In this complex and contradictory beginning of the 21st century, we are forced to live in a world of immediate, unexpected and unusual events. Doubtlessly, the attack against the WTC towers in 2001 turned out to be a tragic forecast of the drama that would characterize these initial decades, caused by both social contradictions and natural catastrophes. Currently, there are millions of inhabitants on the planet hit by the hard living conditions created by the economic crisis generated in the developed countries. Abruptly, the messianic projects, the pharaonic works were brought to a standstill, as well as the utopia of the indefinite welfare promised by neoliberalism’s empty dynamics, interrupted without prior warning when the financial speculation and the real state bubble exploded in the United States and in Europe. Despite the consumer internationalism and the fantasy of the globalized world based on the media equipment accessible to the individual experience, it is evident that there is a tendency to the fragmentation of political and social initiatives; and paradoxically, an introversion of the cultural expression, more devoted to the individual introspection and the dialogue with the immanence of everyday reality than to the concretion of ambitious collective projects.

Art and literature do not stand aloof from the world economic crisis. That is why in recent international events emphasis is made on artworks and authors removed from mercantilism and from the presence of the jet set stars, in search of artistic expressions from both local communities and from proposals aimed at solving the pressing problems of the humblest strata of the population, in particular in the countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America. It is not by chance that this year, the curators’ proposed objectives coincided at the 30th São Paulo Biennale –Venezuelan Luis Pérez-Oramas (1960)- and at the 13th Venice Biennale of Architecture –English David Chipperfield (1953)-; the first one dedicated to the Imminence of Poetics, and the second one to the Common Ground. On the one hand, the work of 112 artists was presented, estranged from traditional commercial circuits and identified with innovative initiatives; on the other hand, it was evident the need of an architecture removed from formal exhibitionism and defined by the current demands of sustainability and economy.

In the show concept offered by the most important art biennials, a particular prominence was generally granted to grandiloquent discourses and to the craftsmen of grand narratives. Pérez-Oramas accepted the hard challenge of integrating into the renovating dynamics that characterized recent São Paulo Biennales: the 28th one, directed by Ivo Mesquita, called the “biennale of the void” for leaving one floor of the building free, turned out to be a denunciation of the crisis in current art; the 29th one, organized by Moacir dos Anjos and Agnaldo Farías –There is always a glass of sea for man to sail-, took in radical political attitudes. When facing denunciations and proclamations, Pérez-Oramas opted for documenting the existence of divergent personal paths, distant from nationalist positions, political enunciations, or from unitary artistic movements, in the attempt to dismantle traditional objective discourses.

In the show concept offered by the most important art biennials, a particular prominence was generally granted to grandiloquent discourses and to the craftsmen of grand narratives. Pérez-Oramas accepted the hard challenge of integrating into the renovating dynamics that characterized recent São Paulo Biennales: the 28th one, directed by Ivo Mesquita, called the “biennale of the void” for leaving one floor of the building free, turned out to be a denunciation of the crisis in current art; the 29th one, organized by Moacir dos Anjos and Agnaldo Farías –There is always a glass of sea for man to sail-, took in radical political attitudes. When facing denunciations and proclamations, Pérez-Oramas opted for documenting the existence of divergent personal paths, distant from nationalist positions, political enunciations, or from unitary artistic movements, in the attempt to dismantle traditional objective discourses.

In comparison with previous editions, where an important space was assigned to the visitations of distinguished groups of artists of international renown, from the eternal Picasso and Wilfredo Lam to the current dislocations of Francis Alÿs and Ai Weiwei, in the 30th edition of the São Paulo Biennale we find minimalist and introverted discourses by artists with little spread works. It is a Biennale characterized by the presence of infinite voices that are present in our contemporary Babel; and lacking an specific theme, more identified with a “motive”, an agglutinating pretext for the multiple questions that current artistic practice arouses –in its poetic, expressive, discursive, expository, vocal decisions- and the mental and intuitive process of each author, “in the gray uncertainties of existence, in the archipelagic weightiness of life”. To present artists who believe in the live letter, in the active memory, in the shades, in the traces and in the body as a unique heritage for creation. It is about a polyphonic Biennale structured in different conceptual units, such as “survivals, alter-forms, drifts, voices”, that facilitate the dialogue, the confrontation and the analogical reading of the works presented.

