It seems mandatory, above all, to refer to the Abela dynasty in Cuba’s art. Eduardo Felix Abela Villareal (1889-1965), one of the founding fathers of our avant-gardism, is on the top of the list. His well-celebrated significance does not hinge solely on the discovery of “The Fool,” the cartoon character that ran through a large chunk of the republican history with his scathing and sharp naivety, but also due to his painting of high esthetic values thematically focused on the national scene: the rednecks, the rumba dancers and other characters that eventually derived in clichés but that at that time turned out to be a sincere and efficient effort to build on the identity of a country that, following the colonial rule period, continued to struggle for becoming a nation.

Eduardo Abela Alonso (1932), the son of the former’s, practiced lyrical abstraction during the 1960s and 70s. However, his work –it’s calling for a critical review– succumbed into oblivion.

Eduardo Miguel Abela Torras (1963), their son and grandson respectively –just Abela in today’s artistic circles– is more than a familiar synthesis; he’s the clear-cut coincidence of the continuity of the legacy, of a heritage he takes on with his signature happiness, jumping into a largely dynamic, ever-changing work that puzzles viewers every once in a while because it permanently seeks its own brand, a way to portray the critical dialogue he engages in with the island nation’s intense reality.1

Abela belongs to a breed of lucid artists, those for whom intuitive representation is not enough –which it is indeed– and who are equally interested in how and why the act of communicating comes through.

He cut his artistic teeth back in the 1980s with a stint in La Aspirina, a satiric supplement of the Tribuna de La Habana newspaper. He also reached out to DDT, a tabloid published by Juventud Rebelde and for many years penciled in as the Mecca of Cuba’s graphic humor. He thought then he’d found his own way. It was a moment of harsh social debates in which boldface names like Manuel, Carlucho and Ajubel, just to name but a few, were efficiently involved in scrutinizing our daily life both in the turf and overseas.

But Abela soon realized he needed more refined tools to express himself in full swing. He had to learn the trade well, and so he commenced studies at the San Alejandro Academy, where he graduated as an engraver in 1991.

When asked who his paradigms were at that time, he never thinks twice to mention the names of Santiago “Chago” Armada and Jesus de Armas, two artists who practiced a different kind of humor marked by great conceptual elaboration and heterodox expressive resources that went beyond the contingency of the joke.2 It was de Armas the first to notice that the young man was steering off the traditional course and suggested him to check on the work of renowned painters, like Picasso and Magritte, for him to pinpoint certain areas in which the so-called “major art” and humor melt into each other in perfect harmony.

At the academy he was taught by Angel Ramirez, who not only provided him with the techniques, but also exerted a tremendous influence on his own vision. Abela likes underscoring the debt of gratitude he has with Ramirez because the work of this master was highly motivational for him –that’s something clearly seen in many of his works.

Later on, at the Cathedral Square Experimental Graphic Workshop, he collided with the works and strong characters of Sandra Ramos, Luis Cabrera, Nelson Dominguez, Zaida del Rio, Roberto Fabelo and Vicente R. Bonachea, watching them in their full creative processes, something which is pretty important in this act of unshackled absorption the formation of each and every artist is characterized by. There, he had the opportunity of rubbing elbows with them all and getting down to work, thinking of himself as someone who was not supposed to recognize barriers or themes or genres. An unlimited universe open to exploration, so full of restless quests and pleasant encounters, popped up before his eyes. It can be surely said that his work and his life had a turning point following his joining TEG. It turned out to be some kind of born-again experience.

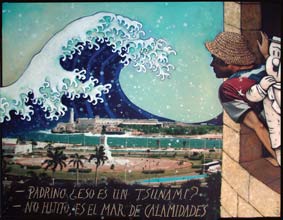

Generically speaking, art reviewers have labeled the thematic and iconic trend seen in our art from the 1990s on as post medievalism. In most cases, it intends to bank on time-primed images that belong to a specific author or not in an effort to stack them up against the convulsed present. To a naked eye, it looks like an escapist strategy piqued by the saturation of a gripping political discourse, yet scarce in terms of formal elaboration. But that’s only to a naked eye. The bottom line is these works share a similar vocation when it comes to interacting with their context in a critical fashion. The point is they appeal to beauty canons which are considered as traditional and that resize themselves through the use of postmodern resources, such as pastiche, parody and, last but not least, legit appropriation.

