Dolores Caceres (Cordoba, Argentina) is a referent when speaking about public art in the subcontinent. For more than ten years, she has made interventions, actions and works in process qualified for the use of texts and words to recreate the collective memory, symptoms of an epoch, religious faiths, local history and conflicts of her region, from a self-referential perspective. The need to provide the ego and collectivity with a voice finds a particular resonance in public circles where her warning signs can achieve the highest levels of questioning and visibility. In general, her projects are the result of researches on an issue or phenomenon, historical circumstances and the context of the site for the intervention.

Caceres’ work could be taken as an example of the curious alliance between the reflective management of topics through the denotation quality of words and the seduction of advertisement and popular resources, either by means of neon lights, illuminated boxes, logos or gigantic fonts on texts. Certain underlying magnetism has led her not only to use the first person singular and the connotations of her name in the articulation of projects, but also her own physical image. The latter can be appreciated in one of the versions of “Dolores de Argentina”(Argentina’s Sorrows) and the project “YO NO: Espacio Privado” (NOT ME: Private Space). In both works, her body becomes a territory of meaning where the texts written on it refer to experiences marks.

Different from other artists of the continent who have gone through other imageries and representations before choosing the written language,1 in Caceres’ creative exercise the text appear early. The installations “Plegaria para un corazón artificial” (Prayer to an artificial heart) and “Mea culpa” displayed at “El día electrónico” (The Electronic Day) of the Caraffa Museum in 1991 and the Institute of Iberian American Culture (Spanish acronyms, ICI) of Buenos Aires in 1994, respectively were based on the animation of texts like a visual poetry in motion on electronic displays. And although these pieces referred to technological formats and spaces of the art institution, and certain concerns (that would later take her to the public’s reaction) were not in her list priorities, they left an evidence of how long representations based on linguistic constructions had been in her mind to become later a cornerstone of her public work.

Different from other artists of the continent who have gone through other imageries and representations before choosing the written language,1 in Caceres’ creative exercise the text appear early. The installations “Plegaria para un corazón artificial” (Prayer to an artificial heart) and “Mea culpa” displayed at “El día electrónico” (The Electronic Day) of the Caraffa Museum in 1991 and the Institute of Iberian American Culture (Spanish acronyms, ICI) of Buenos Aires in 1994, respectively were based on the animation of texts like a visual poetry in motion on electronic displays. And although these pieces referred to technological formats and spaces of the art institution, and certain concerns (that would later take her to the public’s reaction) were not in her list priorities, they left an evidence of how long representations based on linguistic constructions had been in her mind to become later a cornerstone of her public work.

Her first experience on the urban space is traced back to 1998 in the presentation of her work “YES NO (Maquillaje de museos)”, at the Center of Contemporary Art in Cordoba. On the following year, she was invited to make the same intervention in Buenos Aires, where I had the opportunity to see her display. Something that called my attention was the paradox of texts and places chosen for the intervention with the purpose of enticing people who were not interested in art. The short neon light phrases built with words starting by s of SÍ (YES) (simulacro, silencio, sin sentido, sintesis) and n of NO (nostalgia, nunca, no ser, no quiero) just to mention a few, shined on the façade of the Museum of Modern Art and on an unusual site: the Line C subways where the train’s route ends. As she would later confess it was the best solution she found to achieve the wanted sensation of movement, although in this case it was the trains that moved not the signs. As travelers passed by they were surprised to see the neon light signs on the subways, whose messages of laconic contradiction were enhanced by the quick glance; Buenos Aires was back then at the threshold of the economic crisis of 2010 and uncertainty

was the omen of what came later. The antithesis of the signs would make the chaos associated to a situation of deep emptiness leading to the irreversible dead point YES and NO, whatever.

Those years back then I would define urban intervention as a “means of expression that forms part of the meaning of my work”2 –“at odds with traditional means”–3 that makes it possible to step away from the notion of art as a cultural good and “create a semi-autonomy of the artistic field and convey its logics to public criticism”.4 More recently, and without denying those concepts, Dolores would assess her work as a combination of interests related to the nature of producing art, the role of “doing art” and the meaning of culture in society.

