We’re living difficult times. That’s patently obvious; but the complexity we are talking about has to do with an order of global domination that has stealthily banished any positions of resistance, selling us the idea of dais as alternative, otherness, difference. Our post-modernism is the ideal scenario for recycling and readapting certain modern narratives, now under the protection of the free global market. So, it’s not about taking up false standards, but of hiding behind frail shields or seeking protection under nostalgic attitudes. It is necessary to refocus, to identify the object of criticism and readjust the discourses. Many may question the validity of an visual art event like the Havana Biennial may have in the 21st century; or some may wonder how an event like this one, under the current circumstances, is capable of rising up against forms of hegemonic domination without becoming an accomplice or playing their game, that is, without the interference of mechanisms of the critics, and adding them to the logic of the domination. We believe that any event as big as this one should be able to go around those roads: the question is how.

One of the most important lines of action in the organization of the 11th Havana Biennial (founded in 1984) was the commitment to foster reflection on certain substantial matters of the social imaginary, and to open large spaces to critical self-awareness. The Biennial, as a discursive platform, has historically developed a fertile questioning line of the grounds on which the artistic reality was raising; it became a true alternative space and not a mere mediocre disciple or reflection of other international events. Of course, the background has changed a lot after the first biennials took place, but the need to uphold a solid structure to promote thinking and action continue to be one of its maxims.

One of the most important lines of action in the organization of the 11th Havana Biennial (founded in 1984) was the commitment to foster reflection on certain substantial matters of the social imaginary, and to open large spaces to critical self-awareness. The Biennial, as a discursive platform, has historically developed a fertile questioning line of the grounds on which the artistic reality was raising; it became a true alternative space and not a mere mediocre disciple or reflection of other international events. Of course, the background has changed a lot after the first biennials took place, but the need to uphold a solid structure to promote thinking and action continue to be one of its maxims.

Organizing the Eleventh Havana Biennial in 2012 has been a challenge to the National Council of Plastic Arts, in the first place, and to the Wifredo Lam Center of Contemporary Art, in the second, the latter being in charge of the planning, conception, curatorship, museography and promotion. Actually, every edition has been a challenge that has been happily overcome by their organizers against all odds. This year, the event shows once again the flexibility it was conceived and structured with. There are significant changes, not so much oriented to the theoretical grounds or its objectives, but rather to redesigning its venues and exhibition spaces, which ever since the fourth edition have been consistently expanded to a large part of the city of Havana.

It was for the fourth biennial (1991) that then director Llilian Llanes suggested that the Morro-Cabaña Fortresses Complex, in the east of the city, was the ideal spot to deploy a series of individual and collective exhibitions that formed part of the exhibiting essay, and which could not be assumed by the National Museum of Fine Arts –the event’s exclusive venue back then- because of its dimensions. The Morro-Cabaña Complex, with its countless vaults of diverse dimensions and its open-air spaces, was turned into an indispensible icon of Havana’s cartography during the Biennial. The extraordinary physical and architectural peculiarities of the place, added to its historical meaning, made it possible, until the tenth edition, to materialize a coherent curatorial arrangement, and a museography that efficiently developed the works of the selected artists in line with what was considered as the main exhibition. However, this time, and in adjusting to the nature of the majority of the projects submitted, the Biennial is now scattered across a large part of the city. In turn, Morro-Cabaña gives up the preeminence it had enjoyed until the present to other spaces of the urban framework. And the officially called “side exhibitions” –ever since they were first introduced in 1986 when the Wifredo Lam Center’s curatorial group conceived them as a theme and visual support of the main exhibition displayed in different institutions and galleries of the city–, are now clustered in the military-historical complex.

It was for the fourth biennial (1991) that then director Llilian Llanes suggested that the Morro-Cabaña Fortresses Complex, in the east of the city, was the ideal spot to deploy a series of individual and collective exhibitions that formed part of the exhibiting essay, and which could not be assumed by the National Museum of Fine Arts –the event’s exclusive venue back then- because of its dimensions. The Morro-Cabaña Complex, with its countless vaults of diverse dimensions and its open-air spaces, was turned into an indispensible icon of Havana’s cartography during the Biennial. The extraordinary physical and architectural peculiarities of the place, added to its historical meaning, made it possible, until the tenth edition, to materialize a coherent curatorial arrangement, and a museography that efficiently developed the works of the selected artists in line with what was considered as the main exhibition. However, this time, and in adjusting to the nature of the majority of the projects submitted, the Biennial is now scattered across a large part of the city. In turn, Morro-Cabaña gives up the preeminence it had enjoyed until the present to other spaces of the urban framework. And the officially called “side exhibitions” –ever since they were first introduced in 1986 when the Wifredo Lam Center’s curatorial group conceived them as a theme and visual support of the main exhibition displayed in different institutions and galleries of the city–, are now clustered in the military-historical complex.

