By Sarah Cascone

The 11th Gwangju Biennale is a thinking man’s biennial. For a start, the exhibition’s title, “The Eighth Climate (What Does Art Do?),” is drawn from a theory of 12th-century Persian mystic and philosopher Sohravardi, later expanded by 20th-century French philosopher Henry Corbin, that beyond the physical realm lies an “eighth climate” that one can reach through the power of imagination.

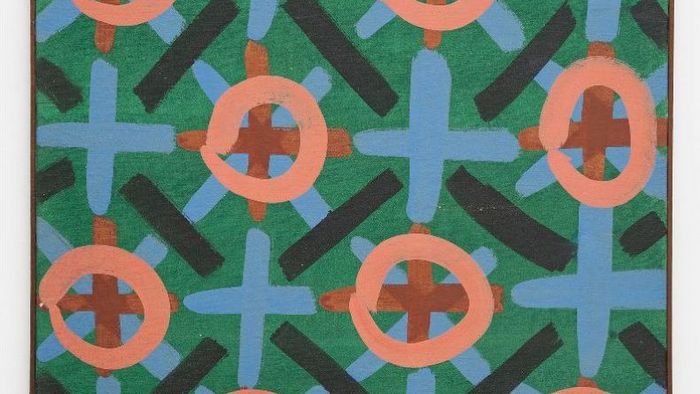

This idea allows such diverse work as Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian‘s mirrored mosaics, abstract cotton pieces by Mika Tajima, Trevor Paglan’s government surveillance-inspired artworks, and Marie-Louise Ekman’s cheeky illustrations, to comfortably coexist.

“The way that they [Sohravardi and Corbin] imagined this zone is really similar to the way contemporary art is operating,” explained artistic director Maria Lind, director of Stockholm’s Tensta Konsthall, in a press conference on September 1. “Each artwork has its reverberations depending on where, when and how it is presented.”

In other words, art “functions a bit like a seismograph,” Lind added, noting that it is capable of “detecting things before they become apparent to other parts of society.”

Along with curator Binna Choi; assistant curators Azar Mahmoudian, Margarida Mendes, and Michelle Wong; and curatorial collective Mite-Ugro, Lind has selected 252 works by 101 artists, displayed at the main exhibition hall and nine other sites scattered across the city. (When queried about her selection of an all-female curatorial team, Lee had a simple explanation, insisting she chose them “because they are the best and woman are the future.”)

They’ve put together a show that is full of intriguing pieces, but is somewhat lacking in flashy, Instagram-baiting works. “I am not particularly interested in spectacle for the sake of spectacle,” Lind admitted. “If I engage with it, it has to be smarter than normal spectacle.”

This is an admirable goal, but is somewhat undercut by the curious curatorial decision to eschew all explanatory wall text. The labels list only the artist name and the title, and require the use of your smart phone, and the app for QR codes for any additional info—as if we need more reason to look at our phones.

This forced reliance on technology does viewers a disservice. The Gwangju Biennial does a wonderful job of bringing together an eclectic group of artists, many of whom I was encountering for the first time. For instance, among participating Korean artists is Inseon Park, a Gwangju native, who creates haunting, dystopian-style paintings based on run-down buildings, construction, and development in her hometown. This array of unfamiliar work was exciting, but without traditional wall text I was left with an undeniable sense of frustration.

Walid Raad’s collaboration with Suha Traboulsi, a row of packing crates with rough paintings on one side, has the advantage of built in explanatory text on one of the boxes. The work is Traboulsi’s recreation of paintings he made during his tenure as the chief registrar of public collections in Lebanon. When that country’s planned Museum of Modern Art failed to open in 1975, the many works acquired for the collection were gradually appropriated by government officials. Traboulsi’s work on the empty crates served as an important record of the missing art.

I was immediately drawn to Tommy Støckel’s Gwangju Rocks, colorful geometric forms made of paper, but it was only during Lind’s tour of the exhibition that I learned that the artist actually set up shop in the city to make the work. The handcrafted sculptures are based on 3-D scans of rocks that serve as markers and signs right here in Gwangju, one of many instances where Lind arranged for participating artists to work in and with the local community.

Visually captivating were a selection of colorful, large-scale photographic prints by Faivovich and Goldberg. I was even more intrigued once Lind told us that they were actually microscopic images of slices of meteorites.

The exhibition’s centerpiece lies near the entrance, beyond a colorful metal curtain of chains by Ruth Buchanan. A large bookstore loaded with donations from around the world, the installation is Spanish artist’s Dora Garcia reconstruction of the Nokdu bookstore, which was an important gathering place during the Gwangju Uprising in May 1980, where nearly 250,000 people stood against the military regime.

Upstairs, another standout work is Michael Beutler’s Daein Sausage Shop, almost a room unto itself. The bricks, or “sausages,” that make up the walls are formed from recycling-bound paper and fruit netting from Gwangju’s Daein Market, made locally with a wooden machine designed by the artist.

Across the way, Lind has created a thoughtful gallery revolving around light-based art, all displayed in a darkened room. Her goal was to “try to create an environment where we can watch video without being isolated in black boxes like we’re used to,” she explained. The result sees a set of sculptures by Amalia Ulman happily cohabit with projected and video works.

During the press preview, a few artists were still placing the finishing touches on their installations. artnet News spoke briefly to Nadia Belerique as she carefully walked across her piece Have You Seen This Man, creating footprints with photosensitive emulsion on a long carpet. “It actually exposes over time to leave a print,” she explained, noting that she had used several different pairs of shoes to suggest a variety of characters.

Our quick chat offered the kind of insight into the work that I craved throughout the exhibition. A work can have power and presence based solely on its visual qualities, but a viewer shouldn’t have to jump through technological hoops to get more information about it.

The 11th Gwangju Biennale, “The Eighth Climate (What Does Art Do?),” is on view at the Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall and various sites throughout the city, September 2–November 6, 2016.

Source:news.artnet.com

Related Publications

Apply now to Swab Barcelona

April 22, 2024

Waldemar Cordeiro: La Biennale di Venezia

April 16, 2024