Some time ago I read two interviews with brazilian artist Jose Damasceno. I thought he was an elderly man. I felt like I was “listening” to someone with a lot of experience in life. I was surprised to know that he was born in 1968. His answers brought to my mind Jostein Gaarder’s delicious book Sophie’s World. The Norwegian author speaks about a philosopher from ancient Greece who used to say that to be a good philosopher the only thing we need is to have the “ability to wonder”. And Damasceno, apparently, hasn’t lost that gift, as reflected in his art work.

Some time ago I read two interviews with brazilian artist Jose Damasceno. I thought he was an elderly man. I felt like I was “listening” to someone with a lot of experience in life. I was surprised to know that he was born in 1968. His answers brought to my mind Jostein Gaarder’s delicious book Sophie’s World. The Norwegian author speaks about a philosopher from ancient Greece who used to say that to be a good philosopher the only thing we need is to have the “ability to wonder”. And Damasceno, apparently, hasn’t lost that gift, as reflected in his art work.

Gaarder says that during childhood we all have that gift, and that we start losing it as we get used to the world and grow old. But Damasceno continues to be a child in his heart. Therefore, he philosophizes, although in a particular way. He asks himself questions and tries to formulate the answers… about the universe, the human beings, their relationships; the feelings, the emotions, what is in the antipodes: the macro vs. the micro, the external vs. the internal, the eternal vs. the ephemeral, the order and the chaos, the fragile vs. the resistant, the private and the public… all intermingled, like life events. Maybe that’s the reason why the space becomes a fundamental element in his plastic arts work. Not just for the mere fact of having learned about it though his uncompleted architecture studies.

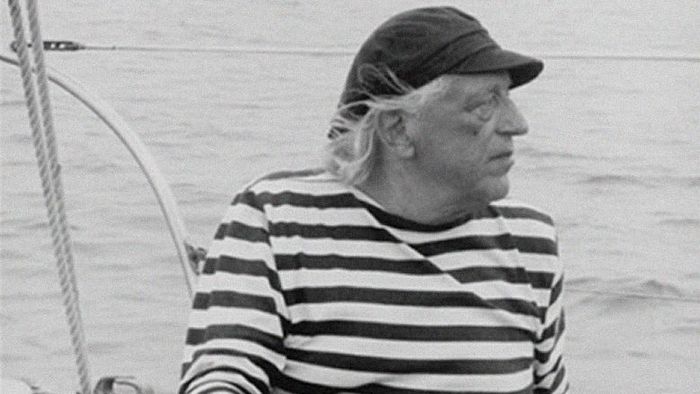

Damasceno is some sort of a “diver” in both the outer and inner space: the physical space, where there are objects, where people’s life takes place; and the space formed by the inner being of the individual, that mysterious “metaphysical” space in the brain, known as spirit and/or soul. He does it with the same curiosity he dived in the ocean of Rio de Janeiro when he was a kid while listening to his breathing and watching the changes in color of the water and the diversity of marine rarities. He described it as “an activity of great concentration, fantasies and adventure.”

The attitude with which he assumes each of his works can be described in the same way. That’s why, even though they are different from each other in terms of “style”, they can be identified by the characteristics previously stated. It seems he wants to bring the public to the same mental state of his. You have to plunge with him into the unusual atmospheres that, since generating so many questions, convince you to join him in his adventure forged out of imagination, energy and subtle humor. Damasceno’s world is more acute, disconcerting and sophisticated every day.

People talk a lot about the globalized world. Fully convinced or not of such assertion. As a consequence, the terms “international music”, “international food”, “international chef” and, of course, “international art”, “international artist” emerged… So, for a work to be considered to be in tune with such circumstances, it has to be made like a kind of “international plate”. It can often be a “recipe” consisting on some grams of minimalism, as much more of conceptualism, seasoned with a few spices taken from the history of art in some of its variants (isms); and of course, you wouldn’t miss putting some technology. Plus, some tribute or quotes of indispensible authors, at least as a snack: Duchamp, Magritte, Beuys… It wouldn’t be a nice plate if it even smelled identity.

