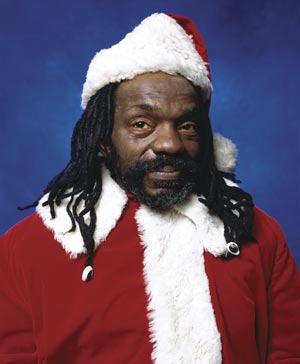

As if he had just left a Jimi Hendrix concert, I saw Andrés Serrano turn up in Terminal 2 at José Martí International Airport in Havana. His figure is after all a late modern appropriation of the countercultural movement his generation grew up in. In his face, he carries the mixture of races that have modeled the ethnographic landscape of this country. That is why I felt him close: his phonetics is like ours, although he lacks the richness and diversity of words Spanish has and behind its musicality the Anglo-American accent is left; something perfectly understandable in a man born and educated in New York. His mother, originally from Key West, lived her first years of her childhood and youth in Cuba until she returned to the United States in 1947. His father, of Honduran origin, was of Chinese descent. Hence the polyethnic constitution he inherited.

Andrés Serrano was invited to participate at the Eleventh Havana Biennale. He exhibited at the Fototeca de Cuba (Cuban Photographic Library) ten images that attempted a little journey along a good deal of his works. This artist, who studied at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, does not like to be considered a photographer because in fact, his academic learning was closer to painting. To identify himself with a certain technique or expression is not something that pleases him: for him, art only exists in its conceptual expression. He acknowledges the influence Marcel Duchamp, Luis Buñuel, and Federico Fellini had on his career. From Duchamp, he takes the freedom to understand the object and to turn what is implausible into a work strategy. From Buñuel and Fellini, he learned to show life’s reverse and obverse, and to explore human mind’s obsessions without restrictions.

The voice of Andrés Serrano begins to gather strength in the mid eighties. Since that time, he has not left his Mamiya camera of Japanese manufacture, and he is still in love with traditional printing. His relation with the artwork is cerebral and intuitive. He never manages to know in detail the expressions of the people he photographs because he is immersed in the adjustments he makes to the composition. His photographic studio is not sophisticated; he can be in interiors or transport himself to the rhythm of uncertainty in any street. He has not only experimented with the usual materials for development in the lab, since he also considers his bodily fluids to be working materials. What interests him is making tangential cuts to life and showing sincerity. Letting it all flow through the lens and out of it. He does not get tired of saying his pieces are what the eye meets, with neither malice aforethought nor premeditation.

Joseph Beuys saw in Fluxus actions an easy way to shock the bourgeois; that is why his strategy was to look for a more anthropological level in art, by studying the material’s phenomenological possibility to evoke metaphors. The works by Andrés Serrano, though he plays with the forms of appearance and simplicity, continue to create opposing scenes and linguistic superimpositions between the teaching pretensions of the artist and they are received. Controversy does not constitute a starting point; it is restored from its way of apprehending the world and the evident fissures between what is and what should be. Andrés knows vision processes are not precisely those of reality, nor they constitute a way to assume understanding.

In Nietzsche’s work titled The Birth of Tragedy, the philosopher commented on the counterpoints of modern culture between the Dionysian and the Apollonian worlds, a conflict that has continuously gone along with the course of art in recent years. In his artworks, Serrano has followed those parameters. The binary discourse does not remain as a simple enunciation; it is marked by violence and the subtleties of difference. This creator preserves the baroque spirit. His pieces are thought “big”, they aspire to become gigantic tryouts of what they show. His motivation is to set out to definitiveness. That is the spirit in series like Nomads, The Klan, Immersions and many others. In each of them, sacredness and paganism converge. Early works like The Scream (1986), Crucifix (1983), Cow’s Head /(1984), Heaven and Hell (1984), Dread (1984) or Locked Brains (1985) are the antecedents of all that would come afterwards. Serrano alters the liturgical rules of Christian faith to enter into a more carnal experience of sacrifice. Pleasure and pain are shown to us as complements of desire. Myth is divested of artifice in order to make it coexist in an environment of great Neo-expressionist sordidness. Behind some of these scenes, we find Caravaggio’s light, Durero’s graceful environment, Goya’s mystery, or Brueghel’s or Bosco’s apocalyptic sense. Many artworks created afterwards, like The Passions by Bill Viola, owe lots to these premonitory pieces.

