While delving into the history of 19th century’s Cuban painting, one of the most significant dates of all is January 1981. The Volume 1 exhibition –organized and curated by a group of young artists– was heralding a change in its approach to artistic creation. No wonder one of them, Tomas Sanchez (1948) had won the celebrated Joan Miro International Award the previous year with the drawing of a landscape. He eventually became one of the most outstanding figures in the realm of painting by the hand of his “Crucifixions”, his “Garbage Dumps” and above all, the gripping richness of his landscapes. Even though they had been preceded by the work of a painter from a previous generation, like Carlos Enriquez (1900-1957), the existence of a landscapists’ movement in our country was basically hinging on the styles and interests of those times.

While delving into the history of 19th century’s Cuban painting, one of the most significant dates of all is January 1981. The Volume 1 exhibition –organized and curated by a group of young artists– was heralding a change in its approach to artistic creation. No wonder one of them, Tomas Sanchez (1948) had won the celebrated Joan Miro International Award the previous year with the drawing of a landscape. He eventually became one of the most outstanding figures in the realm of painting by the hand of his “Crucifixions”, his “Garbage Dumps” and above all, the gripping richness of his landscapes. Even though they had been preceded by the work of a painter from a previous generation, like Carlos Enriquez (1900-1957), the existence of a landscapists’ movement in our country was basically hinging on the styles and interests of those times.

It’s necessary then to look back into Cuba’s landscape-painting movement in order to understand how much influence painters from different schools have had and still have in our visual panorama, as well as how landscape painting switched to a whole new signaling projection in the late 20th century. With no intention whatsoever to chart that particular line of expression, the names of Esteban Chartrand (1840-1883), Sanz Carta (1850-1898) and Fernandez Cavada (1831-1871) stand out in three landscape painting trends. Influenced respectively by the Barbizon School, the Spanish realism and the American realism portrayed in the landscapes of the Hudson River, these men came up with their own versions of the Cuban countryside at that time.

The academic principles would come over and over for decades, featuring some boldface names like Leopoldo Romañach (1862-1951) and Domingo Ramos (1894-1956), who for years insisted in a traditional version of our own rural areas.

Such tradition, whose repetition never turned it into a mere superfluous decoration –let’s remember the fan landscapes– and into tourist productions, was hurt deeply by the coming of the initial avant-gardism introduced by our artists beginning the 1930s. Thus, landscapes took down different paths, mostly the abovementioned countryside, with a major standout in the name of Enriquez, who wrote in 1943: “I’m drawn to human shape, landscapes and above all the combination of both because every man has his own inner or outer landscape he’ll never be able to stay away from.”1 A very different interest encouraged Ernesto Gonzalez Puig (1912-1988), who came back time and again with his imaginative and motley Island series.

There’s no doubt that when the term landscape is mentioned, the painted version of the land is what first comes to our minds. Suffice it to say that in various languages, that word alludes precisely to the ground scenery –landscape, paysage, landschaft, paisagem–, and so on. In different cultures, the land is seen and portrayed depending on the view –not only the sight– of the eye. That depends on the vision and the atmosphere that can be established with the spectator. A somewhat difficult perception of that communication is stated in the Buddhist teachings whereby nature, construed as the translation of the cosmic soul at its highest moments, portrays “the harmony of silence.” Echoes of that statement can be mentioned in the so-called Western conceptual world, with references to the reflections of a variety of painters engaged in achieving that “harmony.” For Theodore Rousseau, founder of the Barbizon Landscape School, the fluency of the air is “the model of infinity.” A century later, Tomas Sanchez, whose landscapes are painted under the halo of meditation and the encouraging richness of reflection, is pointedly in sync with the Hudson River painters because those “painted Nature as if it were a form of worshipping God.”

Such assortments made centuries apart and that have been briefly mentioned herein, lay bare the deep-rooted elaboration layer of thoughts and creeds that wreaks havoc with plain rationale; they scour cultures and times too distant apart in which, however, there’s a common thread in time and distance. Nature’s space and wonder are offered to those who want to see: the painter splays his experience on a piece of canvas, while the spectator has the opportunity to join him with his or her own emotive reading of the painted scene.

