iv] A famous Colombian theater director advised not to read poetry because of its depth and complexity: “half a poem is enough”, he shamelessly affirmed.

[v] Jouve

[vi] Kandinsky

[vii] A. Montaña on Negret

[viii] Camus

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022