In Nietzsche’s work titled The Birth of Tragedy, the philosopher commented on the counterpoints of modern culture between the Dionysian and the Apollonian worlds, a conflict that has continuously gone along with the course of art in recent years. In his artworks, Serrano has followed those parameters. The binary discourse does not remain as a simple enunciation; it is marked by violence and the subtleties of difference. This creator preserves the baroque spirit. His pieces are thought “big”, they aspire to become gigantic tryouts of what they show. His motivation is to set out to definitiveness. That is the spirit in series like Nomads, The Klan, Immersions and many others. In each of them, sacredness and paganism converge. Early works like The Scream (1986), Crucifix (1983), Cow’s Head /(1984), Heaven and Hell (1984), Dread (1984) or Locked Brains (1985) are the antecedents of all that would come afterwards. Serrano alters the liturgical rules of Christian faith to enter into a more carnal experience of sacrifice. Pleasure and pain are shown to us as complements of desire. Myth is divested of artifice in order to make it coexist in an environment of great Neo-expressionist sordidness. Behind some of these scenes, we find Caravaggio’s light, Durero’s graceful environment, Goya’s mystery, or Brueghel’s or Bosco’s apocalyptic sense. Many artworks created afterwards, like The Passions by Bill Viola, owe lots to these premonitory pieces.

Blood seen through Cow’s Heador the hanged dog in The Scream, from the early eighties, are undoubtedly antecedents of the pieces that later made up The Morgue (the most renowned pieces from the series were made in 1992). Broken Bottle Murder (1992) is a human head with a slit throat. Its landscape is terrifying and the image manages to apprehend itself as a whole inside a great close up. The cadence of movement is felt in a suspension that goes in and out of the picture with absolute freedom. This artwork, although made on the photographic medium, goes beyond any formal-type pigeonhole. It is neither documentary nor fictional. Serrano relativizes the way to understand genres and makes a brutal analysis of our classical ideal of beauty.

When we observe Saturno devorando a su hijo (Saturn Devouring His Son) by Goya, few people question the aggressiveness of the scene. However, maybe photography has that punctum Roland Barthes saw, of a time that is and will no longer be, because it preserves the best evidence of reality above any possibility that lie facilitates. Perhaps the essence of these works is in rebelling against the restrictions that are generally imposed on this medium, expecting it to be the reflection of a deceitful moral order. Every day, the so-called training cinema, and the way in which imaginaries are handled within videogames, appeal more and more to the most ruthless stimulus of violence.

When we observe Saturno devorando a su hijo (Saturn Devouring His Son) by Goya, few people question the aggressiveness of the scene. However, maybe photography has that punctum Roland Barthes saw, of a time that is and will no longer be, because it preserves the best evidence of reality above any possibility that lie facilitates. Perhaps the essence of these works is in rebelling against the restrictions that are generally imposed on this medium, expecting it to be the reflection of a deceitful moral order. Every day, the so-called training cinema, and the way in which imaginaries are handled within videogames, appeal more and more to the most ruthless stimulus of violence.

Amongst the pieces that belong to the The Morgue series, we find Pneumonia Death, Death Unknown or Child Abuse, which call upon us to think about the true splits between life and death. The energy of those characters makes us feel them alive. Andrés shows the fragility of life and we are thrown into a story that can be invested with chance and accident. Cause and effect dissolve in a same category: the coherence established among all work stages of this creator is not gratuitous.

The history of art, so linked to the history of religions, has been marked by the fear death provokes. The whole ideal of transcendence of the Western thinking is set on that basis. To culturally dismantle attitudes like these is also questioning the very own genealogy of a kind of epistemology already established in the annals of civilization. Serrano leads us to the essence of Zen Buddhism, while he establishes that nothing is permanent.

Another one of the most interesting chapters of Andrés’ career path is the series Immersions, which includes one of the artworks that made him transcend: I am referring to Piss Christ (1987), a piece censored by the renowned Republican Senator Jesse Helms. Although the conceptual making of this photo is exceptional, the political attacks from extreme right positions in the United States opened up an assured road to success for him: the prices rocketed and collectors felt it was time to buy from an artist that disturbed certain powerful sectors. However, the piece, as all his works, did not intend to attack the Vatican, nor the essence of Catholic religion.

In a recent conversation we had, I told Andrés I had read the Vatican wanted to take part in the Venice Biennale with its own pavilion. He told me without hesitation that he was willing to convince the people responsible for this action that he could be one of the artists in their supposed list.