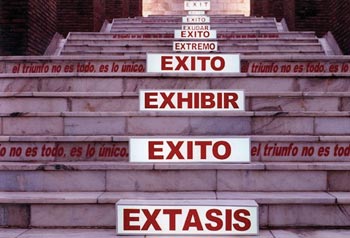

In the First International Biennial of Buenos Aires held in 2000, she made another intervention called “Exit” that is part of the Maquillaje de museos series. Inspired by the staircase to the Law Faculty of the University of Buenos Aires –located close to the Museum of Fine Arts– she worked an allegory in reference to the upward sense of the architectural structure: climb in search of success and solutions. Equally apart from each other, she placed illuminated boxes with one word starting by “e” written on each of them (Éxito,Éxtasis, Exhibir, Extremo, Exaltar, Explotar, Existo); Exit was the last word of the list. With the goal of provoking different reactions, every certain number of steps the phrase: “El triunfo no es todo, es lo único” (Triumph is not everything, it’s the only thing) was repeated.

In late 2001 the economic crisis broke in Argentina. In the 1990s the government of Menem established the (artificial) parity between the Argentinean peso and dollars as a symbol of the economic prosperity of his neoliberal policy that led to the closing of several long-standing traditional industries to give way to multinational companies that brought about flight of capital and increase of foreign debt. Due to the IMF pressure, banks ceased operating and frozen their funds faced with the due date of their colossal foreign debt, given rise to the so-called “corralitos” and readjustment of the currency value. The concentration of picketers, protesters banging saucepans and demonstrations, some of them seeking to recover their factories, although arouse by economic reasons, they would stir up memories of the bloody years of military dictatorship. Halfway way through 2001 the threat of an economic and social crisis was imminent and in September Caceres premiered Dolores de Argentina (discourse of a violence) in the Third MERCOSUR Biennial. The main staircase of the Santander Bank of Porto Alegre, turned into a cultural center and venue of the event, served as support for her intervention. For the first time, she sees herself explicitly linked to the national situation in the textual construction of the title and the staging of the work, clearly stating her awareness of the current circumstances of the country. On the first step she placed her year of bird, 1960, and later she states on each of the following steps all the “painful” events of the history of Argentina up to then.

A new version of Dolores de Argentina was later presented at the Ninth Havana Biennial, 2006. It consisted on six chairs –metaphors for torture– upholstered with a plane of Buenos Aires and facing six iron boards on which all the painful events written on the staircase of the Santander Bank of Porto Alegre were also written down. The installation was complemented by a public action. Knowing that the Biennial would include a Costume Workshop, the artist made a long black dress with the phrase Dolores de Argentina (Argentina’s Sorrows) stamped in white and she walked down the centrally located streets of Old Havana wearing the dress in a public demonstration of her denouncement and as an extension and promotion of her work. The street performance, a mixture of the exhibitionism entailed by the presentation of a garment and the mourning for the events she was referring to, enabled her to get in touch with the people in Havana and foreign visitors to the Biennial among who she distributed t-shirts with the same sign.

A new version of Dolores de Argentina was later presented at the Ninth Havana Biennial, 2006. It consisted on six chairs –metaphors for torture– upholstered with a plane of Buenos Aires and facing six iron boards on which all the painful events written on the staircase of the Santander Bank of Porto Alegre were also written down. The installation was complemented by a public action. Knowing that the Biennial would include a Costume Workshop, the artist made a long black dress with the phrase Dolores de Argentina (Argentina’s Sorrows) stamped in white and she walked down the centrally located streets of Old Havana wearing the dress in a public demonstration of her denouncement and as an extension and promotion of her work. The street performance, a mixture of the exhibitionism entailed by the presentation of a garment and the mourning for the events she was referring to, enabled her to get in touch with the people in Havana and foreign visitors to the Biennial among who she distributed t-shirts with the same sign.

