"A time came in which organizing the information became more important than the subject being dealt with. And that has meant taking a turn that scatters curatorial practices. A symptom of what we could call cognitive capitalism. That means power has a lot to do with information control. I think it is important to cut short an artistic system in which this attitude in curatorship predominates."

CAROLYN CHRISTOV-BAKARGIEV, in El País Digital, 25.05.12

Last June 9th in Kassel, Germany, with the leitmotiv Collapse and Recovery and under the artistic direction of Italian-American curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the doors of the most influential and eagerly awaited exhibition in the art world opened up: dOCUMENTA (13). With 150 participant artists from 55 countries and an exhibition area of 1.5 km2, the Documenta is, no doubt, one of the events of greatest significance and worldwide impact of its kind.

“Art is the criticism of reason”. With this lapidary phrase Issa Samb, a Muslim artist from Dakar, began his performance-installation La balance déséquilibrée (Out of Balance) at the Aue Park, one of the venues of dOCUMENTA (13). On the branches of tree number 174 in this monumental park, the Senegalese installed little African rag dolls, dry pumpkins and cloths of different colors and sizes that flied to the wind suggesting a primitive altar in harmonious union with Mother Nature. Below, on the ground, a table with a black cover showed piles of worn-out and burned books, tied up with coarse ropes trying to preserve the remains of dubious learning. At one side of the table, a cross made of rough wood seemed to prop up the shabby surviving set made up by the table and the books. Scattered on the ground, moreover, lay other crucifixes denoting signs of decadence, fall and death. To the right of the installation, an ultra-flat screen monitor showed a light and lively African comedy.

From time to time, with the sovereign presence of a shaman, Issa Samb went around the installation and recited fragments from his own texts. “By means of this installation –he said– we want to propose a natural therapy to heal man, the inexorable destructor, and in this way, prevent the inevitable self-destruction”. Towards 6:30 in the evening, when the sun started to fade and a cold spring breeze got me out of the magical atmosphere the installation radiated over me, one of Samb’s assistants began to pass around the audience a wooden bowl with a white liquid. Standing up in a ceremonious attitude in front of each of those present, he would offer the bowl so the required person could introduce the index finger into the liquid. Immediately after, he would warmly squeeze in his hand the wet finger of the visitor in question and repeat the same action with the next person.

About 200 meters from there, Mexican artist Pedro Reyes had built a Sanatorium for patients with modern metal disturbances. Anxiety, depression, loneliness, isolation, stress, dissatisfaction, violence, overstimulation, and nomophobia –that inability of today’s man to get rid of the mobile phone–, were some of the disorders on the agenda of Reyes’ “provisional clinic”. A group of assistants analyzed the members from the audience who had registered as clients at the sanatorium. After the diagnosis, totally free, the patient had the right to participate in three therapy sessions that could be or the classical hypnosis, Gestalt, psychodrama, primal therapies, or even therapies that came from popular rites and Fluxus happenings.

About 200 meters from there, Mexican artist Pedro Reyes had built a Sanatorium for patients with modern metal disturbances. Anxiety, depression, loneliness, isolation, stress, dissatisfaction, violence, overstimulation, and nomophobia –that inability of today’s man to get rid of the mobile phone–, were some of the disorders on the agenda of Reyes’ “provisional clinic”. A group of assistants analyzed the members from the audience who had registered as clients at the sanatorium. After the diagnosis, totally free, the patient had the right to participate in three therapy sessions that could be or the classical hypnosis, Gestalt, psychodrama, primal therapies, or even therapies that came from popular rites and Fluxus happenings.

Another participation project that proved this Documenta’s marked interest in states of mind, were the group therapy sessions Anger Workshops by Australian artist Stuart Ringholt. In the middle of one of the exhibition rooms at the Neue Galerie, another Documenta venue, Ringholt had a smaller room built of about 10m2 with just one access door. Workshops involved several sessions. The first one was five minutes long and had house music in the background, participants were invited to express, face-to-face with each other, stress and repressed anger by screaming loudly, gesturing and body movements. The second one, three minutes long and with music by Mozart, was meant to express mutual respect and love with phrases like “forgive me for having mistreated you” or “this is nothing personal against you” or “for you with all my affection and respect”. In the third phase, also three minutes long, participants embraced each other and cuddled. To finish, the group would sit and comment on the experience. From the outside, visitors in this room would not only see the artworks exhibited there but could also listen to the noises and exclamations coming from the closed room located in the center where, at the same time, these different sessions of the workshop were successively taking place.

Feeling excited and thankful for all those personal experiences that in so little time I was given by the artistic proposals in Kassel, I decided to pay a visit to the Fridericianum. Actually, it is around here, by tradition, where people begin to see the Documenta. But there was so-so-so much to see in each and every one of the thirty-two different venues at the Documenta scattered all along Kassel (without including those extended to Kabul, Alexandria and Banff) that, despite the exhibition order in the official program, I thought it best to allow myself to get carried away by intuition and spontaneity.

The Fridericianum is a classical-style palace and the main venue for all Documenta exhibitions since 1955. There, a white rectangle of more than 560m2 and 80 meters long opened up, as infinity, while my eyes popped out of my head in astonishment. For a few seconds I could perceive, not without certain stupefaction, the presence of nothingness. In the white walls and clear floors, emptiness dominated. On the verge of retracing my own steps, I realized that in the right wing of the lobby there was a showcase on the wall with three little sculptures in bronze and iron by the already departed Spanish artist Julio González. On one side of the showcase a library photo, in black and white, showed two visitors from the audience, a man in a suit and a woman properly dressed but barefoot, watching the same sculptures that had been exhibited 53 years ago, exactly at the same spot where they were now.

