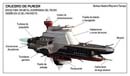

One of the most striking and symbolic artworks of the past Havana Biennia was no doubt “The Oil Tanker” by artists Reynerio Tamayo (Niquero, 1968) and Eulises Niebla (Matanzas, 1963). The piece intends to mull over some of the globalization facts: the squabble among the great superpowers, the way transnational corporations gobble up Third World nations and the ever-growing ecological disasters sweeping the world.

The black gold has been the main cause of the latest warring conflicts and its price rules the world market. The “tanker” resembles the slithering shape of a snake that strengthens the use of curve and dynamic lines, ending in a perfect finish, something that shows the masterfulness of the authors of this complex piece, based on its size (23 feet long) and the materials used by them.

We know Reynerio Tamayo very well. A first glimpse puts anyone immediately in his pictorial world, first of all because his images stand for the long and winding road the history of art has been marked by. His paintings carry that appropriating and deconstructive character of part of today’s Cuban art. But in the case of this particular author, those modulations and dialogues are perfectly ingrained in an incorporative esthetics that dissolves all influences and comes up with a perspective of his own, where no marks from any school or tradition are visible anymore, but just the artist’s personality. In that kind of art, he’s made room for European classical paintings, together with those from avant-gardism, pop, comic, Japanese engraving, all of them conforming a symbiotic game in which epochs and styles are nixed to offer us party of imagination and a very accurate interpretation of Cuba’s own world and its contemporary life.

His leap to a volumetric piece could come as a surprise for many, but truth is Tamayo engaged in a process of nonstop evolution. He’s a very restless artist who sets out to tell us –through all the means he can lay hands on– that rich world of imagination. He’s tried his hand at all kinds of materials and his preference for sculptures goes back to his years as a college student. One of his first volumetric pieces seen by the Cuban public was “The Gods’ Journey to Endlessness” that belonged to a collective exhibition entitled Ways to Flash a Smiles within the framework of the Eighth Havana Biennial. Built with the help of Pol Chaviano, this artwork consisted of seven pieces, each formed by a token nave attached to an orisha of the Yoruba pantheon.

During the Ninth Biennial, he took everybody aback with “Taxi-Shark”, a piece with tremendous meaningfulness that was not placed on a privileged spot because its space-challenging size required a city street rather than a gallery hall. And one of the “refrigerators”, together with Ruben Alpizar, that made up the collateral exhibit “User’s Manual” at the National Center for Monumental Conservation, Restoration and Sculpturing (CENCREM).

Eulises Niebla, from the Higher Art Institute’s class of 1989 and author of a vast collection of works in the turf, is penciled in as one of the most prize-winning artists of the past decade. He’s taken part in both collective and individual expositions, and his sculptures –highly recognized on the island nation and overseas– are scattered in different parts of the country, especially in Havana’s Vedado area.

For the author of a generally non-figurative work, his pieces are yet marked by stunning spirituality and fully harmonious, well-integrated compositions. His materials of choice are metal, marble, cement and glass, either single or combined. Another recurrent sign of his poetry is linkage of meanings and the opposite dialogue, the challenging handling of heavy, humongous metals to express aerodynamic lines related to the mankind’s challenges and the codes of modernity. His initial works stem from the concept of environmental sculpture as they engage in sort of a conversation with both the environment and the passersby. Modernity in Niebla is deduced from the conceptual meaningfulness of his works and from the modern framework they are inserted in.

This oil tanker is their first joint work. They already did a few variations of the “The Wonder Lamp” during an individual exhibit staged by Reynerio Tamayo and entitled Magma Mia!!!, at the Villa Manuela Gallery, run by the Cuban League of Writers and Artists (UNEAC).

Collaboration among these artists has accrued over the last year and they’re already piecing together their first personal exhibition at the UNEAC Gallery –a locale that in recent years has become– one of the most active and influential spots linked to the nation’s visual arts. This exhibit is a continuation of a collective project to be held at the Havana Gallery between May and June 2010. The project consists of a collective watercolor exposition –not watercolors as such, but rather as pieces that act as previous ideas out of 3D artistic proposals.

Back to their first individual exhibition, it’s important to point out that the works will address warfare and its repercussion in the attitude of people. Battleships, modern weaponry, armored vehicles put together in a symbiosis of objects and machinery used in daily life. Thus, we’ll watch armored baby carriages, armored cruise liners, the well-known submarine lamps, guns replacing people. All this much is owed to the constant warring conflicts and dog-eat-dog violence among men, and they come storming into our households by the hand of the unstoppable outreach of mass media.

“Nautilus Lamp” is the opening piece in the exhibition, serving as some kind of linkage between the ongoing event and the Magma Mia!!! Expo. But this time around, they get a hold on Captain Nemo’s famous submarine forged into the wonder lamp; the end result is a new fish-shaped armored battleship. It’s a highly esthetic and conceptual piece featuring delicate movements and the kind of crooked lines fund in the lamp –used only to smooth the armored structure. It’s by far the most delicate, subtle and poetic piece of all those on display.

The “Leisure Cruise Liner” piece portrays a set of terms and meanings. On the one hand, the attractive services these deluxe vessels offer to tourists with their interesting voyages around the world. It shows a unique and different form of tourism, with an identity as a symbol of relaxation, exclusiveness, entertainment and quality. However, the cruise liner looks more like an armored and heavily armed destroyer, just like a battleship. It’s a stunning structure tethered to the ceiling, like a warning about the vessels of the future and the threat of uncertainty.

A school bus –usually used to transport children and teenagers to and from school– designed to protect students with small windows, hefty metal structures and a multitude of safety add-ons. In this case, the object has been transformed into an armored vehicle ready to launch an attack. Under the original title “School Bus”, the piece warns us about the ongoing developments that keep society utterly distraught and at the brink of a pit of unchangeable disorders. It thus shows us the dark side of the human race.

“Baby carriage” is the most trespassing piece in the show. Under the outer structure of a baby carriage, a number of sharp spears, cannons and heavy metal elements jut out, assailing spectators visually. This provocative and huge piece makes reference to war conflicts, violence and power violations.

The creators are no strangers to the universal phenomenon war stands for, and they even fly in the face of the current state of developments mankind is going through. Even though we must still wait to see these works on display, we can rest assured that this new stage of joint efforts between both artists will surely touch and amaze the public, with valuable outcomes for those who love smart and exquisitely executed artworks. Thus, we’ll have the chance to see these two outstanding creators of today’s Cuban fine arts.

As Tamayo himself has put it, “I work with Eulises because he’s my friend. He’s a sculptor and I’m a painter. We share ideas and there are things he can do as a sculptor and I can’t. It’s a nice experience. I like this four-handed endeavor.”

September 2009

Previous publication Preserving The Caribbean’s Modern Architecture*

Next publication Octavio Paz and art review

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022

Giovanni Duarte and an orchestra capable of everything

August 26, 2020