“I don’t mind if being Latin American favors or damages my visibility”

Liliana Porter (1941) shoots with the effectiveness of a haiku through simple operations, with clean images and common objects placed in absurd or paradoxical situations. The Argentinean artist is one of the names to be mentioned when it comes to tackling the Latin American contemporary art; especially her young contributions are very interesting, since she was one of the few acclaimed female artists in that time. Based in New York since 1964, she founded in 1965 –along with Luis Camnitzer, her husband, and Jose Guillermo Castillo– the New York Graphic Workshop, engraving workshop and key operation center for the development of conceptual art. Ever since, she says, her work deals with the same topic. She has created, through drawings, engraving, photography, painting, video, brief staging or installations, even interventions in public spaces, a poetic and politic repertoire targeting the deceitful and inapprehensible experience represented by the reality.

The precociousness in her biography is amazing: when she was 17 years old, Porter was already good at engraving techniques and had studied art in Buenos Aires and Mexico City, and landed at the age of 22 in a city that was flourishing as the epicenter of world art. She recognizes that she was still thinking of Paris. But the meeting with other young artists, who were also Latin American and had just arrived in, triggered one of the most important chapters in the history of art during the 20th century. From the laboratory represented by the New YorkGW, they proved that the engraving had many more possibilities than the technical dexterity, starting to radicalize it and conceptualize it through new strategies, materials and ways of thinking about art.

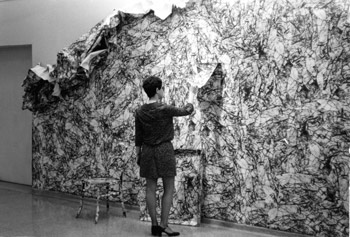

Liliana tells us more about that foundational moment: "We reconsidered and analyzed our ideas, our own work and the engraver role from the engraving context. The criticism and self-criticism took us to conclusions that modified our production and stimulated new ideas. The dialogue and communication established among us was very interesting, since the three of us had different worlds and productions, thus enriching the exchange. We placed emphasis on the ideas, which had to do with individual poetics, politic positions, concerns on different matters. In my case, I began working in settings, using offset printed papers. I also carried out mail exhibitions and installations by using serigraphy directly printed on the wall. I had a recurrent concern on the representation, the limit between the object and its image. I worked with shadows, wrinkles and empty space”.

Porter referred to time changes, the representation a how the reality "is one second, one image, one world, one book or nothing ". Just like the postcard of a landscape, which in the following images is detached from the surface by the own hand and what’s exhibited is its photographic registry (Arno, 1968). Or in Arruga (1968), a series of photoengraving where a neatly extended paper, looks –picture after picture– more and more crumpled.

From those representational games, the artist was making up a production that was showcased in 1973 –a solo exhibition– at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was awarded in the Engraving Biennial of Cali, Colombia. During the 1980s, she began to include inanimate objects, toys and figures in her narrations, a cast of characters that became a mark, playing the leading roles in staging or theater vignettes with great oneiric content. It was a ship at the beginning, she reminds, since the topic of travels was also recurrent in her work. Afterwards, as years passed by, she has collected several figures presented as minuscule beings that face the immensity of the picture, a huge space.

"I use this repertoire to set what I call 'situations'. I’m interested in the dialogues among dissimilar characters, which come from different times and ‘physicalities’ (if this word even exists); making simultaneous times that are apparently contradictory. When things converge and coexist, I find attractive situations. These reflections on the sense and substance of what we call reality, are constant elements in my work ", she reaffirms.

Porter experiments with small and large scales, with different systems and levels of representation, with figure, color and emptiness, with the spot and the line. Quotes of art history, literature, painting and engraving as languages are constantly discovered along with that feeling of humor and anguish caused by images located between the ludic and the sinister, the beauty and the concept, the triviality and possibility of meaning.

Porter experiments with small and large scales, with different systems and levels of representation, with figure, color and emptiness, with the spot and the line. Quotes of art history, literature, painting and engraving as languages are constantly discovered along with that feeling of humor and anguish caused by images located between the ludic and the sinister, the beauty and the concept, the triviality and possibility of meaning.

These are objects that gain a double existence, she explains: “They are mere appearance, unsubstantial ornaments and, at the same time, they have a look that can be animated by the spectators, capable of giving them an inner world and identity... This cast of figures and things has recently been enriched. I find them in markets, antique shops and some unusual places such as airports. I believe that I’m interested in those that seem to be confused”.

