(A Pioneer Exhibition of a Movement of Intuitive Artists)

Sometimes certain historical and cultural processesare preceded by elements, that although do not constitute notable events, allow us to perceive the significance they will achieved shortly after. It’s necessary to analyze and evaluate these phenomena when rebuilding the connections and interconnections that have shaped the history of Caribbean art, as well as the time to know the names of those who are behind the great history of the evolution of art in the region. It will be required to link the creative experience with the systems that govern its exhibition and consumption, understanding the artistic production as a complex cultural phenomenon, linked to a given audience and certain political and cultural conditions.

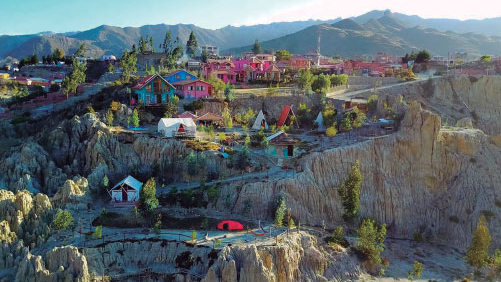

While searching in Jose Veigas files, I found a document, in a box containing the information of the exhibitions in 1976, something that might be considered an example of what I mentioned before. The catalog shows an exhibition that took place in Havana in May. “Eight Self-taught Jamaican Painters” curated by David Boxer. The publication, with a red design, contains several cards in which can be seen a photograph of each artist on one side, and a brief biography on the other. Along with the catalog there are three press releases that are proof of the positive response of the critic. Cino Colina, journalist from Granma newspaper wrote about the exceptional nature of an exhibition that brought together 39 works from eight Jamaican artists, while quoting Boxer`s words, who a year earlier was appointed director of the Young National Gallery of Jamaica, founded in 1972, saying that the exhibition of the work of primitive artists was an interesting fact, due to the fact that the Cuban Revolution devoted to the development of the people. Along with Colina’s note, a small note issued by the National Council of Culture announcing the postponement of the inauguration, which corroborated the invitation letter included in the same folder. Finally, a longer text, three and a half pages, shows the significance of intuitive art, and deepens into the work of each one of the artists.

While searching in Jose Veigas files, I found a document, in a box containing the information of the exhibitions in 1976, something that might be considered an example of what I mentioned before. The catalog shows an exhibition that took place in Havana in May. “Eight Self-taught Jamaican Painters” curated by David Boxer. The publication, with a red design, contains several cards in which can be seen a photograph of each artist on one side, and a brief biography on the other. Along with the catalog there are three press releases that are proof of the positive response of the critic. Cino Colina, journalist from Granma newspaper wrote about the exceptional nature of an exhibition that brought together 39 works from eight Jamaican artists, while quoting Boxer`s words, who a year earlier was appointed director of the Young National Gallery of Jamaica, founded in 1972, saying that the exhibition of the work of primitive artists was an interesting fact, due to the fact that the Cuban Revolution devoted to the development of the people. Along with Colina’s note, a small note issued by the National Council of Culture announcing the postponement of the inauguration, which corroborated the invitation letter included in the same folder. Finally, a longer text, three and a half pages, shows the significance of intuitive art, and deepens into the work of each one of the artists.

Far from building an isolated fact, there is a curiosity; the exhibition and its catalog became points of reference to understand a significant part of the future of the art in the Caribbean region. In a date, that may be considered early, in a context that may be considered unusual, the exhibition became a turning point of a process that concentrated the elements of the relation between the artist and the museum, the artistic education, the function of the curators, or between the artistic discourse and the historic and social opportunities of the region.

In fact, some events have more significance at the time of facing the analysis made to the exhibition. In first place, reflexes the cultural impact of Michael Manley´s government and his will to take his social agenda to the Jamaican foreign relations level. Boxer´s word talk about a close relation between the Cuban revolutionary government and the Jamaican one, in the diplomatic and the cultural fields. “Eight Self-taught Jamaican Painters” was the counterpart of the Cuban art exhibition that took place in Jamaica earlier, which represented a milestone in the cultural relations between both countries.[i]

Secondly it is obligatory to reflect about the exhibition presented in Jamaica, three years after, in August 1979, “The Intuitive Eye”, also cured by Boxer. It paved the way to the construction of the Jamaican art. “The Intuitive Eye”, proposed a new idea to the art called “primitive”, applied to all the Caribbean area, and at the same time represented a Boxer´s proposal to claim for a part of the Jamaican art that was pushed to the background. The “primitive” art not only began to be considered part of the history of national art, but to the national culture due to its values. From 1979 the intuitive began to be part of the national artistic cannon in a process that was not free from certain contradictions. Quoting Veerle Poupeye:[ii]

