As I was getting set to broach the new article for this section, an event that struck my attention came to pass. What’s more, it was exciting enough to make me change the subject, or at least put off the article for another issue.

It was no less a report on the national TV’s primetime news in which the anchorman was trumpeting the grand opening in the city of Holguin of the “first exposition ever held in Cuba featuring original artworks by Malaga-born painter Pablo Picasso. The following day, I discovered the piece of news had echoed in the printed press, the Internet, radio stations and even a few international news agencies were beating the drum. Then I realized it had not been a slipup –like the ones we’re so used to– but a major blunder being published and aired by the media time and time again.

I didn’t wait too long to try to correct the media-hyped gaffe. I looked for Pablo (Ruiz) Picasso file. I found it teeming with newspaper clips, recreations and catalogs; a considerable chunk of those documents were published in Cuba, while a few others refer specifically to Picasso’s different exhibits of original artworks held in Cuba. The oldest reference found in the file harks back to 1942, and thanks to a clarifying chronicle penned by Alejo Carpentier and originally put out in the Cuban Gazette in 1962, we can piece together –at least partially– the facts that unfolded during the first exposition of Picasso paintings and gouaches in Havana.

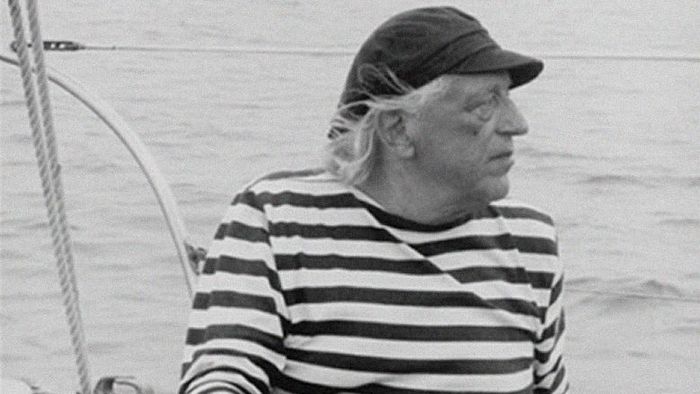

The author writes that Pierre Loeb, a French-Jewish gallery owner, came to this city in early 1942. His baggage included a mysterious roll of cloths and cardboards that he eventually kept safely in his Vedado apartment. At this point in the narration, you don’t need to be a rocket scientist to know what the content was.

The author writes that Pierre Loeb, a French-Jewish gallery owner, came to this city in early 1942. His baggage included a mysterious roll of cloths and cardboards that he eventually kept safely in his Vedado apartment. At this point in the narration, you don’t need to be a rocket scientist to know what the content was.

During the first months of his stay in Havana, Mr. Loeb considered it was impossible to mount a Picasso exhibit in a city peppered with backward criteria on the arts and that was in the middle of an esthetic debate between academicians and modernists. However, little by little Mr. Loeb began to tip his toes into Cuba’s modern painting. When he saw Ponce’s works, he called him the new Watteau, while at the Marianao beaches the paintings of Rafael Moreno swept him off his feet. Then Carpentier notes, that “a spirit of grand merchant was reemerging in him.” Let’s not forget, though, that it was Mr. Loeb who planned and executed Wifredo Lam’s first exhibition in France with the help of Picasso.

Determined to unroll the puzzling cylinder and show the people of Havana the valuable cargo he had brought in –only a handful of people had had the chance to take a peek into it– he accepted to reveal his treasure. It seems that one of the persons in charge of organizing the exposition was Carpentier himself, who at the same time chips in some valuable historical information in his chronicle. Carpentier himself ordered the printing of a red-and-black billboard at the well-known Ucar Garcia y Cia. press to promote the exhibit. We are also told that he counted on a superb graphic reporter for the occasion: Jose Manuel Acosta.

The three-week exposition was mounted at the Lyceum & Lawn Tennis Club in Havana back in June 1942. I can imagine the surprise of the spectators as they feasted eyes on the work of the Malaga-born genius. Most of them reacted admirably, though a few had grotesque attitudes, like the man who shouted: “I want the Greek beauty back.” Or the shrink who visited the exhibit each day in an effort to unravel some features of schizophrenia or paranoia in Picasso’s paintings.

At the end of his chronicle, Carpentier wondered whatever happened to the paintings. Chances are some of them were shipped back to France by Mr. Loeb himself; others were acquired by the few collectors who lived in Havana at the time, like Costa Rican painter and diplomat Max Jimenez. The fact of the matter is there are no traces of those paintings exhibited in Cuba in 1942. But in 1945, critic Jose Gomez Sicre planned The Immobile Exhibition at the Lyceum that included a piece made by Picasso and entitled Skull of Sheep and Grapes, mentioned in Carpentier’s 1962 article. So, there’s no doubt that was one of the paintings from that memorable exposition that had been photographed by Jose Manuel Acosta.

Nearly 70 years have gone by since then, and this is not a chapter from one of Carpentier’s novels, but rather something that did occur and many scholars can bear out.

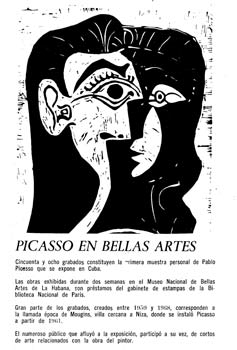

Thirty years after the 1942 exhibit, the National Museum showcased a set of Picasso engravings in 1972, all of them hailing from Printing Cabinet at the National Library of France. As a curiosity and a way to prove how history repeats itself, we found a brief blurb in the Cuba magazine that announced the mounting of the first Picasso originals in Cuba. To top it all off, just another blunder leaked out in a similar blurb published in the Granma newspaper, this time around informing about the exhibition of Picasso works “to mark the artist’s centennial birthday,” right when the painter was still alive. He passed away a year later at age 91.

In both 1981 and 1985, the National Museum presented two exhibitions with Picasso artworks. The first one was called Picasso: Original Works, and it did take place to mark the artist’s 100th birthday. The sample embraced a vast period of his creative lifetime, somewhere between 1930 and 1971, depicting different engraving techniques. The second one was entitled Bullfighting, in clear reference to the like-name series made by Picasso in 1958. It consisted of 59 phototypes, a facsimile edition of the originals with a printout of 260 copies.

At this point, we let the research open for other archivists who’d like to delve into the topic of Picasso exhibitions in Cuba. For example, it would be very interesting to look into Picasso’s first exhibition in Latin America, Mr. Loeb’s stays in Havana and his relation with the Cuban art between 1942 and 1945.

Hopefully that “first exposition of Picasso originals in Cuba” announcement won’t happen again… ever.