Why is Warhol more present than Beuys? Why do both facesof the same coin illustrate the exchange process experimented by different notions such as essence and appearance? “Green Car in Flames I” (1963) is Warhol’s most valued artwork to the date: 71,17 million dollars in 2007. But his art became as enigmatic as his life. Andy was never married and didn’t have children. He wasn’t even interested in adopting abandoned children so he could take his iceberg pop make-up off in front of them. That’s the reason why there were no lawsuits regarding his inheritance. The Warhol who painted portraits of bankers, art dealers and millionaires got his ambition fulfilled: a lot of money has been invested in order to ensure his immortality.

Beuys became famous due to different things he did: in Aachen he turned an aggression into a prophetic/religious event, he participated in the requiem for a domesticated mouse that had just died (“Isolation Unit”) along with North American performer Terry Fox, in 1970, and he explained the meaning of his drawings to a dead hare while holding it in his arms. He also talked to bees and deer. His extravagances brought about anti-glamour shock effects. Why did he refuse to see the city that snatched the hegemony of modern art from Paris? Let’s remember that in 1974 he travelled to New York on a stretcher with his face covered, so he was taken on an ambulance to René BlockGallery where he had the coyote action. After the event, he left in the same way he arrived.

Beuys became famous due to different things he did: in Aachen he turned an aggression into a prophetic/religious event, he participated in the requiem for a domesticated mouse that had just died (“Isolation Unit”) along with North American performer Terry Fox, in 1970, and he explained the meaning of his drawings to a dead hare while holding it in his arms. He also talked to bees and deer. His extravagances brought about anti-glamour shock effects. Why did he refuse to see the city that snatched the hegemony of modern art from Paris? Let’s remember that in 1974 he travelled to New York on a stretcher with his face covered, so he was taken on an ambulance to René BlockGallery where he had the coyote action. After the event, he left in the same way he arrived.

“I believe that this hare can achieve more victories for the world’s political development than a human being. I’d like to elevate the status of animals to human beings”. (Joseph Beuys)

The impact of Beuys’ attitudes wasn’t designed to attract headlines on the tabloids. It was a conceptual dramatic character not to be gotten through among the art showbiz people. Even his performance eccentricities contain an agonic background that compels the liberating exorcism. The essence of his socio-political project has nothing to do with that mixing of superficiality, selfishness and financial speculation present in the artistic world. Working with the means of art and not for the advertising media represented a radical position he never quit. This Warholian concession guaranteed his mass media resurrection.

In the vortex of his questioning poetry, Beuys intents to fulminate those who impose a severe tutelage with the hindrance of his silence: “Duchamp doesn’t deserve attention or critic. He must be considered just as what he is, an object of art sited in the museum. My artworks, far from it, are tools that promote debate and discussion”. The expanded concept of art, as perennial motive of discussion, avoids Duchampian vision of creative act, where artists go from the intention to the realization through a chain of totally subjective reactions. According to Duchamp, there is an emptiness that is expressed as an arithmetic relation between what is thought, but not expressed and what is involuntarily expressed.

Beuys refuses Marcel Duchamp without mentioning Picasso playing the role of symbolic antagonist. Just as Warhol, the guru who belonged to the Hitlerian youth “admits without stating” that the creator of “The Great Glass” represents the anti-bourgeois per excellence. The “we can all use a urinary” that emanates from the “Fountain”(1917) by Marcel, finds its translation in the “we can all be artists” borrowed by Joseph from his compatriot painter and engraver Alberto Durero (1471-1528). Less dreamer and more ironic, Warhol proposed: “We can all drink Coca-Cola. From a whore to the president of the United States.” A phrase that takes off just as the chorus of a song created to be repeated by hypnotized people who face the trick of equality.

When lashing the overvaluation of Duchampian silence, Beuys released the plague of Teutonic ego. An ideal relief to exhibit that arrogance apparently impugned by humble Marcel as the fatal vice of artists. On the contrary, Warhol maintains serenity. He recognizes that Duchamp and Greta Garbo or B-rated movies deeply marked him. While dismissing radical positions, he dazzles with the frivolity of sarcasm: “Buying is more American than thinking and I’m the height of American”. From his relationship with Pablo Picasso, Andy only remembers an absolute truth: “Paloma” (the name of the famous painter and sculptor’s wife).

For many observers, the triad Duchamp-Warhol-Beuys is the core axis of most of the contemporary art created in the last decades. However, the voluntary retirement of Duchamp as top responsible of the artistic uprising from the 20th century isn’t interesting for people who take the piece of gossip as merchandise over rumor as idea. An important reason for business artist to prevail over ethnographer artist. The significance of political activists such as Martha Rosler, Krysztof Wodiczko or Guerilla Girls in the history of conceptual art is not decisive for people who take refuge in the banality of Gaston Bachelard’s sentence: “Images are stronger than ideas themselves”.

