If you’re not familiar with shunga, the early Japanese tradition of creating explicit images of sexual activity, welcome to the pleasure dome. Literally translated to “spring pictures,” shunga date back to Japan’s Edo period, from approximately the 17th to 19th centuries, when the country was experiencing a boom of economic growth and a new abundance of leisure time. That meant more art, more horniness, more erotica.

While Edo-era Japan was characterized by a strict social order, and sexual digressions like adultery were strictly forbidden, there was a designated space where more salacious desires could run free: Ukiyo-e, the floating world. This cultural bubble was a legally authorized safe space where sexual pleasure ruled paramount. Red light districts, brothels and kabuki theater were all designated areas where citizens could explore their sexual fantasies.

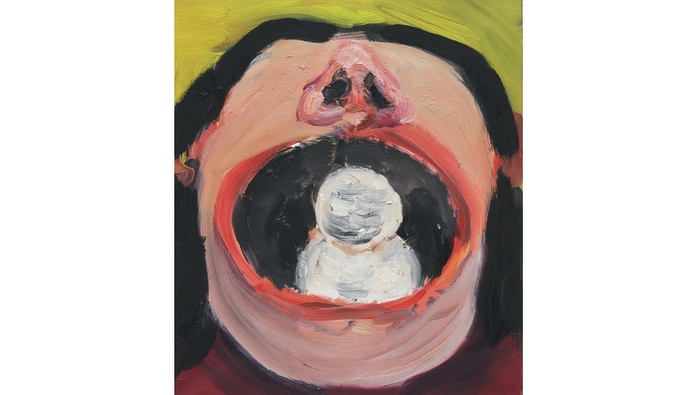

And then there was the shunga, ink paintings and woodblock prints depicting couples, mostly heterosexual but some queer as well, getting it on. The images are characterized by hyper-flatness, warped perspectives and bawdy humor, generally representing a giddy attitude towards sex, with all its pleasures and humiliations. Along with ecstatic facial expressions, both male and female genitalia are engorged generously, exaggerating every last hair, wrinkle and drop of moisture. Considering the puritanical understandings of sex that permeated Western Christian culture at the time, shunga is something of a beautiful anomaly.

The images were often commissioned by aristocratic males, though the artworks were also gifted to young brides as good luck charms and maturing young adults as educational materials, so they did not cater exclusively to the male gaze. Speaking to the widely accepted nature of the graphic images is the fact that they were often created by traditional painters, who were not penalized for their erotic predilections. With titles like “Pillow Book for the Young: All You Need to Know About How the Jeweled Rod Goes in and Out,” there wasn’t much subtlety involved.

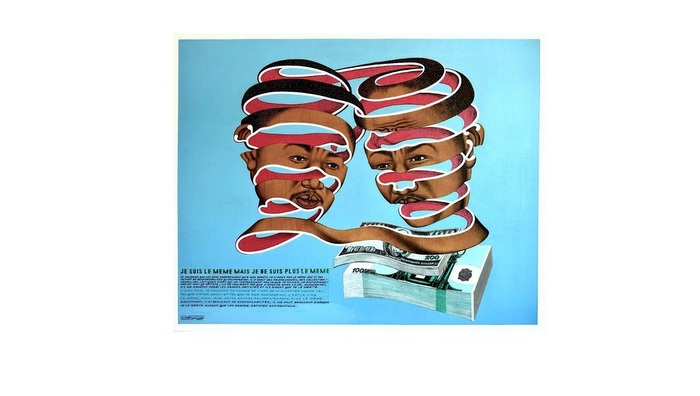

Shunga was banned by the Japanese Shogunate in 1722, but its legacy lives on — and turns on — to this day. Just ask Kio Griffith, the Los Angeles-based curator behind “Neo Japonism: Shunga,” a survey of contemporary artists reinterpreting classic shunga prints. Griffith enlisted artists to have their way with an original shunga print, navigating the space between then and now, copy and original artwork. “It has to be recognizable,” Griffith explained in an interview with The Huffington Post. “But the artists can play, adding their own style, their own humor, and elements relating to modern culture. It’s about putting your ego into it, but allowing it to be truly representational.”

This is the eighth time Griffith has organized such an exhibition, inviting contemporary artists to riff on classical art movements. “There is a long tradition in art history of a student copying the master to get better at their craft,” Griffith said. “It’s not just about copying, but how you work yourself into a composition.”

Griffith himself prioritizes including artists who are just beginning their careers in his shows. “You have to give experience to the artists trying to break into the scene!”

Griffith’s ongoing series of exhibitions, called “Faux Sho,” has previously covered eras including impressionism, expressionism, and symbolism. “At one point I thought, this is all Western art,” Griffith said. “I should branch out to Japonisme.” In 2015, he organized a show inspired by Western artists who were inspired by Japanese art, including Vincent van Gogh and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec.

At first, Griffith mounted the shows mainly in coffee shops, spaces he felt were more accessible than the often insular gallery scene. “I think the general public is a little bit in fear of the white cube,” he said. This iteration, however, takes place at the Japan Foundation in Los Angeles, who invited Griffith to curate a show for the space.

Growing up, Griffith spent half his life in Japan, and was constantly exposed to works of Japanese art. Not surprisingly, the naughty stuff stood out. “It’s startling because of the erotic nature of it, but also, shunga is a higher art form than the traditional woodblock prints in terms of the use of color. A single one can use over 90 woodblock plates. They also really stretch techniques of perspective and flatness. You know that things are enlarged out of proportion but you don’t know what is real — the genitalia, the face, the body, the setting. But when you look at the whole thing it’s very magical and all seems to make sense somehow.”

For “Neo Japonism,” Griffith recruited artists from both Japan and Los Angeles to rework iconic 17th century smut, honoring the works’ identifying features while imbuing them with their own artistic input.

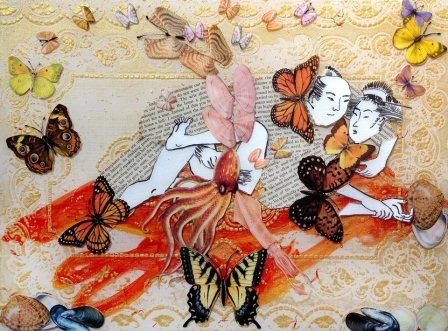

Artists Daphne Hill and Anna Stump transform a Katsukawa Shunsho print into a three-dimensional collage, replacing stark flatness with layers of newspaper, butterflies, gold lace and an artfully placed octopus. The image, a depiction of a master and his servant, is at once feminine and rough, its jagged-edge girliness a contemporary response to shunga’s questionable male aristocratic origins. Artist Ted Meyer recreates Tsukioka Settei’s black-and-white ménage à trois in full color — and adds a special guest. It appears some lucky man is making love to two versions of Yayoi Kusama, one of the world’s most famous living artists, atop a bed of red and white polka dots. Christina Kelly reinterprets “Courtesan and Wealthy Merchant” by Sugimura Jihei, incorporating elements of the California landscape into the backdrop.

“Neo Japonism: Shunga” will be on view until April 23 at the Japan Foundation in Los Angeles. In the meantime, see some of the works on view, juxtaposed with the originals that inspired them.

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com

Related Publications

Leo Pum presents HYPER LIKE at HYPER HOUSE

December 18, 2025

Aargauer Kunsthaus. Klodin Erb. Curtain falls dog calls

December 17, 2025