The years 2007 and 2008 were also fruitful in Caceres’ career. Upon her return from the End of the World Biennial hosted by Ushuaia in 2007, a colleague told me Caceres’ proposal El artista señala (Artists say) anchored by the Beagle Canal, the southernmost area of the continent, was very well received by the public. According to my colleague, Caceres blend resources and codes to invoke the site’s latent senses: an ephemeral (as it was the existence of Yamanas, native peoples who disappeared many centuries ago) action of fire (in reference to the name of the region “Tierra del Fuego”) created a poetical atmosphere of recollection, emanated precisely from the combustion of the large phrase.

A little later, Caceres made another intervention called site specific of the Maquillaje de museos series as part of the Resplandores exhibition. The cemetery next to the Recoleta Cultural center, former Convent of the Recoletos –the name of the first person buried there after it became a public necropolis was Dolores–, served as inspiration for a work of plural meaning. Being a tribute to all the heroes, artists, politicians and intellectuals lying in the graveyard (Eva Peron, Juan Facundo Quiroga, Carlos Gardel, among others), the artist questions the endurance of the values represented by them, perpetuated in the mausoleums erected to their memory under the title “Accept to dissent (before being buried).” The neon light phrase placed at the top of the façade of the Recoleta center generated a subtle dialogue between the cemetery and the square, the past and the present, the personalities and historical contexts.

In 2008 Caceres carried out the NO series of public works whose only gallery version was selected in the Roggio Visual Arts Prize. For the series designed for the open air she turned to a billboard, which is a means of advertisement of greater scope previously intervened with a similar purpose by Panamanian Gustavo Araujo, and others. The occupation of the billboards on downtown Cordoba for several months with gigantic texts (NO y BASTA, YA NO, etc.) of this series, plus several sextuplet illuminated posters raised different questions depending of the experiences of each viewer.

The creation of mechanisms for representation that take shape in written language and can be used in the denomination of projects inserted on the public space in an autonomous way or the intervention of buildings using formats, structures and materials that facilitate its visibility and mixture with specific actions have been a constant in Caceres’ career. Her public work is characterized by texts and actions, though the latter was not introduced until a few years ago. To carry out her actions, she stars by a multidisciplinary approach through which she introduces logical reasoning and behaviors of human activity in relation to the phenomenon or situation to be addressed. When it comes to working on the actions’ simulation and drama based on referents taken from reality, her projects are highly receptive and raise questions about its possible messages. She put into practice a similar strategy in her site specifics works that have been very well received on international biennials. However, it is the city where Caceres’ public projects reach their broadest senses and become a resonance box of the targeted different process. Such was the case of a project named QUÉ SOY (What Am I) placed on the exterior areas of the Caraffa Museum. The city of Cordoba, home of the museum, became a laboratory of the dynamic generated by intervention process, whose highlight was the activation of the viewers’ capacity for analysis.

QUÉ SOYturned the spotlight on an issue of national and international interest: the exploitation of new energy sources –which means fast money to others– that is leading to enormous transformations not only at the economic and environmental, but also in demography and the countries’ identity. Because of its regional extension and the fact that soy –whose oil is used for biodiesel production– is a plant originally from China, the project is an eloquent metaphor of the planet’s connectivity and the place of market in today’s world.

Caceres has shown a great talent in condensing meanings into a few words. In QUÉ SOY she blended the global and national dimension of a conflict –the impact of soy on the social, political and economic life of Argentina–5 within a question comprising the first person singular, society and the name in English of the plant. The planting and harvesting of soy in the Museum’s gardens (that became “exotic” for that reason) where the public could see it between December 2008 and April 2009, the intervention of billboards with the logo and screening in an exhibition hall of the video “Sobrentendidos”6 (where she interviews taxi drivers), added to headlines about debates on the increase of deductions from soy exports7 on the glass walls of the Museum gave rise to demonstrations8 and polemic that surpassed initial expectations. The meaning the growing of soy (to the government and the rural sector, for local interests and transnational capital), the defense of old crops that shaped the country’s identity and culture, protests over the cutting of forests and ecologic imbalance associated to monoculture of transgenic soy, and even the role of artists and art institutions (what is art, what is being an artists, what is the museum) and the boundaries between art and pretend art were at the heart of debates. By linking art and life, museum and street, Caceres raised questions about respective limits and also about the public and social role of art.