The Fridericianum is a classical-style palace and the main venue for all Documenta exhibitions since 1955. There, a white rectangle of more than 560m2 and 80 meters long opened up, as infinity, while my eyes popped out of my head in astonishment. For a few seconds I could perceive, not without certain stupefaction, the presence of nothingness. In the white walls and clear floors, emptiness dominated. On the verge of retracing my own steps, I realized that in the right wing of the lobby there was a showcase on the wall with three little sculptures in bronze and iron by the already departed Spanish artist Julio González. On one side of the showcase a library photo, in black and white, showed two visitors from the audience, a man in a suit and a woman properly dressed but barefoot, watching the same sculptures that had been exhibited 53 years ago, exactly at the same spot where they were now.

With this curatorial-exhibition-quotation, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev had not presented herself with a mere historical reference, a Documenta within the Documenta. Her intention was quite different. She had rather set her mind on a reflective return to the original motive of this world exhibition of contemporary art that came into being in the early fifties. In the beginning, the organizers of the Documenta wanted to show the great audience the art censored by National Socialism. Likewise, they were contributing to the reconstruction work and mourning which at that time had an important place in the life of the Second World War survivors. In all three sculptures by Julio González, the human figure stands out as the central theme of the artwork. Which meant that by subtly calling the attention in this empty room to such an exhibition remake, Christov-Bakargiev did not only want to vindicate the foundational origins of the Documenta, but also to visually justify the humanist outreach of a curatorial concept that is distant from the market and the artistic mainstream.

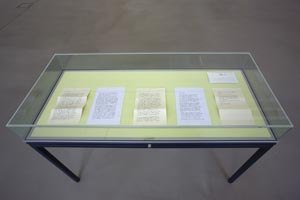

In contrast, in the empty room in the left wing of the lobby, there was also another detail in the form of an artwork-document. ln a little table showcase, Christov-Bakargiev, with artist Kai Althof’s permission, decided to show the letter he had sent her explaining why he declined to participate in the Documenta. This action by the curator, the way I see it, proposes a reading about the controversial relation artist-client which, at the same time, connects us to the most significant of all so far, the Documenta 5 by Harald Szeemann.

It was from this fifth edition on, that the then considered “museum-unworthy” art began to acquire true significance and international visibility. It is the case of Gustav Metzger, whose artistic proposal and epistolary exchange with Szeemann are well documented in the Documenta 5’s catalogue. Invited by the latter to participate at the Kassel exhibition, the artist proposed, from his concept of Auto-Destructive Art, an artwork whose carrying out was so brutal and dangerous that at the last moment, even Szeemann himself, who had insisted so much on Metzger’s attendance, was forced to decline his participation.

It was from this fifth edition on, that the then considered “museum-unworthy” art began to acquire true significance and international visibility. It is the case of Gustav Metzger, whose artistic proposal and epistolary exchange with Szeemann are well documented in the Documenta 5’s catalogue. Invited by the latter to participate at the Kassel exhibition, the artist proposed, from his concept of Auto-Destructive Art, an artwork whose carrying out was so brutal and dangerous that at the last moment, even Szeemann himself, who had insisted so much on Metzger’s attendance, was forced to decline his participation.

Be that as it may, the finishing touch on these two empty rooms in the lobby of the Fridericianum was put by the artwork I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorise(The Invisible Pull) by the English artist Ryan Gander. While disconsolate spectators like me were looking for things to see, every now and then, and in spite of all windows being closed, an unexpected breeze blew in the rooms enveloping us all from head to foot. It was the “invisible pull” of Gander’s artwork. An impossible work to see or touch, but which showed its silent power.

For me, in this experience in the empty lobby, the exhibition essence of all the dOCUMENTA (13) was summed up: an art whose strength and efficiency do not lie in its physical volume, but in the evocative power and inner vision of its spirit. Instead of magic and pyrotechnics, a risk was taken in giving the art category to experiments like quantum physicist Anton Zeilinger’s “individual photons teleportation”. But also, sides were taken regarding the ecological and environmental problems by promoting the Public Smog proposal by conceptual activist Amy Balkin, who asks for the Earth’s atmosphere to be included, with all corresponding rights, on the UNESCO World Heritage List. “dOCUMENTA (13) –Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev wrote in the catalogue– is driven by a holistic and non-logocentric vision that is skeptical of the persisting belief in economic growth”.

That is why, whoever went to Kassel looking for strong emotions, to see fireworks in a fabricated show by the art industry, failed in the attempt. That kind of spectator symbolically died for this Documenta. There, conservative practices were challenged and bets were made on a conception of art as a whole, in its unity, expanded and without boundaries. A simple run of our eyes over the participants’ list, most of them unknown but with works that place men and their current problems at the center of all worries, gives us the extent of the significance granted to groups and not to individualities.

In short, this Documenta artistically aimed to what should be bet on in all other areas that also make the development of human existence possible. And if art has not lost that ability, its very essence, of poetically getting ahead of events, we should assume once and for all the responsibility of having already entered into another era. An era where the most arduous will not be, as my friend Angel Escobar thought, “to escape from knowledge”, but rather to endow all accumulated wisdom with a true conscience.

Munich, July 13th, 2012