INTERVIEW WITH VEERLE POUPEYE

Born in belgium and based in jamaica, veerle poupeye is an art historian and curator specialized in the caribbean visual production. She presently works as the executive director of jamaica’s national gallery. She has published such books as caribbean art(1998, thames & hudson) andmodern jamaica art(1998) jointly written withdavid boxer.

First of all, I would like to ask you how you started working with art history and review, and what the origin of your relation with the Jamaican art really is.

First of all, I would like to ask you how you started working with art history and review, and what the origin of your relation with the Jamaican art really is.

I began working as an art historian in Belgium; I had just gotten my master’s when I came to Jamaica. I was mainly specialized in Belgium art, Dutch art from the 15th century to date, with particular emphasis on the modern and the contemporary. So I had an entirely different study area.

Two weeks after landing here, I got a job at Edna Manley School –which was Jamaica’s Art School in that time–, and a couple of weeks later I also began working at Jamaica’s National Gallery, as a volunteer at the beginning, and afterwards in the Education Department.

I came to Jamaica in times when many exciting things were taking place in the world of art. There were some emerging creators such as Milton George, Omari Ra, Khalfani Ra and many others. I started getting involved with their work. I never planned to be specialized in Caribbean or Jamaican art; it just happened, it became my main focus as art historian. In the late 1980s we held a Caribbean exhibition with artists that came from Trinidad, Barbados, Cuba, Haiti… That was back in 1987. I had arrived in here in 1984 and gained several contacts in the area. I started attending conferences and exhibitions in other countries of the region; so, it was not only Jamaica, but the rest of the Caribbean.

During that time, you carried out an exhaustive curatorship work, didn’t you?

My curatorship work comes down to just a few things. I’ve been in charge of Young Talents Exhibitions, as well as other projects that I have developed on my own. I’ve handpicked four artists who worked with me at Edna Manley School, some of my students and colleagues: Marlon James, Stefan Clarke, Leasho Johnson and Megan McKain, because I think that I know them and understand them. Nowadays, I can’t be the curator of an entire exhibition because I have a lot of paperwork to do. The National Gallery is presently facing a serious crisis; the Government is also dealing with it, so most of my attention is focused on that matter.

The Gallery is growing, but it still allows me to do some related work, and I’m also working on some publications. It’s not that my not being academically active; I’m still active, but my main responsibility is to the National Gallery, and it targets the development of programs to assure money income to work. So I hope that, one day, I can aim my efforts at the curatorship.

How would you conceptualize the role played by the National Gallery in the promotion of Fine Arts, and specifically the promotion of young artists?

National Gallery is Jamaica’s National Museum of Art, isn’t it? So it’s in charge of documenting, preserving and promoting Jamaican art and related materials; not only Jamaican art, but that’s the center of attention. As for young artists, institutions like the National Museum of Art don’t get involved in their promotion; it’s usually up to non-profit promotion organization, special institutions and others. But, since there aren’t many cultural institutions in Jamaica, we have to play that role. In that sense, we have access to young artist, and we have the National Biennial, as well as the National Summer Visual Art. They are all exhibitions that feature a serious deal of young artists. Young Talents is a special program that makes it easier for young artists in Jamaica to obtain national promotion. It’s unlikely to find 21 year-old artists in other countries exhibiting at the National Museum, so that’s clearly an additional role played by us. It’s not easy because we have limited resources and there are many young artists and all of them want some attention, but we do our best to support them through exhibitions or acquisitions –when we can afford it–, as well as other programs.

How is digital work being developed? How is the Gallery’s blog doing?

How is digital work being developed? How is the Gallery’s blog doing?

Ah, it’s doing great. We currently have over one hundred visitors a day, which is appropriate for a relatively new blog, in a small country. That’s the enjoyable part of my work, because the paperwork isn’t so. But it’s just another way of getting to know people and allows us to be accessible for the Jamaican Diaspora, because there are people that can’t come to us, so we reach them through a different way. And it’s for free. It entails tons of work, but I believe that it’s also amazing.

