(Presentation text of the catalog: Pabellon Cuba, Havana, May 13 of 2011)

By David Mateo

Cataloguing has been one of the main problems faced by Cuban plastic art over the past few years. The absence of financial resources on one hand, and the lack of initiative and management capacity on the other one have taken the situation to critical levels. Very few galleries are in a position to assume the edition of catalogs of the work of the artists they represent or the trends or expressions they legitimate. There is total lack of this type of generic catalogs that show the development of our artists in the different fields of art: painting, video, installation, photography, design, engraving or performance. Artecubano, La Gacetade Cuba, the digital newsletter issued by Casa de las Americas, the Arte por Excelencias magazine are the only publications so far systematically working to fill the information gap suffered in the plastic arts in the island, but they cannot cover by themselves –because of their issuing frequency, profile and selective criterion–the whole dynamic and diversity of the Cuban plastic movement. Except for important events like the Havana Biennial, most exhibiting events are passing over without leaving written, bibliographic proof. I have said it once already and I will repeat it in this presentation: the Cuban plastic memory–with all the risks and preconditions concerning value and distribution it entails– depends on individual, private initiatives. Not that I am against or skeptical about this variant within the field of artistic promotion, on the contrary, I think it needs to be supported and encouraged though not as the only or most efficient option but as a complementary or parallel alternative. Many times I have asked to myself: what is it that actually hinders, inhibits the initiatives of our galleries, centers, institutions and museums to look for financing sources and produce books or catalogs that could be as valuable as Memoria, artes visuales siglo xx (Memory, Visual Arts 20th Century), El nuevo arte cubano (The new Cuban art), or the monographs of Mariano Rodriguez, Amelia Pelaez, Eduardo Abela, Victor Manuel, Flavio Garciandia, Belkis Ayon or Jose A. Figueroa?

If this a problem conspiring against the promotion of artists who have already built a career or won some national recognition, then reality is not very encouraging for that generation of young creators coming out year after year from the San Alejandro Academy’s classrooms, the Higher Institute of Art, from any community cultural center, association or school of the country. Even if their work is good enough as to be early represented by galleries, to appear in relevant exhibitions and contribute to enriching the Cuban visual panorama, would they have to wait until their works of art are famous and valuable enough so they can afford cataloguing them on their own? Who would put on printed materials and images the evidence of those processes of continuity and renovation of those artists that have emerged within more than one decade ago?

For one moment I thought that the answers to some of these questions would continue to be held forever, and that such delay would affect the artists that emerged in 2000 in the same way it affected those who came out in the 1990s, the period in which there was not correspondence between the intensity of artistic actions and events and their print documentation. If it were not been for books like Nosotros, los más infieles (We, the most unfaithful), a compilation of Cuban critic’s reviews from the 1990s recently edited by Andres Isaac in Spain, it would have been very hard, for example, to know whatCuban critics thought and said during those controversial years. But still: where are the visual testimonies of projects like DUPP, Las metáforas del templo (Metaphors of the temple), Vestigios, un retrato possible (Vestiges, a possible portrait), Vindicación del grabado (Vindication of engraving), Amistades peligrosas (Dangerous Liaisons), El oficio del arte… (The trade of art). I think only photography and engraving were registered those years in a catalog fit for some artists and the most important events.

The catalog recently edited by AHS: El extremo de la bala, una década de arte cubano (The end of the bullet, a decade of Cuban art) has been able to contain to a certain extent the skepticism around the spreading of information; it has made us realize that there are many people who share the same questions and need answers, be it creators or leaders. This editorial project settle a debt with the need to leave proof of the day, of the moment, the present, when it is still not too late, when many young artists credited on its pages are still –as rightly written in the introduction of the catalog– vulnerable, insecure, changeable, susceptible, and who have not become successful characters yet like Los Carpinteros, Garaicoa, Kcho, Esterio Segura, Alexandre Arrechea, Carlos Quintana…, who maintain a permanent link with the national and international gallery network, and can assume the self-production of their works of art, exhibitions and even their editorial medium.

The catalog recently edited by AHS: El extremo de la bala, una década de arte cubano (The end of the bullet, a decade of Cuban art) has been able to contain to a certain extent the skepticism around the spreading of information; it has made us realize that there are many people who share the same questions and need answers, be it creators or leaders. This editorial project settle a debt with the need to leave proof of the day, of the moment, the present, when it is still not too late, when many young artists credited on its pages are still –as rightly written in the introduction of the catalog– vulnerable, insecure, changeable, susceptible, and who have not become successful characters yet like Los Carpinteros, Garaicoa, Kcho, Esterio Segura, Alexandre Arrechea, Carlos Quintana…, who maintain a permanent link with the national and international gallery network, and can assume the self-production of their works of art, exhibitions and even their editorial medium.