Liliana Porter’s work gives light to a new reality, where space, time and observers can coexist; what we see with what we imagine and remember.

FROM New York TO BUENOS AIRES

As she reaches the 50th anniversary of her artistic career, Porter has gained special prestige due to her participation in events such as the Biennial of Mercosur (Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2007), exhibition The New York Graphic Workshop: 1964-1970 (The Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, 2008), the Biennial of Sharjah (United Arab Emirates, 2009), and an exhibition of Reina Sofia National Museum and Art Center’s collection, Spain (2011-2012), space that acquired Arruga Instalacion Ambiente I (1969) in 2010, a montage with offset-printed paper sheets that partially cover one wall and have wrinkled edges.

From New York, she usually travels to Latin America: "I’m tied to my city, Buenos Aires; I visit it and regularly exhibit my work there. I’m also linked to Mexico, since my brother and nieces live there. I’ve recently carried out an exhibition at Tamayo Museum. The showcase was commissioned by Tobias Ostrander. On the other hand, I exhibited in Brazil some time ago, at Luciana Brito’s Gallery in San Pablo; as well as in Peru, Colombia, Uruguay and Costa Rica. My work has been showcased in Cuba, Chile and Venezuela”.

The calendar for this year is intense: she had a solo exhibition in March at Barbara Krakow Galley (Boston) and Sicardi Gallery (Houston); in May, she’s going to be exhibiting at Baginski Gallery in Lisbon, Portugal; in July, at YPF space in Buenos Aires; in September, at Spain’s Cultural Center in Santiago, Chile; and July and August 2013 will have her showcasing at the Latin American Museum of Art in Buenos Aires (MALBA).

Most of the artworks exhibited in these spaces have been recently created. The experience at YPF is going to be –for the first time– in large scale and will be open to “new ways of expressing the matters I’m interested in”.

The artist gives some details on the proposal: “The building and the place are big and my idea is staging a tour of visual events that will be placed on a circular platform. The spectators will be able to go through it and assemble their own narrative. Some of my recurrent characters are going to be present, the series of forced labor, and the cast, among others. I haven’t made my mind yet, but it all comes from two experiences I had, one at Museum MAD (Museum of Arts and Design) in New York, where I exhibited Man with Axe, a character that was carrying an axe and breaking small things until he faced others of bigger size, everything takes places on a white platform (perhaps a metaphor of time). Afterwards, I showcased a bigger version during my last exhibition at Hosfelt Gallery in New York. I doubled the size. The one I’m looking forward to showing at YPF space won’t be exactly the same topic of the man with an axe, or I might include it, but the dimensions are going to be bigger. I’m interested in this challenge and I like the idea of small-scaled characters in a huge space”.

The artist gives some details on the proposal: “The building and the place are big and my idea is staging a tour of visual events that will be placed on a circular platform. The spectators will be able to go through it and assemble their own narrative. Some of my recurrent characters are going to be present, the series of forced labor, and the cast, among others. I haven’t made my mind yet, but it all comes from two experiences I had, one at Museum MAD (Museum of Arts and Design) in New York, where I exhibited Man with Axe, a character that was carrying an axe and breaking small things until he faced others of bigger size, everything takes places on a white platform (perhaps a metaphor of time). Afterwards, I showcased a bigger version during my last exhibition at Hosfelt Gallery in New York. I doubled the size. The one I’m looking forward to showing at YPF space won’t be exactly the same topic of the man with an axe, or I might include it, but the dimensions are going to be bigger. I’m interested in this challenge and I like the idea of small-scaled characters in a huge space”.

Liliana reaffirms that her topics are the same “and what changes is the material or the cast. I’m always interested in facing new challenges." That was how –in the late 1990s– the artist produced a series of videos in which she explored her scenes with other narrative, including the time to capture minimum actions, when sometimes it seems like there nothing going on and, nevertheless, an imminent change is felt. The camera can also capture exhaustive details of these small toys. The perplexed is magnified, but they weirdly become more human; personal resonances keep us among the own memories, the memory and the comprehension of a destiny. For you (1999), Drum Solo (2000), Fox in the mirror (2007) and Matinee (2009), were also acquired by Reina Sofia Museum of Madrid. For these works, Porter counted on the collaboration of three Uruguayan artists: Ana Tiscornia, Marco Maggi and Sylvia Meyer.