Now that you have mentioned it, let me ask you about the relationship between the Jamaican art on the island and the Diaspora’s.

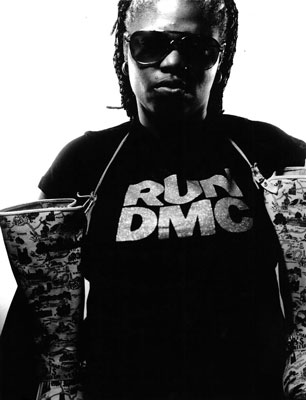

That’s very complicated, because it all depends on how you define Jamaican art and who defines us as Jamaicans. Over the last twenty years, we have worked hard, actively, in order to encourage Jamaican artists overseas to hold exhibitions here. For instance, we have included acclaimed artists such as Renee Cox, Albert Chong, Nari Ward... It’s very hard because they work under circumstances in which they are used to obtaining financial backing from museums, and we can’t afford it, so we have to find other ways, we have to trust in the good will of artists to work with us.

But, know what? If you review what we have done in the last twenty years, we have done a good job. Almost every prestigious Jamaican artist, who lives overseas, has exhibited works here, in one way or another. We need to do it more frequently, and we’d like them to come more often, because we can’t afford bringing them for workshops, conferences and other events, but Jamaican artists living abroad know that we are at their service and if they want to showcase their work at the National Gallery, they can come here.

Allow me to take the conversation to the Caribbean Art book. It was one of the first academic texts, if not the first one, which tackled Caribbean art as a whole. How did you start working in the project?

It was a commission. They wanted a book with an overall view that provided an outlook instead of a profound study on some particular nation. It also makes up the Mundo del arte series by Thames and Hudson, and that series, as you know, targets all kinds of readers; is used at academic level, but is not a textbook, not a truly academic publication as such …

So, when you read the book, you need to be aware of what its target audience is, and it was kind of written for Caribbean readers, but it was actually aimed at international readers, including people who know nothing on the Caribbean. So you need to focus your attention on how you write that kind of book. As you have said, there wasn’t any precedent; there were some exhibition catalogues, particularly Caribbean Visions’ and other. They also included essays written by different specialists; therefore, it was the first time, as far as I know, that one author had to do something like that.

And it was a special challenge because the Caribbean is small, but also huge since it’s highly fragmented. Everything happens in different ways in different places. We can only provide the best overall idea possible, from a specific approach and moment. What I didn’t want to do was creating a brand of Caribbean art. And that has been the problem because, though I made clear in the book that it wasn’t my intention, many people still read it that way: as a label, a sort of specific identity, like a declaration of the Caribbean art being “this way”. It has been hard. There are some people who still ask me how I define Caribbean art. That’s actually frustrating, you know? I never meant to bring about such a response. In fact, I was focused on exploring, on shedding light on the range of possibilities in the region, instead of reducing them to specific definitions. But people read what you write in their own way.

And it was a special challenge because the Caribbean is small, but also huge since it’s highly fragmented. Everything happens in different ways in different places. We can only provide the best overall idea possible, from a specific approach and moment. What I didn’t want to do was creating a brand of Caribbean art. And that has been the problem because, though I made clear in the book that it wasn’t my intention, many people still read it that way: as a label, a sort of specific identity, like a declaration of the Caribbean art being “this way”. It has been hard. There are some people who still ask me how I define Caribbean art. That’s actually frustrating, you know? I never meant to bring about such a response. In fact, I was focused on exploring, on shedding light on the range of possibilities in the region, instead of reducing them to specific definitions. But people read what you write in their own way.

Is it presently possible to articulate some common discourses from a Pan Caribbean artistic and aesthetic policy?