The participation of artists in the planting of soy, the reaction of the media and different sectors in the community, added to a highly aggressive digital tool like blogs supported by a portal with images of the “work in progress” that included parodies inspired by associations with works within the history of art (like Las espigadoras, by Jean-François Millet regarding the planting scene, and Payment of Argentina’s Foreign Debt to Andy Warhol by Marta Minujin, this time with soy instead of corn) generated a weave of relations between art and other fields of human activity, social, media and virtual spaces that had barely seen before.

The participation of artists in the planting of soy, the reaction of the media and different sectors in the community, added to a highly aggressive digital tool like blogs supported by a portal with images of the “work in progress” that included parodies inspired by associations with works within the history of art (like Las espigadoras, by Jean-François Millet regarding the planting scene, and Payment of Argentina’s Foreign Debt to Andy Warhol by Marta Minujin, this time with soy instead of corn) generated a weave of relations between art and other fields of human activity, social, media and virtual spaces that had barely seen before.

The impact of Caceres’ texts and actions concerning topics of local importance, of general interest and ongoing events, and the extent to which they encourage the participation of heterodox publics in works that lead up to critical reflection have been cornerstones in her project’s social mediation and likely the reason behind their success even beyond the national geography. Hence she is tempted by a greater challenge: planting in China soy seeds harvested in South America and have the Chinese public involved in what is happening in her region. With this regards, her project represents the current trends of public art towards the relational practice of multicultural subjects, and have the artistic fact intervene in the dynamics of cities like a living being where the political, social, cultural and economic sectors get contaminated with each other and as a consequence art hardly preserves the autonomy it enjoys on its own spaces. That’s the key, having developed it on the edges of the artistic field and raising questions about the friction among all those involved and their roles. For now, Caceres has the intention to take it to the Museum of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, to the Blanes Museum of Montevideo, Uruguay, after it is closed at the Museum Niemeyer Museum of Curitiba, Brazil, which has already extended an invitation.

In August, 2009, Caceres was invited to the Curitiba Biennial. There she presented “Amen” , a work that examines “the presence and fusion of religions in Brazil, the country with the largest number of Catholics of the world coexisting with Syncretism, Umbanda and the new universal churches that have been quickly winning faithful followers,” as Caceres says. Once again she finds in words the ideological and aesthetic artifice that will enable her to reconcile the different religious beliefs and the encouragement to achieve greater participation of the people. The graphic structure of the world amen, in gigantic format and located in a public place became a sanctuary for countless candles lit by the people at the invitation of Caceres as an offering or plea according to everyone’s needs and beliefs.

One of her most recent proposals came to light between late September and early October 2010 in Villa Carlos Paz alongside the mountain ranges of Cordoba, as part of an exhibition of public art named Afuera (Outside)9 in this city. Proyecto CUCÚ. Trilogía (CUCKOO Project. Trilogy) was born out of the intersection of two situations associated to tourism, which is the main economic activity of the Villa. On one hand, there is threatened endemic birds as a result of the indiscriminate shooting encouraged by a tourist entertainment and on the other hand, the scenes around the big Cuckoo Clock which also attracts tourists and locals who want to have their pictures taken next to this exotic architecture of rural style,10 while watching the ritual of the wooden bird announcing the time. The orchestration of artistic operations put into practice seek to bring the attention on the extermination of birds and the finite nature of humans as oppose to the perpetuity of the machine demonstrated on the unstoppable mechanism of the clock that sets the passing of time, the end of all living beings.