Less people miss conceptualists such as Hans Haacke, Daniel Buren or Chris Burden who were interested in processing ideas without following the comfortable option of selling. Nowadays, any visual producer (important or not) yearns for and can even make a life from the artistic-commercial mechanism. Even in third world countries with precarious dynamic of state or alternative market, there is always a collector or buyer from a cultural institution ready to acquire creations that have nothing to do with the retinal massage.

Sanctifying Warhol underestimating Beuys has become a habit. What’s indisputable is that Andy Warhol is more alive than ever. You just need to glance through mainstream influential art magazines to check the devaluation suffered by Joseph Beuys’ myth-poetic legacy. The romantic sermon on ethical commitment loses strength due to its uselessness in the context of global product. Andy’s cold aura as pop emblem replaces the warmth as anthropological residue emerging from the materials and tools manipulated by Joseph during his interventions.

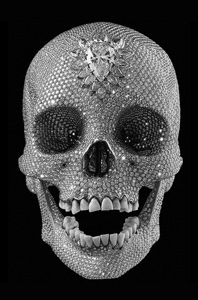

Damien Hirst (Bristol, 1965) represents a strategic hybrid of Duchamp-Warhol-Beuys trilogy. If some people think that Beuys is the hard-essence and Warhol the soft-appearance, Damien tries to be Beuysian in appearance and Warholian in essence. He seeks to merge the opposite accomplices and dissolve them into a malleable archetype related to these times. With his astronomic sales of animals embalmed through the complicity of sculptural recipient and science, Hirst symbolizes the anti-romantic who believes that art is also about money and this one is very important (or urgent) for life.

Damien Hirst (Bristol, 1965) represents a strategic hybrid of Duchamp-Warhol-Beuys trilogy. If some people think that Beuys is the hard-essence and Warhol the soft-appearance, Damien tries to be Beuysian in appearance and Warholian in essence. He seeks to merge the opposite accomplices and dissolve them into a malleable archetype related to these times. With his astronomic sales of animals embalmed through the complicity of sculptural recipient and science, Hirst symbolizes the anti-romantic who believes that art is also about money and this one is very important (or urgent) for life.

Would it be possible to rebuff such as devastating evidence?

In a reflection on the intense romance between art and money, critic and curator Massimiliano Gioni expresses: “It doesn’t matter if artists flirt with money or completely prostitute themselves, because the fine art can take us to other places, in the very instant when it immerses itself into the present”. The fact is that Hirst’s series of sculptures, installations and paintings descend to the deep immediacy of a process described by art historian Michael Baxandall in the following terms: Artworks are deposits of social experience, and as such “fossils of our economic life”.

The career of the former young British art is read as a serial novel. Damien Hirst is the credit next to the formo showcase with a dead shark inside. “Death’s physical impossibility in someone else’s living mind” (1991) is the suggestive title of the key work created by the artist who discovered in the right time by advertising magnate and collector Charles Saatchi. Shrewdness that worked as opportune and legitimating exchange between the individual who signs the artwork and the art dealer who handpicks it and promotes it by using media power.

Hirst conquered such economic position in the 1990s that he repurchased the artworks he sold to the one that discovered him. The lawsuit started in 2001 due to the way the artworks were exhibited in a London gallery, owned by Saatchi. According to a press release published by a newspaper in Madrid: “The artist wanted his showcases-cells with fragments and stuffed bodies of animals to be exhibited in large spaces without works of other sculptors around”.

Damien crystallized the dream of every producer: “recovering without touching” the fetish-testimony of his fight to gain fame and, of course, a vanity banquette was offered as a challenge to that man who “only recognizes art with his wallet” named Charles Saatchi. On the other hand, I was very encouraging to see the emergence of a man that was capable of publicly challenging the terminator of authorized critical voices.

As for the only artwork he couldn’t take away from his former promoter, Hirst has said: “I believe that the shark represents that old Victorian idea regarding to you attracting the world instead of you going after it”. Such statement counts on a convincing philosophical simplicity. Who wouldn’t be charmed by the aggressive beauty of a tiger shark that is no longer dangerous? What about the 12 million dollars offered by collector Steve Cohen (owner of SAC Capital Advisors in Greenwich, Connecticut) to restore it when it was auctioned by Saatchi in 2004?

Between frivolous and anthropologic, this business artist who was obsessed with death embodies an illusion of the crowd: admiring the distraction of a mortal that obtains whatever he wants without uncommon physical and intellectual efforts. An ecstatic fan would swear that taking a nap in a scatological limbo is the prelude for the metamorphosis in which the ribs of a sheep become bills.

