Work at night is against the day to come. To know the temporal limits of life and shelve sleep is to flout the value of restoration and embrace the elongation of day into the dark, into the wagering time of the nocturnal. The possibility of something to emerge from the dark is a risk to invite enlightening, the uncanny, and the unknown. However, this venture could be for nothing but the verso of these silver thoughts: deterioration and delusion. There is a long history in painting that values the night for what it may promise. From Caravaggio working in darkened sublevel hovels to Rembrandt’s flickering studio lamps, or Joshua Reynolds’ and Goya’s candle-brimmed hats, images of Faustian figures struggling to capture elusive truths in darkness persist into the Romantic era of Eugene Delacroix and Caspar David Friedrich, or their modern counterparts of James McNeill Whistler and Albert Pinkham Ryder; such artists courted the mercurial knowledge of night in their representations of nocturnal subjects and in their habits of painting in the dark.

Against these gamblers was an outlier painter of night that would have nothing to do with such sanguine belief, the German Realist, Adolph Menzel (1815-1905). His raison d’être for night work was without romantic ambitions, but to simply record the night for its special qualities as one would a day. Menzel’s wager was not to hope for secret knowledge, but to use, or perhaps to grieve according to Friedrich Nietzsche, that knowledge which he already possessed, to record an empathy for life and its traces that remain embodied in the material space of a day, before it should fade into shadow.

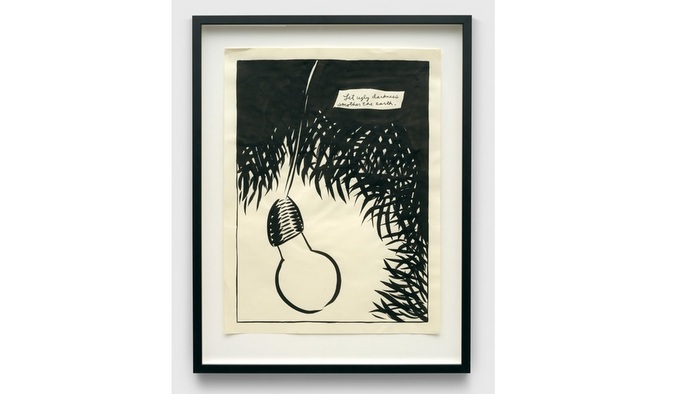

David Schutter’s second exhibition with Rhona Hoffman Gallery contemplates an 1852 nocturnal still life tableau painted by Adolph Menzel, the subject of which was the German artist’s own studio wall in his Berlin home. Thrown into relief by lamplight, Menzel’s wall holds some of the tools of his trade; youthful arms cast in plaster are hung akimbo above the wax cast of a flayed human hand, a skull sits on a shelf in the dark, a palette leans adroitly against the wall. Menzel, in this incredible work, reflects on the persistence of objects that continue to speak beyond the end of day; his studio aid memoires stare back at him in the dark as he attempts to come to terms with the limitations of knowledge, finitude, sight, and skill.

Night Work is a parallel project to the work Schutter produced for his participation in Documenta 14. For that exhibition, the artist made thirty-six drawings after the same numbered Max Liebermann (1847-1935) drawings discovered in the infamous Gurlitt Art Trove in 2012. Menzel was Liebermann’s natural antecedent in the modern German canon. Given Schutter’s exhaustive research methods, he studied both Menzel and Liebermann’s techniques and works at length. Schutter’s own Night Work was, while making the Liebermann work for Documenta 14, moonlighting a kind of B-side response that included his reflections on the studio wall tableau painted by Menzel. For his exhibition with Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Schutter has installed three of his renditions after Menzel’s wall tableau. These paintings are accompanied by a single blind drawing in silverpoint on a prepared ivory ground. Schutter made each work for the exhibition in his Chicago studio from the evening into the night. The same perennial issues that troubled and propelled Menzel as he stared at his wall, are for Schutter, the very foundation of these four spare works.

Related Publications

Museo del Prado | Juan Muñoz. Stories of Art

January 07, 2026

Musée national Picasso-Paris. Raymond Pettibon. Underground

January 06, 2026