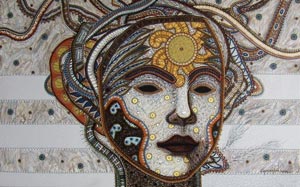

Anthological exhibitions lead, by necessity, to critical reviews; therefore in respect to Mímesis(Mimesis), a few words are required in regards to the aesthetic proposals of Manuel Lopez Oliva. Twenty years of artistic production are combined in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Museum of Fine Arts), in which the mask becomes an iconographic and poetic motif whose beginnings date back to the series Dioses, Semidioses y Mortales(Gods, Demigods and Mortals, 1992) and were exhibited for the first time at Sin Catálogo(Without Catalog, Wifredo Lam Center, 1993). This title serves as an intellectual provocation: the use of representation, with its inherent tradition in art’s precincts, functions in clear disjunctive with the conceptual spirit of the works, since Lopez Oliva’s reasons primarily do not attempt to grasp reality, but rather suggest and recreate it. Their masks are transmuted, associated with a plurality of artistic motivations, offering a wide repertoire of feelings and interpretations: sensuality, eroticism, reflection, sensory, etc.. The mask, in its symbolic dimension, stands as an iconographic reference in the artist’s inexhaustible creative act, turning them into the visual and philosophical motifs through which he comprehends and questions human existence.

Critical thinking’s sedimentation in regards to Manuel Lopez Oliva’s work of has led to the enunciation of collectively accepted aesthetic coordinates, that have been well summarized by Carina Pino-Santos: “Manuel Lopez Oliva’s painting, perhaps the best educated artist of his generation, uncovers an abundance of meanings through its constant references to allegories such as masquerade, theater and desire; overlapping baroque notions from other arts that the creator re-contextualizes according to the insular panorama, but always in a very dense manner [ ...]”.[i]

A statement of the vast knowledge system asserted by the artist, the search for a signic plurality in his works, and the persistent thematic-iconographic motives (the already mentioned masks and theatricality), together to a Baroque morphology, inevitably compromise critical interpretations of his visual proposal. Each of these topics, although addressed in several interviews, still requires the emergence of appraisal texts with a decoding will.

A statement of the vast knowledge system asserted by the artist, the search for a signic plurality in his works, and the persistent thematic-iconographic motives (the already mentioned masks and theatricality), together to a Baroque morphology, inevitably compromise critical interpretations of his visual proposal. Each of these topics, although addressed in several interviews, still requires the emergence of appraisal texts with a decoding will.

The Caribbean and the Carnival have been the ultimate stages for the mask in its cultural and symbolic dimension; from its primary meaning as an attribute, a component of an outfit or costume, up to its allegory of cultural resistance in the region. Visuality together with the components of these festivities: popular characters, costumes, games, among other group practices, have become themes for the region’s art; as well as an avenue for cultural inquiry into identity values and their collective significance. The confluence of rituals of Catholic, African and Indian heritage, authentic rhythms such as calypso andsteel band, or the costumes of different materials and shapes, turn the carnival into a thropos of Caribbean culture, which in the words of Norman Girvan, may be interpreted: “[...] as a vehicle to celebrate: freedom, social protest and cultural reaffirmation”.[ii]

Masks have become an art motif of great significance; that of collective freedom, fostered by the festivities, attributed to interpretations related to cultural cross-dressing or as attributes to conceal underlying truths. In its first function, social roles may be switched and transgressed legitimately, while in the second function which embodies the Caribbean man’s mutations, which had to be disputed amid the cultural model marked by the metropolis and products generated in the depths of hybridizations and mixed ancestry. Symbol apprehension contrasts result significant, in which colonial world order moves to the field of other interpretations.

In turn, the mask is also conceived as an allegory of cultural resistance. The intrinsic duality associated with the carrier and its essence of ambiguity or facade, encourages a philosophical and literary model of understanding of the components of regional Caribbean identity. Man takes possession of a set of attributable or imposed cultural signs, which he voluntarily or involuntarily uses or discards, but nevertheless from him. The duality between masks and skins, between black and white become a founding notion of creating a culture.

The masquerade then generates two ways of understanding such a fundamental phenomenon of Caribbean culture: as the value of eventual freedom or as an identity component. In this respect Yvonne Muñiz rightly suggested: “Mirrors and masks revolve in ambiguity, in encounters and disagreements, in reconciliations and challenges, on a board of constant definitions”.[iii]Dealt with sporadically in Cuban art, masks and their representations take center stage in López Oliva, and reflect an issue scantly addressed in the island’s contemporary panorama. In his proposals, the Caribbean and its masks are shown from the philosophical perception of human essence, from the ontological metaphor, because as the artist himself said: “[...] reality is also a carnival and a theater”.[iv]The mask does not imply the spaces’ incidental nature of openness or liberation, but acquires a permanent will of existence and everyday life; therefore, inherent to man. His characters do not only wear them, they also interact or discard them.