The consumption of high scale horrifying visualization allows a proposal such as Hirst’s to gain the attention of critics and the public as he is the most powerful living artist in the world and, at the same time, personifying that contemporary notion of “unputrid eternity” in which auctions and fairs play a leading role. So, every event around him becomes a piece of new. Once, the gallery’s cleaning lady swept away one of Hirst’s installations because she thought that those were wastes from the inaugural vernisagge. This so pre-produced and blatant move was London BBC the day after.

Again, the absurd validity of that Warhol’s statement which, in that time, was taken as another sensationalist phrase of the man who became the “medium” of mass media: “Evil doesn’t exist; good is where the press says it is”.

Early this year, artist Michael Landy created “Art Bin” project. He installed a transparent deposit at South London Gallery, which was turned into an art bin. To do it, he called famous and unknown artists so they donate artworks considered failures. So sculptures by Tracey Emin, Gary Hume’s oil paintings or a self-portrait of legendary Peter Blake ended up at the municipal dumping site.

Damien Hirst couldn’t miss Landy’s show, so he delivered two paintings of skulls created by his assistants. As it’s obvious, there’s a close tie between trash and this aesthetic hierarchy destroyer who declared while the donations were dumped: “Nothing is good enough so it can’t be there”.

Against the persistence of affectations, art merges with life in an almost brutal way. The fear of failure and illusion of stepping on the red carpet dazzle the most lucid critics in the new millennium. Perhaps without chasing that goal, Duchamp established the expression of provoking as the solution for the communion between art and market. Nobody can imagine how many impostors from different spots in the universe take advantage of his prank-wild card that deleted the bounds between art and non-art, to offer the visual production an air that can be turned into asphyxia.

Against the persistence of affectations, art merges with life in an almost brutal way. The fear of failure and illusion of stepping on the red carpet dazzle the most lucid critics in the new millennium. Perhaps without chasing that goal, Duchamp established the expression of provoking as the solution for the communion between art and market. Nobody can imagine how many impostors from different spots in the universe take advantage of his prank-wild card that deleted the bounds between art and non-art, to offer the visual production an air that can be turned into asphyxia.

It’s true that Beuys showed the cracks of a post-war fragmented into traditions in order to separate art and life, from positions linked to an institutional paralysis. Now, what’s the meaning of social fine arts’ humanist implications, when facing the indifference of those who underestimate as authentic economic values the formula in which “CAPITAL” is not money but the product of capacity? The gift to confuse is more than a strategic skill. Perhaps, that’s why Beuys never tried to cause laugh and clung to the dilemma of the (his) story as definitive way out.

There is no larger mystery in Warhol’s life than the cause of his death in 1987 due to wrong vesicle operation. That was how journalists finalized the fact: “Was he into AIDS? Was it a fortuitous mistake at New York Hospital?” Some people said that it might have been an assassination related to a new boutade that could invalidate the cost of his work. Finally, the chameleon of five hundred wigs and one view retakes the immortality as the nightmare of the dream he tried to build.

The death of Beuys, one year before Andy’s, due to a heart failure didn’t catch the mass media interest. The piece of news got drowned along with the three bronze jars that were dropped to the North Sea containing his ashes. A ritual to be saved in the silent memory of time.

The art as experience translated into fallacy is solved in a formula that includes material and spirit, price and value, numbers and metaphors. Through different ways, Beuys and Warhol perpetuate the aura of their legend at the expense of art as spiritual redemption or prosperous business. Beyond commercial incidences, their positions illustrate a crucial Duchampian axiom: “The artist must be a work of art”. Andy got this statement to highlight the spirit of personality cult as habitual artistic support at The Factory: “We are flesh and bone works of art”. From their peculiar attitudes, Warhol and Beuys are present in the pages of Art News and the academies of contemporary art.

“The work is worth a lump sum” (Damien Hirst)

Damien Hirst acts as his own intermediary, without taking the vital impulse that might give legitimacy to the false truthfulness of his lies. The sales agent and his Big Factory, so sought-after and beaten by the critic, set a dramatic distancing that is impossible to compare with the spectacular Marina Abramovic, Orlan or Stelarc. Being a representative phenomenon of a visual production that conquers the market doesn’t entails deserving the grade of symptom in the nomenclature of artistic processes.

Hirst’s visual offer satisfies a real demand, where the work is the mean and the career its purpose. Ad when we say “work”, the category might result in questionable fictions that are ready to fill a huge empty space. Without resulting in soft neopop as his predecessor Jeff Koons, Damien already fulfilled the Warholian chimera of being a business artist. That’s the reason why one of his colleagues from Sensation describes him “not as a genius of art, but genius of marketing”. His incrusted-with-diamond platinum skull was sold to an investment group for 75 million euro.

Could the hope of leveling or exceeding a negotiation in which the word art succumbs in the mind of a living person?

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022

Giovanni Duarte and an orchestra capable of everything

August 26, 2020