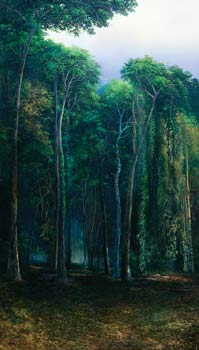

An approach that provides certain common points with these affirmations comes out in the words of Ania Toledo (1957) when she wrote in 2007, for the catalog of an individual exhibit, that “nature is the thing I believe in the most. It’s there where I see the image of the Christ of all of us. Feeling its presence by staring at daybreaks is also a way to notice that there are no boundaries dividing poetry, painting and life.” At that moment, Toledo sometimes resorts to the use of a huge cross within which she paints highly complex landscapes, some of them interrupted and dominated by a waterfall of crystal-clear water whose squeaky-clean clarity soothes the deep foliage of the trees, the vines and the shrubs.

This stage of Toledo’s landscape painting is marked by a very particular use of the chromatic hues. Highlighting the counterpoint of black and white, the blue shades both colorize and underscore the inner beat the whole scene is moved by. The clean areas are all clustered in the horizon which is now and then touched by some watery elements. That could either be a waterfall labeled as “Blessed Waters,” or just a clear zone that reflects the heavy trunks of the trees, as in “Sunrise,” or maybe has a much larger size on the canvas, like in “Ideal Space.” In other artworks ruled by the same style, such as “Rivulet,” she runs across the composition in a bid to convey the clarity in one corner of the composition all the way to its demise right down the opposite lower end. In “Spiritual Green,” the luminosity of the calm waters reflects the trunks of some of the trees, while it establishes a continuum with that clearness in the open space of the forest. In “Permanence,” on the contrary, the water melts into the shadows of the lush vegetation and is eventually shortened by the clear clouds up in the sky. It’s significant that these oils are part of the Landscape as Being series she exposed in late 2002. But that same resource is found in the Landscapes Forever series organized a couple of years later.

I must mention here some of the titles, many of them particularly interesting, handpicked by this artist from Cabaiguan. A few standouts are “Unity,” “Serene Farewell,” “Renaissance,” and above all, “Prelude.” “Morning Ceremony” and “Quiet Pool” are part of her insistence in the water-serenity-clarity resource that gives way and underlines the conception of these landscapes.

I must mention here some of the titles, many of them particularly interesting, handpicked by this artist from Cabaiguan. A few standouts are “Unity,” “Serene Farewell,” “Renaissance,” and above all, “Prelude.” “Morning Ceremony” and “Quiet Pool” are part of her insistence in the water-serenity-clarity resource that gives way and underlines the conception of these landscapes.

In “Splendorous Origin,” “The Luminous Fall,” “A Waterfall Evocation,” “Blessed Waters,” water itself derives into a fall of crystal-clear stream that dominates and, at the same time, echoes the bright sky. Thus, water is the main character of her landscapes, either in the form of ponds or pools, quiet and clean, or just as a waterfall that cuts through the lavish foliage and rolls all the way down with some mighty strength.

Last but not least, I’d like to refer to other elements that accentuate Ania Toledo’s landscapes. Clarity is centerpiece when it comes to handling a shadowy shade reflected by meditation and seen in each and every piece. You can feel the artist’s empathy when gazing at the landscape just to become a part of it. The innermost part of herself, the evocation of her feelings –until that moment submerged– are called upon and talked to their senses as we walk, by the hand of the painter, into a landscape brimming with a multitude of meanings.

Quite recently –back in 2007– Toledo becomes more present in her landscapes. In “It’s You” (from the Resurrection series), for instance, there’s a female body in the foreground that could perfectly be the artist herself. Standing, she’s turned her back to us since she’s also staring at –and being a part of– the reflexes in the still water and the tall trees that, nevertheless, do not make the force of her silhouette dwindle. The addition of this figure with her back turned to us has been a relatively frequent element in landscape painting overall. But even though in some cases its role is the establishment of a spatial relationship, being the “pool dreamer,” or just a tool to showcase the social character of that piece of countryside, in the case I’m addressing here it plays a very different role. I feel it’s just another element that, in Ania Toledo’s paintbrushes, invites us to join her and let her take us by the hand into the untapped countryside, perhaps in an effort to make us a part of that feeling that goes far beyond the mere and pleasant contemplation of a painted canvas.

Notes

1 In a letter sent to Alfred H. Barr, 1943, quoted in my book Paisaje con figuras, Union, 2005, page 19.