In Piss Christ, Serrano uses again the crucifixion as the central theme; only this time, within the traditional chemistry of the photographic developing process, he included urine. His main motivation was experimenting. For this creator, restrictions do not exist; art only makes sense if there is a will to rethink everything. In 1912, Picasso “destroys” for the first time the pictorial surface: materiality did not use just painting in itself anymore when a rope was introduced around an oval image which had in its center a patch of oilcloth with a chair-cane design pasted onto the canvas of the piece. Collage was thus inaugurated. Shortly afterwards, in 1913, Duchamp showed the world his first readymade with the bicycle wheel.

Andrés is indebted to that spirit of renewal, which is why he introduces new working methods that give a conceptual load to his works. The transformation goes beyond the use of the lens to capture psychologies or environments, or beyond the way in which emulsion is handled or the enlarger operated. This time, the developing material carries the biological records of the artist. The artworks that appear in Immersions belong to Christian and pagan mythology; every one of them stays in the half-light or the chiaroscuro effects provoked by the white and black contrasts with evident traces of the urine’s acidity impregnated on the photographic material sides. From this stage are White Pope and his Red Pope, iconoclastic point of reference of what Maurizio Cattelan would do in 1999 with his celebrated and polemical La Nona Ora (The Ninth Hour).

Immersions is the indisputable starting point of a later artwork titled Body Fluids, in which he resorts again to Marcel Duchamp’s works and to his definition of eroticism as the basis of any kind of understanding of human sensitivity. It is well-known the turbulent relationship between the founding master of Dadaism and the Brazilian poet and sculptor Maria Martins, to whom in 1946 he gave the Box in a Valise deluxe edition XII, as a testimony of that passionate sexuality. The original artwork this set treasured was the rarity of a drawing shaped as an amoeba. For years, no one could understand its meaning. Finally, it was shown at a chemistry lab in an FBI office in Los Angeles, where they found out that the reddish paint with a satiny finish was mixed with semen.

Immersions is the indisputable starting point of a later artwork titled Body Fluids, in which he resorts again to Marcel Duchamp’s works and to his definition of eroticism as the basis of any kind of understanding of human sensitivity. It is well-known the turbulent relationship between the founding master of Dadaism and the Brazilian poet and sculptor Maria Martins, to whom in 1946 he gave the Box in a Valise deluxe edition XII, as a testimony of that passionate sexuality. The original artwork this set treasured was the rarity of a drawing shaped as an amoeba. For years, no one could understand its meaning. Finally, it was shown at a chemistry lab in an FBI office in Los Angeles, where they found out that the reddish paint with a satiny finish was mixed with semen.

Body Fluidsis a special project within Andrés Serrano’s creative path. Perhaps the most performatic artwork he had made until then. The readings of the body go from being social to being individual, until they get to the suggestion and synthesis of any somatic reference in a mixture of minimalism and visual stridency. Milk, blood in all its forms, and semen start to be the materials in the palette of an artist who conceals himself in photography as a sort of “transmedium” or “metamedium” to come out then as a conceptualist that bets on the hedonism of classical painting. The most puerile themes or the most scatological discourse turn out converted. There is a reinstatement of beauty in the delicacy of forms, from an abstraction that manages to get rid of any anecdote to take us to pure sensitivity. The apparent ambiguity of these artworks does not manage to dissociate itself from the social appearance that goes with the artist, which we perceive when we observe Semen and Blood III (1990) or Blood (1987). In many of these works, Andrés incorporates the ludic element: Untitled (Ejaculate in Trajectory XIV, 1989) is the attempt of capturing photographically the external course of an ejaculation. According to what the artist himself has told, it was hard for him to synchronize the camera’s self-timer while concentrating in the act of masturbating himself; programming the machine for a minute, he would only manage to freeze-frame after 19 or 20 seconds. These pieces are undoubtedly closer to performatic intentions than to a formal search in the printed results. Although they don’t fail to reveal a neat finish, we understand them more as works documenting an omitted action than as works presenting something visually nice that obviates in its first approach the very same act that gave birth to them.