I wouldn’t say that because, again, I’d rather place emphasis on the diversity in the Caribbean; any attempt of articulating a vision will have to deal with it. Obviously, when you look at the Caribbean just like the book did, there are certain matters that persist, elements that appear in the same way; but I see them just like in the mathematics, the value in the graphic. It’s actually a kind of trajectory that tries to reappear –appear– in the Caribbean art, but I’d rather exclude nothing, nothing else. My position is from the Caribbean and for the Caribbean.

What are the main conflicts faced by the Caribbean art?

Insularity is one of the elements. From a certain approach, it allows a unique outlook, a strong one, in favor of the independence; but the lack of promotion is another matter. Besides, you have the feeling that you have to face the rest of the world. One of the problems is the social power of artists; I mean, it’s a problem here, because if you look at the world of art in North America or Europe, there are many artists, but just a few get significant attention or critical recognition; while in Jamaica, for instance, people that start painting today want to exhibit at the National Gallery tomorrow. If they don’t achieve it because of the worth of their work, they will do it through their social contacts, and some artists count on powerful social contacts.

The art market is another validation way, so the review validation doesn’t mean much in Jamaica, because what we try to establish at the National Gallery works in a limited environment, and we have to compete against the local market. It’s like fighting against what people want in terms of what the market wantsand what we believe is to be exhibited at the Gallery. And the market in Jamaica is very conservative, but extremely powerful. Therefore, who are we to tell an artist that sells five paintings in a week that can’t exhibit at the National Gallery? We face the same problem in Bermuda, in Barbados, in Trinidad, and so on; those are the validation systems: social class, social power and market popularity.

What has been the major achievement so far in terms of art development?

What has been the major achievement so far in terms of art development?

I couldn’t say. Fascinating things have happened. During the colonial period, I can talk about a criollización process in the works, which was truly interesting. Belisario, for example, is not a “great artist” but his work stands out cultural and historically. If you review the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s decades, the nationalist movement, interactions with modernism, Wifredo Lam and son on… evidently something very powerful was happening, the Caribbean was being formulated from the economic, the cultural and the politic, getting involved with the idea of modernism in a context. I believe that every Caribbean country can have an outstanding figure. And it can also hold interesting contacts with the rest of the region: for instance, the struggle of surrealists in the Caribbean during the Second World War represented a strong movement;and the Black Power during the 1950s; the independence; the Cuban Revolution, all of them brought about the beginning of a truly complex political moment. It was also a period of time when art and politics were tightly connected: Cuban posters, Puerto Rican posters, the work of artists such as Karl Parboosingh in Jamaica…

And recently, during the 1990s and the first decade of the new century, the contemporary art has taken big steps, so we’re not far enough to fairly review it. But I think that, taking into account what has happened in Cuba, there is a new range of possibilities when it comes to finding Caribbean artistic languages, capable of “talking” in the international arena. Artists like Kcho have had a significant impact, as well as creators such as Ebony Patterson in Jamaica, who are deeply rooted in the here and now of the Caribbean, but also “communicate” with the rest of the world. It’s a powerful testimony; important for the global contemporary culture.

Do you believe possible to formulate a general idea on the Caribbean art now, when the Diaspora and other phenomenon have enlarged the Caribbean cartographies?

My guess is that any general idea, in anytime, will be brief, the synthesis of a particular situation, of a specific context. You might be right. It has become harder because artists from the Caribbean Diaspora are pretty-well represented worldwide. They have surpassed the locals in terms of international profile. And we must also keep in mind that the Jamaican Diaspora and the Caribbean Diaspora are growing older: you have a second generation, a third generation, and creators whose parents might have been born in Jamaica, at least one of them… That’s the reason why the definition of who make up that Diaspora is also changing and is being continuously redefined in terms of the relation with the present Caribbean…

What about the enthusiasts of Jamaican art?

Well, that’s sad in a certain sense because the problem with the people who follow the Jamaican art is that they prefer “Fine Arts”, at least they do right now. Once again, it depends on the kind of art; there is a bigger group of spectators for the contemporary, but it’s mainly made up of foreigners. The local group in this case is very, very limited.