The number of artists and works proposed to form part of the new artistic network, as well as the thread that would united them as a coherent whole, are two of the points taken into account to come up with a new organization of the side exhibitions, seeing them as a support of the main ideas of the essay or central exhibition.

The side exhibitions–which have received many praises inside and outside the country–, continue to play a key complementary role in the Havana Biennial’s framework; they stand as the largest territory dedicated to Cuban art, with the purpose, on one hand, of “providing the necessary qualitative balance to the project”[i] and, on the other, “to show the widest possible panorama of Cuban art including all the forms of visual art, different generations, expressions and influencing trends, so that the public can appreciate the peculiarities of the local artistic scenario.”[ii] Starting in the second Biennial (1986), a group of exhibitions were conceived to run parallel to the main exhibition, which played a very specific role with the event’s general strategy. Shortly after, the idea was quit, and side exhibitions focused in providing an inventory and a record of the development of the Cuban visual arts as a way to make our contemporary art as public as possible, since some direct advantage would have to be taken from the fact that the venue were Havana.

Many have pointed out the notoriety reached by those exhibitions, especially because they were staged by local creators, making it easier for them to connect and identify with Cuban viewers. Nevertheless, we don’t think that they shadowed in any way the main exhibition: on the contrary, they strengthened it from different angles. The organization of the Eleventh Biennial’s side exhibitions –made up, as in previous occasions, by personal and collective displays– fell completely on the National Council of Plastic Arts and the Visual Arts Development Center.

Among the most relevant individual projects is that of Jose Manuel Fors for La Cabaña Fortress (installation and photography); there is also Piedra angular (Cornerstone)by Humberto Diaz, a site-specificproject where the communion between the viewer and the place where the piece was set allow completing its character. Mayimbe proposes an intervention that originated from the interaction with specific family environments, under the name Entrega especial: el método, no el recurso (Special delivery: the method, not the resource) in which the notion of private and public are in constant confrontation. Condenado (Condemned) by Lorena Gutierrez, plays with the image of a cage as a group reference associated with states of imprisonment and freedom. Meanwhile, Joel Jover sums up his most recent production in Strawberry Fields Forever; based on generational references he goes deeper into the relationship between the individual and society.

Among the most relevant individual projects is that of Jose Manuel Fors for La Cabaña Fortress (installation and photography); there is also Piedra angular (Cornerstone)by Humberto Diaz, a site-specificproject where the communion between the viewer and the place where the piece was set allow completing its character. Mayimbe proposes an intervention that originated from the interaction with specific family environments, under the name Entrega especial: el método, no el recurso (Special delivery: the method, not the resource) in which the notion of private and public are in constant confrontation. Condenado (Condemned) by Lorena Gutierrez, plays with the image of a cage as a group reference associated with states of imprisonment and freedom. Meanwhile, Joel Jover sums up his most recent production in Strawberry Fields Forever; based on generational references he goes deeper into the relationship between the individual and society.

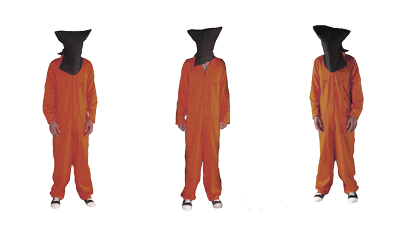

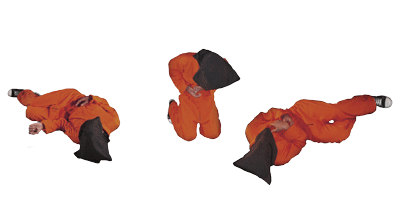

David Velazquez Torres, in Migraciones de sueños (Migrations of dreams), uses sculptures and installations built for an specific space: giraffes, birds and hybrids from a world of chimeras as metaphors of everyday existential conflicts La voluntad de los huéspedes (The guests’ will) by Aluan Argüelles, addresses the link between power and the subject, as he proposes a sequence of an execution process, involving the viewers as accomplices of the reaction of three characters submitted to the action. This interactive piece seeks to provoke viewers and activate their ethical values.

Among praiseworthy collective projects are FLYERS, located in one of the vaulted pavilions of the Castillo del Morro Fortress. The work emerged from a series of questions about creation and the legitimacy of imagination as a quality of the mind. Curated by Andres D. Abreu, the exhibition includes video screenings and paintings by Flavio Garciandia, Raul Cordero, Alejandro Campins, Michel El Pollo Perez, Alberto Lago, El Yaque, Adonis Flores, Humberto Diaz, Luis Garciga, Javier Castro, Marianela Orozco, Carlos Martiel, among others. Many of them see imagination as the legitimate battle ground for individual liberation.