Death, blood, and fluids –as I noted before- do not fail to go along with a creator that lives in the instant of an obsessive who does not want to let anything escape. The September 11 events made him meditate. History did not end, it started again. Hence the series America and another artwork that appears as part of the 9-11-01 titled Blood on the Flag (2001). That is how the artist saw the collapse of the towers. Bloodstreams left their abstract structures to slide along the American flag. It is succinctly reflected in the genesis of a tragedy. This piece is also an implicit message to Duchamp, who in 1943 was commissioned by Vogue magazine to make its cover that should have supposedly been a homage to the first President of the United States on the anniversary of his birth; and in which Washington’s profile, turned 90º, symbolized the map of the United States. The set was made with red-dyed gauze. The artwork generated polemic among the magazine editors because the material used alluded to sanitary towels, thus creating an analogy between the bloody gauzes and the flag, something difficult to explain in a context of patriotic exacerbation as a consequence of what was happening during the Second World War.

The photographs that make up the series A History of Sex are from the mid nineties. Andrés Serrano has said in countless occasions he was not interested in doing the history of sexuality, his intention had been to show a history of sexuality. This series, which started as a personal project, received the sponsorship from a Dutch museum afterwards. It is no coincidence that power and sex have been concomitants in his inquiries. As Michel Foucault, he is motivated by the scrutiny of control paradoxes and the reins that move the standardization of the truth at any imaginary’s level.

In these images, the artist questions the hypocrisy with which all these themes are seen in the United States, and recalls the scandal provoked a few years ago when Janet Jackson’s breast was “carelessly” exposed at a concert. He contrasted thus the simulation at the social level with the height of the sex industry through the Internet. Again the artist puts on the table the prejudices of castration and the asceticism demanded to art and which is not consistent with reality. Andrés presents and represents scenes of a virulent gruesomeness that have crossed his mind; because he is convinced they are also in the minds of many others. This conviction makes him doubt the fragile borderline that differentiates art from porno. Then, he jokingly says the distinction may lie in the bit more expensive production that art entails. In Helene (1996), Master of Pain, Leo’s Fantasy (1996) or Antonio and Urike (1996), he alters meanings through the way in which he presents the order of things. Serrano subverts the classic naturalness of a sex shop in any capital in the world for the museum or the gallery. From there, he shows us what is unrepresentable with the suspiciousness of the “cursed man” whose intention is to make us accomplices to what is seemingly false and forbidden.

In these images, the artist questions the hypocrisy with which all these themes are seen in the United States, and recalls the scandal provoked a few years ago when Janet Jackson’s breast was “carelessly” exposed at a concert. He contrasted thus the simulation at the social level with the height of the sex industry through the Internet. Again the artist puts on the table the prejudices of castration and the asceticism demanded to art and which is not consistent with reality. Andrés presents and represents scenes of a virulent gruesomeness that have crossed his mind; because he is convinced they are also in the minds of many others. This conviction makes him doubt the fragile borderline that differentiates art from porno. Then, he jokingly says the distinction may lie in the bit more expensive production that art entails. In Helene (1996), Master of Pain, Leo’s Fantasy (1996) or Antonio and Urike (1996), he alters meanings through the way in which he presents the order of things. Serrano subverts the classic naturalness of a sex shop in any capital in the world for the museum or the gallery. From there, he shows us what is unrepresentable with the suspiciousness of the “cursed man” whose intention is to make us accomplices to what is seemingly false and forbidden.

Andrés Serrano’s expectant eye does not get tired of finding. His objective is neither looking for a direct political denunciation nor revealing a demagogical answer. He prefers to observe, and he likes us to approach many of his proposals with a certain air of defamiliarization. So it happened with the series Klan. This fundamentalist group, Ku Klux Klan, had not being a point of reference for art so far. However, behind this detached representation, the internal contradictions in the United States are revealed. Against the tolerance towards racial ghettos in New York or San Francisco, we find the segregationist policy in states like Georgia and Arizona. It is not fortuitous either the choice of working with the Klan. Andrés comes from a Latin family; he is a man of mixed races and has felt the effects of racial discrimination. Nevertheless, he does not deny his interest in making inquiries in the interstices about who hides behind the hoods. One of the pieces that attracted me most in this tryout was Klanswoman (Grand Kaliff II, 1990), in which the camera lens creates a counterpoint with the feminine eye enclosed by the immensity of the white color that borders the black background. Question, tenderness, femininity close up in a symbol marked by essentialisms.