On the other hand, there is an international public for the most established part of Jamaican art, but it’s not big. It’s not like Wifredo Lam or something like that. You don’t have the equivalent in Jamaica, you have it in some Caribbean countries, but acclaimed artists have their own public in the region, in their homeland and within a class of collectors, cultural managers and experts.

We have a lot of scholars interested in what we are presently doing, so we keep our hope that it’s not only about obligation, but they will voluntarily come back to National Gallery’s halls. But I also think that we have begun to see a younger generation of Jamaicans, most of them have studied and come here for pleasure, they come because they want to. [She laughs]

The same situation reappears in the Caribbean, and that has represented one of the main entries for the international promotion of Cuban art.The public attending Havana’s Biennial is made up of the international artistic community; it’s not Cuban, is it? In fact, this has brought about some debate in Cuba: how can you connect this Biennial with the local population. Any attempt of doing has been superficial…

Anyway, everything changes, so I can’t say “this is this” or “this is that”, because within five years we might have a completely different situation. But I believe that it will always be linked to the classes; that’s my experience… That’s how the Caribbean works! [She laughs]

Do you think that some present artistic discourses are aimed at an international artistic sphere, adopting a special language?

Yes I do, because the world trends toward a fixed vision, stereotyped, on what being Caribbean means, what being Jamaican means. And artists, of course, if they choose to follow the trend, are aware of the rules in this game: if you fulfill what’s expected from you, in that context, then you almost gain some promotion … The most interesting takes place when the creators works with that tension or expectations, answering to them, challenging them. But there is also the risk of resignation, which has a lot to do with how the Caribbean is “understood”, because we haven’t reached a stage in which artists “speak” the correct theoretical language …

Artists interested in being put on the map, no matter what, make a show of the hybrid character of their proposal. I’m kind of skeptical in this matter because I believe that hybridization provides a clue on the fate of the Caribbean, but when it comes to finding an authentic voice, you have to look for the integrity in your context. If you only follow the crowd you can obtain lots of promotion, some reviews … When all is said and done, the work still has to be “worthy”, even if it’s not a matter of making it appear in terms of critical and theoretical discourses. And I think that when it comes to curatorial work in the Caribbean, the same parameters are easy to be followed … and that’s why you see the repetition of exhibitions over and over.

Tell something about your present research.

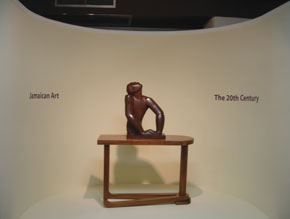

I’m currently finishing my doctoral thesis, which tackles the study of art and society in Jamaica during the 20th century. It’s a huge topic and has compromised some of my time at the National Gallery and, previously, at Edna Manley School. I’m looking forward to finishing it this summer. The chapter to be completed is deals with popular culture. I was recently working with tourism and visual creation because I’m interested in the “touristic art” as cultural phenomenon. I think that it’s easily underestimated, and it’s important because touristic art is the bulk of the artistic production in the Caribbean, whether with like it or not, most of it can be problematic but still you need to learn and accept it. In fact, this project was part of my work at Edna Manley School as research member, so it also makes up my doctoral thesis, but it will also entail other publications and, as the matter of fact, we want to hold and exhibition on this matter at the National Gallery. Besides, I’ve been doing some reviews of Jamaican art, you know, just like my essay on the Intuitive for Small Axe,[i] setting some concepts apart and observing the whole, observing the narratives and concepts that defined the Jamaican art and, afterwards, trying to understand them better, trying to “review” them in a carefully worked way to continue with new reflections. But the main focus of my work is Jamaica: I can’t be constantly traveling alone around the Caribbean. So, until I can step backward and see a wider outlook, this country takes all of my attention.

[i]Small Axe is a Jamaican publication devoted to cultural and artistic review. Further information at: http://www.smallaxe.net/