Pérez-Oramas –director of the MoMa’s Collection of Latin American Art in New York- and his team made a titanic effort to gather this considerable group of young authors –a great deal of them are little known and come from different parts of the world, with the notable absence of Cuba-, trying to overcome the administrative and economic difficulties that historically characterized the Biennale Foundation. If we had to identify this show, we would define it as a low profile one, due to its lack of shrillness and frights.

At the “Piranesian” Palácio das Indústrias designed by Oscar Niemeyer in 1952 at the Ibirapuera Park, architects Martin Corullon and Gustavo Cedroni established a serious and coherent exhibition system based on small spaces defined by white panels totally separated and independent from the facades and structural elements, organizing different circuits with a free-flowing and continuous circulation. In face of the hegemony of the media and audiovisual presentations, a good deal of care was taken of spacing them out to avoid the shrillness of sounds and images. A small group of artists were granted the privilege of extensive spaces: the film showings by Canadian Guy Maddin (1956), that interpreted scenes from Hollywood silent movies; the unusual accumulation of objects by Brazilian Arthur Bispo do Rosário (1911-1989); the obsessive television images by German F. Kriwet (1942); the humorous interpretations of technological objects by American Dave Hullfish Bailey (1963); and the imaginative habitable cells by Israeli Absalon (1964-1993). A small homage was also paid to Italo-Brazilian artist Waldemar Cordeiro (1925-1973), reproducing his child labyrinth outside the building.

At the “Piranesian” Palácio das Indústrias designed by Oscar Niemeyer in 1952 at the Ibirapuera Park, architects Martin Corullon and Gustavo Cedroni established a serious and coherent exhibition system based on small spaces defined by white panels totally separated and independent from the facades and structural elements, organizing different circuits with a free-flowing and continuous circulation. In face of the hegemony of the media and audiovisual presentations, a good deal of care was taken of spacing them out to avoid the shrillness of sounds and images. A small group of artists were granted the privilege of extensive spaces: the film showings by Canadian Guy Maddin (1956), that interpreted scenes from Hollywood silent movies; the unusual accumulation of objects by Brazilian Arthur Bispo do Rosário (1911-1989); the obsessive television images by German F. Kriwet (1942); the humorous interpretations of technological objects by American Dave Hullfish Bailey (1963); and the imaginative habitable cells by Israeli Absalon (1964-1993). A small homage was also paid to Italo-Brazilian artist Waldemar Cordeiro (1925-1973), reproducing his child labyrinth outside the building.

The thematic distribution of the artworks among the three large levels of the building contributes to the fluent reading of this 30th Biennale. The direct access floors –the ground floor and the basement- are set aside for majestic gestures, with extensive artworks that appropriate the physical space and capture the spectator’s attention: great video showings, and installations of media artifacts, all showing particular and intimist visions, solitary reconstructions of reality. This exhibition area also offers the spectator greater possibilities of interaction and integration, through obsessive videos about the contradictions of daily life and work –Argentinian Martin Legon (1978) and Turkish Ali Katzma (1971)-, and the performance games proposed by Franz Erhard Walther (1939).

The second floor proposes –among other diverse options- several enjoyable rereadings of the Duchampian ready-mades, seasoned with the recreation of the classic-postmodern universe according to Charles Jenks’ viewpoint.

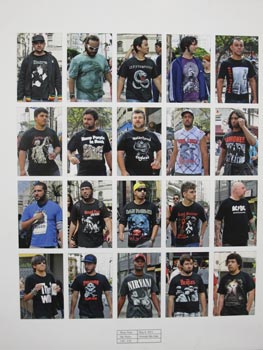

Already on the third and last floor, the exhibition of the poetics of that which is transient and insignificant is shown in the photographic series that portray the intimate moments and eternize the memory of the daily life that goes unnoticed given the implacable weight of immediacy. These obsessive records mark the culture of instantaneity, and qualify the transmutation of the imminence of the stare, into the immanence of the poetics exhibited. The serial work by Dutch Hans Eijkelboom (1949) states the infinite variations and possibilities of the human race in the big metropolises, while American Mark Morrisroe (1959-1989) captures what is casual and intimate in the life of the others. Following the guidelines of the voyeur, Brazilian Alair Gomes (1971) makes up a whole visual alphabet with the wonderful images of young athletes on the road of Copacabana. Clearly referring to the erotic series by Robert Mapplethorpe, Alair structures a visual composition that reminds of the notes in a musical score.