A few days before the inauguration of Afuera, she made the public performance

Yo Pájaro in the urban perimeter where the Cuckoo Clock is located. Before starting, the artist handed out to the people in the public a piece of paper with the love story between the golden pigeon and the mechanic bird of the cuckoo clock written by her; the tale, in which the humanization of the animal world and objects or machines brought to life –like in myths, fables and Disney-like and futurist productions–, is contextualized with denunciation purposes. With the collaboration of the Explosives Brigades of the Province of Cordoba and dressed in hunting clothing, she shot three times the bird on the clock. With the bang of the last detonation, hundreds of carrier pigeons were released and flew away. The pigeons carried in their legs a message reading “Zenaida no llores” (Zenaida don’t cry) (name of the video that tells the love story between Cuckoo and Zenaida, a local kind of pigeon. Same as the planting and harvesting action of QUÉ SOY, the staging of the shooting rapidly brings the viewers into the conflict: the threat of extinction of endemic birds. The sound of the trigger unveils the reality behind the tourist postcard reproduced by the innocent click of the shutter of picture cameras. This way, the performance strengthened and redefined the preexisting uses of the Clock by dialectically linking it to another situation of the context. In this first part of the trilogy, Caceres brings on the senses –usually forged in her creative work by mixing texts and action– from the title of the performance and an almost forgotten resource: written stories. Yo pájaro (Me bird) is a call to take the place of the bird and live its tragedy, while she paradoxically assumes both the role of the pray (“Me”) and the hunter (in the performance). The story serves as a bridge between the three parts of the project (specially between the performance and the installation video) and resolves the gap between irreconcilable worlds with the respective characterizations: through the hypothetical romance between the golden pigeon (abundant in the area) and the mechanical bird of the Clock, between a living being and an artificial creature; she breaks the barriers between reality and imagination, between the natural universe (endemic fauna) and industrial artifacts (of foreign origin), and foresees the relationship between beings of different nature in the perhaps not-so-far future anticipated by science fiction movies. At the same time, she unmasks the falseness of simulacrums built by art and shows how conflicts can be solved by imagination.

A second intervention from the Maquillaje de museos series is staged in them main venue of Afuera, the abandoned building El Panal which has become home of hundreds of pigeons that are killed like rats. The walls on the front of the building are intervened with a neon light sign that reads: golden dove, Zenaida auriculata (her name in Latin). The four words are located separately at the center of respective rifle sights made of the same material. Inside the building, a video installation closes the trilogy. The tape shows a ballerina covered with feathers composing the abstract and stripped steps of a pigeon facing the imminence of danger. As she dances, the fragmented melody of “Cucurrucucú Paloma” in a free version played by a double-bass accompanies her moves that describe how her white feathers get intertwined in the rough surface of an old wall as metaphor of the closure of the city from where she is flying away and meets the cuckoo bird, according to the fiction story created by Caceres. The video Zenaida don’t Cry was screened against a neon sight aiming all the time at the image of the woman representing the pigeon, marked to die.

During the development of the project Caceres said: “I looking for the way to have people see what is still hidden, what is happening and we don’t get to see”… and she adds that in her works she proposes “a crossing place, an interstice”.11 Caceres unveils the reality through other stories, those of her creation, where written words reach the category of images whether they are united or not to action. They are tasks and tactics of her public art12 that, in this case, show the untouchable links between physical spaces, events, and subjects, to talk to us about ecologic predation and the future of the planet.

1Since the late nineties, Chilean Gonzalo Diaz has been developing a powerful in situ installation on neon writing following a first period dedicated to painting. Another case would that of Leon Ferrari and Luis Camnitzer, who turn to texts dictated by the political and repressive situation of the military dictatorship years. Leon Ferrari, to express his rage through the compulsive and powerful use of this resource, and Luis Camnitzer with a view to support the meaning of images of torture and reclusion in phrases that excelled for their sharpness. More recently Camnitzer retook writing, as seen in some of the pieces displayed in an individual exhibition at the 10th Havana Biennial: “Aula”(Classroom) (2005), where by writing a text in two blackboards, she shows the asymmetries of power and in “Ultimas Palabras” (Last Words) (2006-2008), letters written by the condemned of Spanish origin in Texas, United States.

2Comments by the artist for this work via email.

3As Margarita Paksa, a well-known artist of the new media wrote in her article “Makeup is camouflage,” about Caceres’ first public intervention in Buenos Aires. Maquillaje de museos Catalogue; Museum of Modern Art of Buenos Aires (MAMBA), Jun. 1999.

4Ibídem.