Man ponders amongst facades, according to social roles and life expression. The mask becomes essential, more than ornamental, and is perceived through the prism of he who assumes it as a cultural expression. “In my case, my paintings do not have masks, rather the faces themselves are masks; and I think it is mystery, uncertainty, adventure, passion and also hypocrisy, the most damaging of the human species”.[v]

Man ponders amongst facades, according to social roles and life expression. The mask becomes essential, more than ornamental, and is perceived through the prism of he who assumes it as a cultural expression. “In my case, my paintings do not have masks, rather the faces themselves are masks; and I think it is mystery, uncertainty, adventure, passion and also hypocrisy, the most damaging of the human species”.[v]

The self-referential perspective becomes an important analytical coordinate: his childhood experience, the duality artist-critic or family ties are expressed as a cannibalistic attitude. His world does not revolve around his work, but is represented in it. “I was born and played in a paint shop where all type of work was done: signs, floats and carnival masks”.[vi]The codes of music, theater and film complement a circuit of expressive references and concerns recognized by the artist himself in several articles and interviews. The vivacious atmosphere of his works, in debt with an internal artistic movement, indicates the presence of resources of a strong cinematographic nature: the importance of the shots (as in the case of Fuenteovejuna), the repetition of artistic motifs to resemble film strips, the succession of images, among others.

Regresión(Regression) is perhaps the most explicit work in this sense, precisely since it was conceived for a curatorial project that brought together the proposals of Cuban artists and the young filmography of the International Film School of San Antonio de los Baños. The image projected by the machine as an expression of female thought or memory, appeals directly to the means of cinema. Debts between man and technology, the translation of ideas by machines and the diversity of creative results represent the everyday images of the film industry by means of artistic resources.

In this film-natured sequence of images lies a continuous creative engine of internal rhythm and atmospheric sensation of compositions. The reiteration of ovals, lines, dots, suns or circles are a design exercise as support of complex shapes in imperative dynamism. The rhythm implies creative essence rather than a mere formal resort; it translates the vibrations and sinuosities of extensions that are caught in the faces and bodies, or simply fly freely in the air; becoming the pictorial scene’s drama. The reiteration of figurative elements resembles the rhythmic cadence of hidden music or a ritual drum’s regular tap, which become the artistic translation of Rabelais “sound islands”.

Theater’s significance in López Oliva’s work, often highlighted and honored as the newest creative period, evolves in its representation modes of and travels from symbol to sign. While in the first pieces devoted to this theatrical vocation appeared stages, backdrops, curtains and characters as contextualizing elements, over time the composition was simplified to focus on the man or the actor. Lopez gradually abandons the need to represent theater components, in order to emphasize tragic or epic human drama. Backgrounds lose prominence; the composition is simplified and figures are enlarged. El Pinocho(Pinocchio, 1993), becomes Brand: the curtain hands over its prominence to the character, the artistic interest shifts from space to face.

Even though the artist in his paintings purifies the expression codes, his concerns are enlarged in search of the most diverse media, with an emphatic tendency to incorporate real space to his works of art. Whether from the performance, public art or installations, López Oliva translates a basic principle of his activity as a critic: making art accessible to different audiences. In this regard, some of the most representative projects were completed during the Tenth Havana Biennial (2009): the Performance Combinatorio(Combinatorial Performance), in Las Carolinas theater-hall and Retrátese con Arte at the Casa de la FEU at the University of Havana. But while genre experimentation is a constant in Cuban art since the eighties, in Manuel Lopez Oliva the poetics of displacement take place.

The dual and complementary vocation as an artist and art critic has led to permanent transitions of: role, perspectives and approaches to art. According to the artist himself: “I have a cultural background that leads me to think in a polyhedral manner and my work is also polyhedral”.[vii]The abstraction capacity to understand processes, visual dynamics and poetics of figures or generations, in dialogue with the transgressions of postmodern art, determines the platform of this “(de)generated” artist, as he amusingly calls himself. And the impossibility of classification in all fields, this attachment to multiple roles within the art circuit, reinforces the disturbing transitions of the legitimated dialogue between center and periphery. López Oliva’s production since the nineties, I believe, corresponds to the artistic postulates’ period of utmost resolve and to creative proposals that even today still show the way.