Generically speaking, art reviewers have labeled the thematic and iconic trend seen in our art from the 1990s on as post medievalism. In most cases, it intends to bank on time-primed images that belong to a specific author or not in an effort to stack them up against the convulsed present. To a naked eye, it looks like an escapist strategy piqued by the saturation of a gripping political discourse, yet scarce in terms of formal elaboration. But that’s only to a naked eye. The bottom line is these works share a similar vocation when it comes to interacting with their context in a critical fashion. The point is they appeal to beauty canons which are considered as traditional and that resize themselves through the use of postmodern resources, such as pastiche, parody and, last but not least, legit appropriation.

Ruben Alpizar, Carlos Guzman, Ernesto Rancaño, Angel Ramirez and Reynerio Tamayo are some of the boldface names that have tried their hand at the also-called neo historicism, a tag like any other that simplifies and vulgarizes a much complex phenomenon. And Abela joined that rank and file, and he did it with good outcomes, especially if we consider that he’s been bound to reinvent himself as a painter. That is, find in his easel, following tiresome sessions, the ways and means that have nothing to do with his basic graphic formation. Because, as a matter of fact, no one can’t mention Goya, Greco or Rubens without métier, that never-ending do good-doing modernity has made all the rage, but without which no deconstruction could be possible.

Hopscotching from one individual exhibit to another, Abela “reveals himself.” He conveys new trails, retreats and findings down a zigzagging pathway, as rigor calls. In Triple A3 he advances his incursion in the 3D world: it’s a set of three large wooden chests created by boxes of the well-known Tropical Island juices, spruced up with homegrown fruits that drift through popular imagination as sexual symbols. That same operation is used again in 11,000 Virgins4 (“La Konga”, a lit balalaika that resemble the Russian lacquers, in which the Virgin of Charity is a matrioska and a couple of drums boasts their snowcaps in the middle of the tropical landscape), Oh My God5 with the piece entitled Hot Line, a retable of Byzantine reminiscences in the shape of a phone booth to get through the “Highest”, while in Kamanutra,6 though in this particular exhibition it jokingly mixes sex and haute cuisine, the object is exclusively shrunk to the quality of the format: trays and sawed wood.

But it’s in Popular Mechanic7 where Abela tosses himself walks the tight rope without safety nets. From my standpoint, here the artist marks the beginning of his coming of age. This is a collection that turns its back on the unpleasing conventional market. However, he starts out from the self-satisfaction of his own inquiries, the ones that ooze out exclusively of the observation process and the remaking of reality he’s been forced to live in. Those are wooden boxes where either scattered objects (objet trouvé) are in or in which graphics, installations or sculptures can be found.

Abela searches into daily absurdity, in the surrealism that shrouds us, those signs of today’s Cuban people, the people who scramble to stand up for a social project based on principles of equity and justice whole endure a tough survival. People who try to get involved in a world in which technology replaces the gods out of their daily hardships. That gives birth to pieces like The Mulattos’ Laptop, a suitcase that includes a keyboard and a screen, plus cleaning accessories, a pitcher, a spoon, a stove, a clean shirt and the image of the Virgin of Charity (a sign on top of the figurine reads “Protection System”), among many other diverse and equally indispensable elements.

Other works mimic websites. Those are the ones the artist attributes to our chores-around-the-house Internet (www.lacuota.com, www.elmani.com, www.lamerienda.com), websites we have to “click on” if you really want to be “in the game”, if you want to “get the knack” of the complex social relationships that are woven out of the singularities of this political and social system. Spectators do not crack up when they stand in front of these artifacts because this is not funny at all. Yet they do flash a reflexive smile as they recognize the piece from their own framework, the one that goes them one better and drags them into a complicated situation in which they must choose between the existential and the predestined individual, full, of course, of symbolic implications.

I strongly believe Abela has definitely jumped into a much bigger fix. The polysemy of his work is open to the spectator’s apprehension ability. No matter how much it looks like, his discourse is indirect. But there’s no harsh criticism or naïve representation whatsoever in it either. In his own particular way of staying awake amidst reality’s gusty winds, and keeping an eye on the weapons he’s been forging along the way, he stands out as a noticeable creator within the vast and very active panorama of Cuba’s art that, as it moves into the 21st century, it’s riddled with questions.

Notes

1 In 1997 the Domingo Padron Art Gallery, in Coral Gables, Florida, organized the Three Eduardo Abela Generations exhibit.

2 This work is based on other sources and a conversation between the author and the artist.

3 La Acacia Art Gallery, Havana, 1998; next to artist Angel Rivero (Andy).

4 CNAP, Havana, 2004.

5 Palacio de Lombillo, Havana, 2005.

6 El Templete Restaurant, Havana, 2008.

7 Villa Manuela Art Gallery, Havana, 2009.

Publicaciones relacionadas