People talk a lot about the globalized world. Fully convinced or not of such assertion. As a consequence, the terms “international music”, “international food”, “international chef” and, of course, “international art”, “international artist” emerged… So, for a work to be considered to be in tune with such circumstances, it has to be made like a kind of “international plate”. It can often be a “recipe” consisting on some grams of minimalism, as much more of conceptualism, seasoned with a few spices taken from the history of art in some of its variants (isms); and of course, you wouldn’t miss putting some technology. Plus, some tribute or quotes of indispensible authors, at least as a snack: Duchamp, Magritte, Beuys… It wouldn’t be a nice plate if it even smelled identity.

Within these “international requirements,” that in the end are just a way to sift the grain through the “international market” and through the greedy demands of “international curators”, there are still many artists who don’t even try to have their own “trademark”: some kind of indelible hallmark that gives them personality, character…even some “flavour”, like a good aged wine. Specially, those who respect themselves, who try to have their honesty prevail for themselves and their own works. Tough task, given the circumstances. Damasceno falls into the group of those who maintain the composure.

He has some advantage that speaks out for his honesty. He could be called or feel “international” from his very beginnings, because of the topics he tackles. Since time immemorial, people from all parts of the world, in different epochs, have been asking themselves the same questions: who are we, where do we come from, what is the sense of life, whether there is life after death, or whether God exists, if the space is infinite or not, world and immortal worries.

Damasceno’s artistic career has been consistent with his life. Because throughout it –directly or indirectly– he has focalized those types of concerns that emerged since his early ages, judging by the way he has talked about the games he choose to play, which required the ability to wonder mentioned by Gaarder. And he is still on the search. He still likes to dismantle things, not toys to see what is inside them. Now he seems to want to dismantle formulations built around perpetual topics, plus relativisms.

One of them is people’s concern about time. His work Organization Chart (organograma) is some sort of a “joke” about it. He has been working on versions of this project since 1997. He has conceived it in different means, sometimes on paper, others directly on the wall or as an object. An organization chart is a diagram used to organize tasks, places… Damasceno’s chart uses the words yesterday, today and tomorrow, time sequences through which life develops, supposedly in a linear way; but in his case, they are mixed in a labyrinthine and absurd way. He confuses us and we don’t know where yesterday begins and where tomorrow ends. Where are we today? All of the sudden, we found ourselves thinking about time.

This is another key word in Damasceno’s art: surprise, the same as curiosity. “A permanent curiosity moves me around and encourages me,” he has said. “And it allows me to look for new roads.” And that is why he is so mutable in terms of the shapes, materials and techniques he uses. But, in the same way that cause and effect exist in life, these relations seem to be established among his drawings, installations, sculptures: what gives unity to his work comes from there, in a little bit surreptitious way. Cohesion lies in the concepts he expresses, where he always seem to leave a “clue”, a hint, a trace to follow. It is in the act of thinking about the work, when its density arises.

A density, above all, of poetic associations. He has said: “Our questions, doubts, anxieties, can only find an answered when asked poetically.” Trip to the moon (Viaje a la luna), his installation in the Venice Biennial, 2007, is a good example. As well as Soliloquy (Soliloquio), 1995, part of the collection of the Art Museum of Rio de Janeiro. There is also poetry and humor in Archoptical Slide and Knotptical Slide (a word game in English). He insists here in his views about opposing pairs, where ambivalences intermingle, as well as ambiguities and relativisms of all kind, in this case starting from the dimensions of the objects, the scale.

The Camargo Vilaça gallery hosted an exhibition of Damasceno’s works from 1992 through 1998. In the catalogue, a verse by William Blake introduces the photographic display of the pieces. Its free translation would be something like: “The oak tree, as the lettuce, perish. But its eternal image and its individuality never die, since they return through its seeds; thus, the images made with creativity remain in the seed of contemplative thinking.” Until a little while ago, Damasceno’s studio was just notebooks he carried with him wherever he went to. He has confessed that he may be working on a current work, look at his old notebooks and retake an idea he had formulated before and discover that there is certain connection between them.

Damasceno seems also to turn to memory, to recollections of his past from where he gets some ideas too. With a pool table, some wool and lamps he made Snooker, in 2001, and the piece reminds us of the law of the eternal return, since it brings to our mind the chorals the artist might have seen in his childhood as sea explorer; the same happens with Method for Tracing and Mapping, from 2005. Damasceno continues to dive in the spaces of Rio, detaching himself inside them; he continues to make up images that can remain in those, like him, who still have the gift of contemplative thinking and the mark of individuality.