The dual and complementary vocation as an artist and art critic has led to permanent transitions of: role, perspectives and approaches to art. According to the artist himself: “I have a cultural background that leads me to think in a polyhedral manner and my work is also polyhedral”.[vii]The abstraction capacity to understand processes, visual dynamics and poetics of figures or generations, in dialogue with the transgressions of postmodern art, determines the platform of this “(de)generated” artist, as he amusingly calls himself. And the impossibility of classification in all fields, this attachment to multiple roles within the art circuit, reinforces the disturbing transitions of the legitimated dialogue between center and periphery. López Oliva’s production since the nineties, I believe, corresponds to the artistic postulates’ period of utmost resolve and to creative proposals that even today still show the way.

The art critic and artist reveal his aesthetic thinking as a product of cultural and life interbreeding, of the hybridity that his roots and his academic formation have fostered. As Alejo Carpentier said “[...] Caribbean soil is the first theater of symbiosis, the first ever recorded encounter between three races, which as such, had never met: Whites of Europe, Indians of America, which were a complete novelty, and Africans [...]”.[viii]

López Oliva, as an individual, recognizes his ancient indigenous heritage, while Cuban and “a man of the world”, being consequent with José Martí’s ideals of “Nuestra America”. The complex human dimension is expressed as a vital and artistic result. In transculturation lies the essence of his work, creating a unique product that draws on multiple cultural matrixes: the West with its classical past, the Caribbean with its hybrid essence and Latin America with its native origins.

“I do not fear hybrid results, combinatorial – suggests the artist–, because I come from a heterogeneous national idiosyncrasy (Carpentier, Lezama Lima and other thinkers have called it ´Baroque´) and because life experience has made of me a hybrid personality too”.[ix]

The arts transgress its borders in the López Oliva’s work: theater, music and film overlap and translate randomly into artistic resources and on diverse media. The human body, ceramics, canvas, cardboard and cloth compete in order to take possession of the space. The masquerade becomes a form of individual expression associated with roles and human attitudes, not an advocate of reading for enjoyment and of release spaces, but rather as a vital condition of the individual, as a way of expressing feelings, attitudes and identities.

The category of thropos becomes an essential notion: carnival, mask or theater turn into components of multiple signical associations and philosophical reconsiderations. I clearly remember the dialogue regarding the work Antígonaand the inherent irony in the artist’s explanation: the classic female character is depicted with eyes that are unable to see. Antígona, while a defender of justice in Sophocles’ tragedy, is interpreted through the artistic exercise as sightless, due either to the weight of the tragic legacy of Oedipus or to the contemporary redefinition of human values.

The work indicates, in turn, the poetics of the complement (if it could exist theoretically), in the intertextual appropriation value of everything valid as art motif, as artistic resource or as a conceptual assumption. The creator is completed by the critic and vice versa, the mask with the face, the man with the stage, the philosopher with the communicator, the classic world with the contemporary world. The complementary pairs, acting simultaneously, express themselves through images and words.

Caribbean conflicts latently underlie in the “melting pot” of their creative concerns, either from the theoretical assumptions of their hybrid nature or from the privileged iconographic motifs. Its ethical principles and cultural scholar status can be summarized in the words of Alejo Carpentier, when he states: “The Caribbean is a splendid reality and its common fate leaves no doubt about it. Taking awareness of Caribbean reality expands and completes the Cuban identity’s conscience [...]”.[x]Manuel Lopez Oliva’s expressive paths –master with an eternal pupil attitude–, have found unusual ways and motivations in the history of Cuban art, which in turn serve as doors of a Caribbean cultural constellation. Theater and carnival as themes, the masks’ iconographic motifs and the artistic compositions’ implicit rhythm, draw cultural bridges between islands; weave the senses of a culture whose highest expression lies in the subject himself and a multitude of shades and contrasts.

Havana, June 3, 2010

[i] CARINA PINO SANTOS: “Finale of the tenth Edition of the Havana Biennial and Manuel López Oliva’s Performance”. http://www.lajiribilla.co.cu/2009/n417_05/417_07.html

[ii] NORMAN GIRVAN: “The carnival: developing its power.” http://www.acs-aec.org/columna/index23.htm.

[iii] IVONNE MUÑIZ: “On the contemporary Caribbean being. Subjectivity and representative iconographic bodies.” In Anales del Caribe, Havana, 2003, p. 13.

[iv] Excerpt from the interview with Daynet Rodriguez Sotomayor by Cubasí

[v] Ibídem.

[vi] Ibídem.

[vii] Ibídem.

[viii] ALEJO CARPENTIER:”The culture of the peoples living in the Caribbean Sea.” Anales del Caribe, Havana, No. 1, 1981, p. 200.

[ix] JORGE BERMÚDEZ: “About cathedrals and masks.” In Opus Habana, Vol III, No. 1, 1999, pp. 40-47.

[x] ALEJO CARPENTIER, Op cit., p. 206.

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022