It is curious that in the year 1990, the seriesThe Klan and Nomads coincide. They are like two sides of the same coin. By juxtaposing two occurrences society “does not want to see”, Serrano generates a microutopia. He is quite certain it is not in his hands to change the life of people who “have nothing”, of “losers”, but he knows that from the art he can help “ennobling them”, and he reverts the logic of representation and its epic matrix. He is aware of the bipolarity generated by the production, circulation, and consumption of the work of art. People with high economic status begin to collect photos of people that are alien to them and who express hushed up situations. The titles of every one of the pictures are the real names of those characters that begin to destabilize the family tableaus of those who decided to buy one of these printings. Many are the anecdotes Andrés has regarding these pieces: on one occasion, I heard him say he took great pleasure in hanging the portraits of the homeless at the Castle of Rivoli in Italy, because they looked like kings, which proves that for this creator, the site and the history of the place where his pieces are located are part of the profit for what he does. The recipient becomes part of an event in which the look is inverted to reach those areas of existence that cannot go unnoticed. Andrés’ work and his attitude in carrying it out with the nomads, takes us back to the experience lived by Edward Curtis and his photographs of North American Indians at the turn of 20th century.

For Andrés Serrano, as for many, the events of September 11th, the collapse of the Twin Towers, marked a milestone in the history of the United States. When it seemed that the fall of the Berlin Wall had buried the geopolitical conflicts, the need of redefining an enemy and its “other” reemerges. This made the artist think a new America was being created, steeped in symbolism and with the need of establishing the new heroes of its epic tales. That is why he bet on a project that was a response to a personal necessity, rather than to a designed strategy to have a profound impact on museums and collectors. As antecedents, there were the facts that in the place where he was born he has only been able to organize one solo exhibition, and that he has been mostly honored in European countries. The artist needed to find himself in his country again, not through an abstract homeland, but by means of the social plurality of the people who have formed the genesis of that nation with their differences and confluences.

Just like Velázquez, Caravaggio, Rubens, Goya, El Greco or Poussin, he goes back to the portrait technique to translate reality. His characters speak for themselves; they go beyond the apparent smiles in some, or beyond the silent look in others. The fireman, the butcher, the Jew, the Muslim, the Klan representatives and the homeless, the FBI official, the children, the clown, the stewardess, the cook of Chinese origin, the nun or the neonazi, next to figures from the art world as renowned as Robert Altman, Yoko Ono, and Arthur Miller, they make us see a country that is firmly resolved to conquer, and that still is the most “conquered one” and diverse in its initial genesis and current configuration. Seeing all the gallery of faces, we feel the validity of some of Jean Baudrillard’s reflections in The Illusion of the End, in which the French philosopher indicated that the historical leap had been replaced by an infinite fabric of ideologies and parties that coexisted as a sort of inherited archeology in the course of the modern project.

Andrés’ portraitsofAmerica stand out for the brilliance of the warm colors, starting from the way he handles the backgrounds to shore up the splendid treatment of the characters’ psychology.

Along his career, Serrano has produced other series I have not mentioned: The Interpretation of Dreams, Objects of Desire, The Church, Istanbul, and Budapest. It is impossible to analyze all in the brevity of this text. Shit, his most recent proposal, goes back to the abstraction with naturalist basis. When we talked about this, Andrés confessed to me that for him it was the most difficult thing to do, until he faced the challenge. Maybe that is what he missed in Body Fluids. In the series, he presents the autonomy of solid waste, which creates other figments provoked by chance together with our optical illusion. Animals, people, we all come together and meet in the imagined constellations of our residues to resort again to the formal classicism he has got us used to.

Andrés Serrano’s participation at the Eleventh Havana Biennale comes along with a photographic book project about images of Cuba for Taschen, the art book publisher. The way the artist is facing this work constitutes a summary of methods used in former pieces, with all the contrasts of a man who was born in New York but has his mother’s Cuban blood in him. Portrait, architecture, landscape, there is no unique way to capture the energy of a context. He has outgrown Havana, and today he draws upon the entire island. I have heard many artists say that it is very difficult to have control over the supersaturation of light in Cuba: that is why this creator resists opacity and leaves illumination in a small cone.

In a recent review by a magazine’s editor about the series America, he said Andrés Serrano had assumed the United States as his adopted country. The artist confronted this comment pointing out that it was an erroneous assertion because he had been born in New York. In this way, he held the critic up to ridicule and brought out into the open a statement biased by racial prejudices. However, that feeling of belonging to the United States does not make him renounce to the energy that comes from the Cuban and Honduran roots that have also helped him to understand his identity.