The notion of Intuitive art is therefore best understood as a canon that holds a special and highly contested position in the broader artistic and cultural canons that are being negotiated in Jamaica and not just as a politically correct synonym for Primitive, Naïve, or Outsider. [...] The status of the Intuitive artists thus remains ambivalent, located in a no-man’s land between high and low culture, in which they are not empowered to take control of their representation which remains dependent on the artistic establishment.[iii]

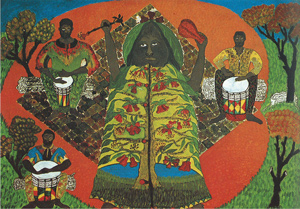

However, in the intuitive art, a concept that substituted “primitive art” or “naive art”, would be found the values that represented the national culture of Jamaica; the strength of Christianity and of the Rastafarian movement, the impression of the revolts that led to the independence of the island, the Pan-Africanism or the importance of the authenticity and the personal search as a creativity factor. That relation between the Jamaican history and the creative processes has to be taken into account at the time of conceiving what intuitive phenomenon assumed. So, from the first time the definition of what is an intuitive artist represents a problem. An intuitive artist is the one who lacks of artistic formation, the one that is self-taught. However, the concept goes beyond, including a strong ideological point of view.

These artists paint, or sculpt, intuitively. They are not guided by fashion. Their vision is pure and sincere, untarnished by art theories and philosophies, principles and movements. They are for the most part, self-taught. Their visions (and many are true visionaries) as released through paint or wood, are unmediated expressions of their individual relationships with the world around them –and the worlds within. Some of them– Kapo, Everald Brown, William Joseph in particular –reveal as well a capacity for reaching into the depths of the subconscious to rekindle century old traditions and to pluck out images as elemental and vital as those of their African fathers.[iv]

From the very beginning there is in the analysis and in the exhibition of Intuitive art an interest in binding such art demonstration with a positive consideration, with an image that exceeded the one of the primitive artist. It may be said the intuitive art was born, at least as a movement associated to the need to define what an intuitive artist is, as well as the movement to integrate national arts body.

The fact the decision of bringing to an exhibition in which the Jamaican art is represented by the artists that later became part of “The Intuitive Eye” represents a real declaration of the intensions, an indicator of the guidelines that would take shape years later: of the eight names on self-taught painters Eight ... a total of seven; Clinton Brown, Everald Brown, Sam Elisha Brown, Sidney McLaren, Roy Reid, Mallica Reynolds “Kapo”, and Gaston Tabois. They took part in the exhibition of 1979.[v] That made evident Boxer’s belief to vindicate the intuitive, promoting a position that eliminates the boundaries between popular art and academic art, establishing an open look at the framing of modern art in the Caribbean region.

Searching in file becomes, at this point, an obligatory method when compiling a critical genealogy of the creative processes of the region and the positions of the people involved in those. The document becomes a witness of the events and platform from which discourses and trends are shaped that just by contrasting criticism may be located in their historical and cultural context. “Eight Self-taught Artists from Jamaica” states in this regard, not only the impression of the popular of Jamaican and Caribbean art at that time, but the expression of the direct claim of a purely Caribbean artistic modernity.

[i] The exhibition has its precedent in a painting exhibition at Sociedad Lyceum in Havana in November 1952.

[ii] Veerle Poupeye (2007): “Intuitive Art as Canon”, en Small Axe, 24, pp. 79-80.

[iii] Thus, alluding to diverse perspectives and contexts, authors like Petrina Dacres, Andrea Douglas, Annie Paul, Kim Robinson or Veerle Poupeye have theorized on the matter, broaching the analysis of the public art, the institutional system, the editorial phenomenon or the art review. See David Boxer and Veerle Poupeye (1998): Modern Jamaican Art, Kingston, Ian Randle Publishers; Petrina Dacres (2009): “But Bogle Was a Bold Man: Vision, History, and Power for a New Jamaica”, en Small Axe, 28, pages 112-134; Petrina Dacres (2004): “Monument and Meaning”, Small Axe, 16, pages 137-153; Andrea N. Douglas (2004): “Facing the Nation: Art History and Art Criticism in the Jamaican Context”, en Small Axe 8 (2), 49-60; Kim Robinson (1991): “New Art Galleries”, in the Jamaica Journal, 24 (1), pages 38-49; Annie Paul (1997): “Pirates or Parrots? A Critical Perspective on the Visual Arts in Jamaica”, in Small Axe 1, 49-65; Veerle Poupeye: (1992) “Voix et visions: les arts plastiques en Jamaique”, in Pierre Bocquet (Ed.) 1492-1992. Un nouveau regard sur les Caraïbes, París, Creolarts, pages 109-120.

[iv] David Boxer (1979): The Intuitive Eye, National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston, p. 2.

[v] Hailing from different generations, artists included in Eight Self-Taught Artists from Jamaica will play a key role in the following decade, the one after ours, with their works generating an array of reviews and, in some cases like Everald Brown or Kapo, a good deal of retrospective exhibits.

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022

Giovanni Duarte and an orchestra capable of everything

August 26, 2020