El extremo de la bala… goes beyond the category of a catalog and almost becomes a book, and –like the curatorship that justifies it– proposes a selective inventory of more than 90 young artists who have emerged from all over the country with a suggestive, promising work within the so-called conceptual art and any of its variants and which are representative within painting, photography, video, performance, sculpture and installation. It is true that within the group suggested there are a few names that are unmistakable because their work achieved early recognition and have caught the attention of gallery owners, critics and Cuban and international curators, such is the case of Duvier del Dago, Douglas Argüelles, Adonis Flores, Hender Lara, Marielena Orozco, Michel Perez, Ruslan Torres… But this is only obvious to specialists on the matter because the catalog, in general, follows a logical order, an interrelation that favors the course, the reading, the decoding of contents, and contributes to the credibility of that panoramic view, of the exploration along the decade led by the organizers. El extremo de la bala… provides enough evidence of today’s acceptance of certain aesthetic and conceptual proposals, many of them going back to the eighties and nineties; it corroborates the validity of works with a marked social-cultural connotation, and the impact of themes and concerns related with the dichotomy of individual-context, truth-appearance, public eventuality-private eventuality.

Although it is a pretty synthetic and condensed catalog, El extremo de la bala… rationalizes very well the spaces dedicated to each of the included artists by means of extremely functional informative blocks each including a summary of the curriculum and a picture of the artist, a personal statement, and a set of emblematic images with an acceptable resolution level, that made it possible to have a rapid and efficient characterization of the artists and their work.

The design is a resource effectively used in this catalog contributing to its coherence and visual unity. It does not happen what in other similar experiences that design tries to become an independent element, separated by ostentation or graphic flaunting from the contents it enhances and promotes, on the contrary, it is a tool that conspires, strengthens the expressive and metaphoric ability reflected by the images from both the individual perspective and as a whole. It is, from my point of view, the first element providing the catalog, edited by the Hermanos Saiz Association jointly with the Cuban National Council of Plastic Arts and the Higher Institute of Art, with credibility and attraction.

Even though a catalog like this one, in which other young artists could have been included, the selection made by editors and curators is not, like in other cases, a guarantee of permanence and artistic success, we are certain that the initiative will be highly welcomed by artists, art critics, students and historians thirsty of seeing the work of Cuban plastic artists inside and outside the country. This is not just any catalog; it is not the evidence of what was set to be at a given moment a mega-exhibition about emerging Cuban art, but an indispensable testimony of creativity, challenges and perseverance that we have experienced within Cuban art during the last ten years.

Related Publications

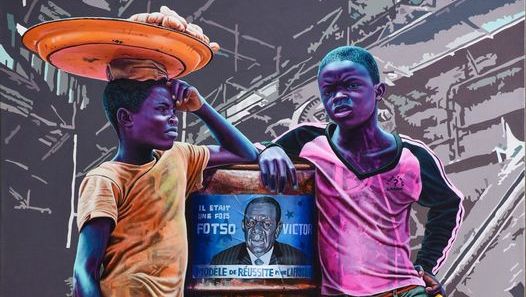

Catalogue "Smiling and Suffering"

June 03, 2022

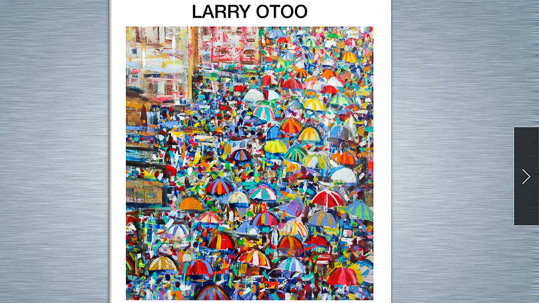

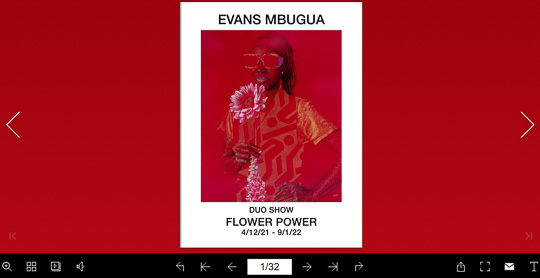

Catalogue Flower Power

December 01, 2021