Although most of the exhibition will be staged at the Morro-Cabaña Complex, other spaces in the city are also being explored: galleries, specialized centers, workshops, museums and artists’ studios, where art can be enjoyed in a wide range of sizes, formats and expressions. There is, for instance, Momentum by Yoan and Ivan Capote, set up in their respective studios in El Vedado neighborhood; Proyecto colectivo de escultura exterior (Collective Project of Outdoor Sculpture) will take place in different sites of the city; La verdadera Historia Universal (The true Universal History) by group Cascarilla will be on display at the Amigos del País Economic Society in the municipality of Centro Habana. This is also the case of Escapando con el paisaje/Escaping with the landscape, at the Provincial Center of Plastic Arts and Design, curated by Elvia Rosa Castro and Sandra Montenegro, and a list of young artists whose proposals attempt to delve into a sarcastic game about the notion of escaping as a category, and the landscape as a subjective space.

By means of huge electrocardiograms made with the objects of all kind and arranged at the Servando Gallery, in El Vedado, Lidzie Alvisa made up Estados (States), a metaphor of existential matters that have a direct impact on the contemporary society. On the other hand, Wifredo Prieto chooses for his Circo Triste (Sad Circus) a 80 x 80 m space at the junction of J and Calzada streets, also located in the central neighborhood of El Vedado, where viewers will experience the feeling of hollowness when entering a 28 x 37 m big top, a place that usually conveys happiness, to find out that there is no show or public.

Another work inserted in public spaces in an organic manner is Alberto Matamoros and Claudia Echevarria’s Un caballo en La Habana (A horse in Havana), a mega sculpture with a gallery inside. It is located at the Cathedral Square in Old Havana. The invasive character of the content, resembling a huge Trojan Horse, is set by the impact of the artistic discourse on a given context. On his part, Rafael Villares proposes Paisaje Itinerante (Traveling Landscape) in which the artist moves around different areas of the city a piece of landscape built with natural elements.

In this year’s Biennial, like in previous editions, the concept of being Cuban is not limited to the geographic boundaries, it is expanded in order to track down and present the production of local artists living abroad. Thus, Adrian Melis will be in Havana as part of the You and You: Cartografías existenciales e Itinerarios urbanos en la era de la comunicación virtual (You and You: existential cartographies and urban itineraries in the era of virtual communication) collective exhibition curated by the cultural promoter of the Circus Project, Ada Azor, and curator and art critic Wendy Navarro, based in Spain. It is also worth mentioning the duet Atelier Morales (Juan Luis Morales and Teresa Ayuso) that propose Homenaje a Sakineh, Soraya, Amina y todas las otras (Homage to Sakineh, Soraya and all the others) in which by means of an “harmless” game box the artists seek to raise the audience’s awareness on the violence women are subjected to in several regions of the world under the official support of legal codes and laws.

The organization of the exhibitions has been marked by the lack of hierarchy in relation to the different forms of art and the horizontal approach to the museographic discourse, as well as by the possibility of generating spaces where different generations of artists coexist, from the most experienced to emerging creators. The side exhibitions represent a very particular overview of the island’s artistic development: we can identify in them names like Manuel Mendive, a loyal participant in every edition of the event, who brings this year the project Las Cabezas (The heads), an action involving more than seventy performers, among them dancers, musicians, singers, acrobats, jugglers, who will walk around the city for one day, adopting specific poses with their bodies painted by the artist.

Within the emerging artists is Hander Lara with El espacio de todas las cosas (The space of all things), who digs into the notion of place from different standpoints and in which dystopia, as a philosophical quality, is a constant element. There is also NielReyes, a young painter who carries out El acto y la sombra (The act and the shadow) a pictorial action created under the principle of “the expanded” trying to show the heterogeneity of the cultural life in a globalized world.

The side exhibition’s goal has always been to show not only the latest trends in art, but also the permanence of some topics and genres. Duvier del Dago’s Reencarnación (Reincarnation) is worth noting then; it is one of his typical installations made out of parts of real cannon collected by the artist at the Castillo del Morro. The work’s structure is made up of nylon and wood threads holding the pieces of the cannon in the air: reminiscences of a weapon re-contextualized in the artistic world. Likewise, we should mention Abstracción 2012 (Abstraction 2012), a project that systematizes and organizes this art expression in Cuba through a time line with names going from Antonio Vidal and Salvador Corratge, representatives of the artistic avant-garde of the 1950s, to contemporary figures like Rogel Tabares. Regarding the reinterpretation of the topics, there is Iliana Sanchez’s exhibition made up of twenty portraits produced under pop codes that suggests a different approach to this topic widely developed in the history of art.

A total of one hundred side projects add to the central exhibition; most of them showing the plural and nutritional character of the Cuban artistic panorama.