5Other Argentinean artists have presented similar projects in favor of traditional crops opposing the soy. In the La obsolescencia del monumento curated by Patricia Hakim, artist Hugo Vidal carries out Diario de la Región, an intervention consisting of huge cotton bales of both poor and excellent quality. With the intervention Vidal gives continuity to his joint work with Cristina Piffer in 2002 in which they installed cotton blocks at the Resistencia square pointing to the contest of sculptures built on one side of the square and, on the other side, to the cotton industry and production crisis as it had been displaced by the growing of soy. See “La obsolescencia del monument,” Mar. 2010, National Collection of Fine Arts, http://www.fnartes.gov.ar

6The “Sobrentendidos” video won Caceres a Mention of Honor of the Andreani Foundation Prize 2009.

7As to the rift between the agricultural sector, once again enriched by food requirements worldwide, and the attempt to enact Act 125 with a view to increase taxes on soy exports that came to an end with the nay vote by the nation’s vice president in 2008, see “Argentina and its disarrays: the passion for restoration” by Alicia ENTEL in “Disposable Knowledge and Indispensable Knowledge”, Competence Center for Latin America, Bogota, 2009.

8Among the forms of expression that paraded before the work on the avenues that cross Plaza España, where the Caraffa Museum is nestled, some highlighted topics were ecology, rejection to transgenic soy and salvage dismantles, and the one staged on March 8 promoted by two feminist groups that tied up the QUE SOY (WHAT AM I?) project to the issue of sexual discrimination.

9Curated by Rodrigo Alonso and Gerardo Mosquera, Afuera shows the sustained progress of public Works. It brought together close to 40 artists from Argentina and other Latin American countries and Europe (the latter in lesser number).

10The Cuckoo Clock was made by two German engineers who donated it to the Villa in 1958 when the plane factory where they worked was shut down after the coup of Juan Domingo Peron. That’s why it features central European traditional patterns.

11“Tres tiros y un pájaro protector”, in the Vos supplement, Diario La Voz del Interior, Cordoba, Argentina, Sept. 22, 2010, http://vos.lavoz.com.ar/content/tres-tiros-y-un-pajaro-protector

12 When I was about to finish this work I received the news of the premiere of Caceres’ latest public project, Enamoradas del muro (In love with the wall), a site-specific work to be in progress until 2013. According to the offprint distributed via email: “the work offers an abstraction of the vegetal idea inspired by the poetry of Uruguayans Idea Vilariño, Armonia Somers and Marosa di Giorgio.” It consists of an intervention in the tower of a new building in Maldonado, Uruguay, that was designed by young Uruguayan architect Diego Montero. Attached to the surface of the building, neon arabesques create an illusion of a plant whose branches grow adhered to the walls like a vegetal embrace. They are sprouts that turned off and so cut short or, on the contrary, are turned on and so bloom according to the plant’s splendor on each season; that’s why it takes time to develop the work of art. The gleaming vitality of the summer (the season in the South Hemisphere in which the intervention was inaugurated), is followed by the falling of the leaves in the Fall (fewer lights), then comes a rest in the Winter (the lights are turned off) and it starts to grow again in the Spring with the blooming of new neon sprouts. The cycle is repeated throughout three years, which means that the work of art will gradually grow to finally cover great part of the building. Inside, sprouts have been hung to the height of the sight so that fragments of verses by the aforementioned women poets can be read on each neon tube. Likewise, it is worth mentioning Enamoradas del muro as a new type of visual poetry for the way in which the artist transforms the coldness and industrial hieratic nature of neon lights into a vegetal and poetic form, into a creeper containing and signifying the lyricism of the verses. Poetry and light together create a symbolic dimension of her site-specific proposal, allegorize and combine moods with the plants’ life cycles. Thus, an inner world of solitude and anguish with certain flashes of happiness (scattered color neon lights), as described in the verses, are reproduced in the sprouts outside. Like Dolores said: “the creeper… is a metaphor of what there is outside and what there is left inside, it resolves the tension between the superficial and the profound.” Enamoradas del muro is an example of her creative versatility when working texts in public works of art, where she highlights the conciliation of the matching game offered by the context (on its multiple readings) with the site to be intervened.