If “in the beginning was the Word”, the printed letter has a particular presence in the Biennale. In the current predominance of images over words, it is about recovering the ekphrasis, the link between word and image; and being also “the imminence an expecting attitude; it is about expecting words from images; and expecting images from words”. Letter and words appear with different interpretations, from the recovery of memory through the daily record of a diary, to the link with Dadá’s aesthetic experience of using words as a plastic composition; or recovering the value of voluminous dictionaries and encyclopedias, almost abandoned by their substitutes on the Internet, according to the vision by Uruguayan Alejandro Cesarco (1975) and Brazilian Odires Mlászho (1960); or when putting the poetic word before architectural creation, as it is applied in Ciudad Abierta (Open City) in Valparaíso. Multiplicity of uses for the words that appear in the work by Robert Smithson (1938-1973); Moyra Davey (1958), Marcelo Coutinho (1968), Hugo Canoilas (1977), Bernardo Ortiz (1972), among others.

If “in the beginning was the Word”, the printed letter has a particular presence in the Biennale. In the current predominance of images over words, it is about recovering the ekphrasis, the link between word and image; and being also “the imminence an expecting attitude; it is about expecting words from images; and expecting images from words”. Letter and words appear with different interpretations, from the recovery of memory through the daily record of a diary, to the link with Dadá’s aesthetic experience of using words as a plastic composition; or recovering the value of voluminous dictionaries and encyclopedias, almost abandoned by their substitutes on the Internet, according to the vision by Uruguayan Alejandro Cesarco (1975) and Brazilian Odires Mlászho (1960); or when putting the poetic word before architectural creation, as it is applied in Ciudad Abierta (Open City) in Valparaíso. Multiplicity of uses for the words that appear in the work by Robert Smithson (1938-1973); Moyra Davey (1958), Marcelo Coutinho (1968), Hugo Canoilas (1977), Bernardo Ortiz (1972), among others.

Subconscious and memory play a fundamental role in the artistic message. There is an objective and programmed assimilation of the real world, but at the same time experiences that do not go through reason are chosen, they stay in the subconscious and remain registered on memory. It is about passing on a vision of the environment experienced through multiple registers, from the unforeseeable and erratic dynamics of autistic teenagers recorded by Fernand Deligny (1913-1996), to the memory records chosen from the accumulation of photographic images. They are the serialized plates by Horst Ademeit (1937-2010); the portraits of common people gathered by August Sander (1876 -1964), and the mortuary masks of David Moreno’s (1957). To that it can be added the valorization of everyday objects that assume symbolic and almost surrealist meanings in the work by Nino Casi (1969) and Hans-Peter Feldman (1941); and in the imaginative presence of the local culture in the pencil drawings by Chilean Sandra Vásquez de la Horra (1941). Lastly, the cultural memory appears in the transposition of the classical heritage in the work by Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925-2006) and by Savvas Christoduolides (1961).

The end of the tour holds for the spectator pieces in which the personal vision of the artist is stated in a much more aggressive and fiercely personal manner, offering approaches focused on the particular universes of every human being. An example of it being the work by Tehching Hsieh (1950) –an artist born in Taiwan that currently lives in the United States-, who develops performance works in which he puts his iron will to the test, true challenges that last throughout a year, in an obsessive repetition and ruthless comment on the well-known alienation of the human being in the industrial society. In contrast to that, there appears the naivety and the naïf world of marginal cultures not yet contaminated by the hypothetical scientific advances of modernity: it is the freshness of the pictographic cosmogony by Fréderic Bruly Bouabré (1923), born in the Ivory Coast. Maybe he is the one who makes us suppose –to paraphrase Robert Filliou (1927-1987)-, that in the end, life in its complexity can be more interesting than art.

Río de Janeiro, October 2012