By: Rafael Acosta de Arriba

We are not far away from other people: we are far away from ourselves.

Octavio Paz

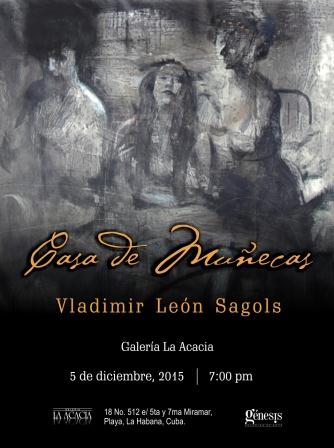

Every time I see a new work by Vladimir León Sagols I realize the truth in the statement that art is not meant to be understood. We will never be able to understand the imagery of this creator if we use the usual yardsticks. His plastic discourse escapes the most linear rationality. Perhaps it is only possible to intuit a certain notion of where he is headed for. The core of his oneiric world in any case belongs to him alone and no one else. It is a unique, exclusive repertoire, a domain in which the fabulation that Sagols is capable of overflows any classification. In the same manner as I say this, I also affirm that he is one of the most interesting and attractive painters and sketchers in the country. It is common knowledge that art is not meant to be understood, but to be felt, for our emotional intelligence to connect with its essence.

What is the meaning of the “dollhouse” the artist proposes to us? Can anyone tell? In my particular case I elude the answer. However, I will passingly note down some comments about the display. The exhibit is an inward stare, an introspection by the artist into his inner world. To the onlooker it is like attempting to see at night in an alley with barely an oscillating dim light. Still, the idea of a “house” has a fleeting presence in several of the paintings. Once again Sagols invites us to enter his premises, this time with more precise figuration than in previous exhibits, but with a not less ambiguous and mysterious message. A house can also be a place for reclusion, a site to gather or concentrate women. A certain eroticism continues to accompany his series, but it is an erotic sensation not openly manifested. It is just that, a sensation, like a hand that ends up caressing a half-naked body or bodies forecasting avidity, offering themselves to the taster, though we will finally not know whether desire was their intentionality. The naked or half-naked bodies of women (are these the dolls?) rotundly appear in most of the paintings as providers of signs illuminating the dim surroundings, the body image deployed in its powerful visual semantics. Buttocks, breasts and waists breaking the visuality of the whole with their sensual power. It is a vision of eroticism very much his own, a stare at the resplendent feminine body within a rarefied or grim universe.

On the other hand, the supposed Dollhouse is only seen on few occasions, and only as a flicker. A naked woman in a fetal position is revealed to us inside a corset encapsulating her or imprisoning her, as if the idea of the series were to cloister these women in a small little house, an ambiguous if not absurd, or rather oneiric concept. Small little houses, barely a reference, appear in several pieces as if to illustrate the encrypted title. There are no dolls anywhere, not even an allusion to the childlike act of playing with such objects. It all lies in the artist’s abstract, turbulent mind, an already proven esthetic of darkness and few revelations, an esthetic of the encoded. Sagols is skillful at such optical manipulation. He challenges us slyly from his unassailable hermeneutics. That is his sense of art and he does it very well. Who could object to anything he does? We’d rather have to respect his creative coherence, his scant willingness to give his meanings away to us.

On the other hand, the supposed Dollhouse is only seen on few occasions, and only as a flicker. A naked woman in a fetal position is revealed to us inside a corset encapsulating her or imprisoning her, as if the idea of the series were to cloister these women in a small little house, an ambiguous if not absurd, or rather oneiric concept. Small little houses, barely a reference, appear in several pieces as if to illustrate the encrypted title. There are no dolls anywhere, not even an allusion to the childlike act of playing with such objects. It all lies in the artist’s abstract, turbulent mind, an already proven esthetic of darkness and few revelations, an esthetic of the encoded. Sagols is skillful at such optical manipulation. He challenges us slyly from his unassailable hermeneutics. That is his sense of art and he does it very well. Who could object to anything he does? We’d rather have to respect his creative coherence, his scant willingness to give his meanings away to us.

Once again the handling of human figures is both serene and tenebrous. Sagols does not look like anyone else in Cuban painting. His work probably contains something Gollian, a bit of the Eiriz mystery and Fabelo’s transworld of the 1990s, a bit from enigmatic, faceless Ponce, and a bit from Lucien Freud and Balthus, not so much from Klimt. Perhaps there is a bit of all those referents or there is nothing from them, but his seal lies in his indisputable originality. We know that this “digestion” of predecessors becomes shaded with the passing of time. In the case of our artist it is only a perception or a puzzle. His work is unique. He already has achieved a style of his own.

There are obviously no dolls, but only hallucinated beings in dark or reddish tones, the possible colors of the lowly, and some signs of underground worlds, a true challenge to the sharpest imagination. The strokes in the pieces exhibited are firmer, perhaps due to the use of drawing with charcoal and pastels instead of a brush, so that the morphology is more defined or academic than in previous exhibits.

In view of these paintings, one wonders once again about the meaning, not the symbol itself, but as anticipation of the scriptural in it. Spanish critic José Luis Brea has provided a very good description of this association, which dates back to the origins of human culture. How much scripture is there in the symbolic, Brea always wondered, and always, on meditating upon these pieces, I come back to finding much of silent poetry in the work of our artist. Following this line of thought, I feel that there is a certain association in these images with the essence of Les Chants de Maldoror, by the Comte de Lautréamont, the book provoking the inspiration of the surrealist movement. Even if Sagols had never read it, I perceive this disquieting presence in the hard core of the painter's imagery, the thirst for the infinite motivating Breton and his peers. It is a human pulsion, a sort of “visual grammar”, epicenter of all symbolic significance, and essence of that which semiology intends to disentangle. The artist attempts to name an experience beyond the retina, find a deeper key which is in fact no more than a knowledge experience.

The exhibit adds to a work that grows solidly in the Cuban pictorial panorama. Sagols’ symbolic production enters absolute maturity, and not because it has been decreed by a critic –in this case the undersigned, which would probably turned me into a laughing stock– but because it is self-evident, and that fact challenges any consideration to the opposite. His underworld of disturbing images may or may not be liked, but what is beyond doubt is his mastery and the hard core of a poetic that defies classification.

With respect to his previous exhibit at the last Havana Biennial, I have asked myself this question: What could be a more encouraging sign of the vitality of a work than when viewed as a whole some pieces appear fascinating and others disturbing? The mystery remains unveiled. Even more, I would say that the mystery of all of Sagols’ work remains unveiled, as well as his solitary presence amidst a tradition like that of Cuban painting. A tradition both risky and influential, at times distant, but often close enough to our artists. At a time when the youngest artists avidly assume the art codes most broadly disseminated in international art circuits, the Sagolian esthetic remains an impressionistic island amidst postmodern seas. To me it is a clear refutation to the so often cited “death of painting”.

It is surprising that the artist has created this atmosphere for such a naive, childlike theme. It is part of his way of being and his peculiarity as a creator. It is inherent to the way he sees art. The much expected –from the title– imagery of little houses, dolls, girls, bows and toys, is replaced by a viscerally adult world, sordid and dim, the Sagolian universe itself. The high esthetic value of these pieces is beyond doubt, irrespective of the standpoint from which they are approached. We are in the presence of spotless poetics, a form of visuality that creates fascination. Every time a see a new work by Sagols I become ever more interested in meditating on it and writing about it.

Related Publications

Experience Armand Boua's 'Manawa' at OOA Gallery

May 20, 2024

Albertina: Franz Grabmayr

May 17, 2024