THE OTHER

Thinking of the intrinsic relation between contemporary art and context, how do you connect your visual reflections on the reality with the imperialism of market and the show that affects us, or the extreme social differences in Latin America?

I believe that the reflections brought about by my series Trabajos forzados, in which the character faces situations that surpass him in scale and possibilities; or the topics in Disguise, in which somebody wants to be another person; or the “corrections”, when you innocently try to correct, for example, a doodle when conceptually a doodle is always right, or “fix” something, just as if you know what perfection is; or the series of dialogues among different beings or the portraits of the cast that gather at the same time different characters: the Nazi, the dancer, Che, the altar boy, historic characters from the present and past, expensive collection objects and others that are plastic and massively produced, etc. That simultaneity keeps its moral and speaks about all those essential matters and that questions that generate what’s called “the work”, and I think that, in different ways, they tackle those situations included in your question.

I believe that the reflections brought about by my series Trabajos forzados, in which the character faces situations that surpass him in scale and possibilities; or the topics in Disguise, in which somebody wants to be another person; or the “corrections”, when you innocently try to correct, for example, a doodle when conceptually a doodle is always right, or “fix” something, just as if you know what perfection is; or the series of dialogues among different beings or the portraits of the cast that gather at the same time different characters: the Nazi, the dancer, Che, the altar boy, historic characters from the present and past, expensive collection objects and others that are plastic and massively produced, etc. That simultaneity keeps its moral and speaks about all those essential matters and that questions that generate what’s called “the work”, and I think that, in different ways, they tackle those situations included in your question.

How were the first steps of an Argentinean artist (or Latin American) in New York? Was it too hard? How did you gain space there, as well as in the international stage?

For a young artist, New York in 1964 was something like entering a party. Many artists from different countries arrived in the city and there was a lot to see, experiment and learn. Within the New YorkGW, the group generated lots of ideas and work. We were invited to exhibit and participated and promoted many events in New York, as well as in Europe and Latin America. We were happy and worked within a stimulating context.

Ever since, what has been the artistic dialogue with Luis Camnitzer?

This is a very special moment, touching I would say, when we see that there is growing interest in the works and ideas from our youth. Luis and I are represented with those first artworks in many museums, institutions and private collections. Some months ago, I rebuilt for Reina Sofia Museum an environmental work I had created back in 1969 at the Museum of Modern Art in Caracas, Venezuela (Arruga Instalacion Ambiente I). We have a continuous dialogue with Luis, and we’re excited for having surpassed the 70 years!

Was your work influenced by the fact of your being Latin American or living in New York? Did it affect your relation with the stage?

The fact of my being Latin American is what defines my identity, the benchmark to perceive everything. I speak English with certain accent and I still think in Spanish, so it obviously has some influence in my life and my artistic production. I think that the fact of having lived in New York since I was 22 years old must have had a reflection in my experiences with this culture, which also makes up what I am now. My relation with “the stage" flows in a natural way and follows the perception possibilities of this world. I mean, there are two realities: the way I keep a relation with the environment and its relation with me. The "Hispanic" category, for example, isn’t my invention; it’s linked to readings made about us from the exterior. I establish my own reality without taking in the experiences offered by this culture and this environment. I feel that having a “foreign" perspective is somehow enriching.

How do you think the Latin American art is perceived in a cultural metropolis like New York?

It’s still perceived as “The Other”.

A sort of otherness, isn’t it? Do you think that it favors or damages your visibility and circulation in the local and international stage?

Frankly, I don’t care if being Latin American favors or damages my personal visibility. I’m not worried about it. What I’m interested is in trying to be more clear in my work and proposals, and if I succeed in contributing in something or generating in somebody (Latin American or not) any new thought, I will consider myself lucky. The context provisionally draws our appearances. I’m aware of it. Nobody is essentially local or foreigner, young or old, beautiful or ugly. The context produces a metamorphosis in the perceptions and appearances. What’s important for me is being coherent with myself and establishing a positive and happy relationship with “the other”. Ah! And that “international” art thing is an invention that doesn’t presently exist. Unless you think that the world is made up of just the bunch of countries shown in magazines.

How do Latin American artists that have migrated to New York, looking for better opportunities, face a so-complex context, a so-crowded scene, diverse and with opportunities for just a few?

How do Latin American artists that have migrated to New York, looking for better opportunities, face a so-complex context, a so-crowded scene, diverse and with opportunities for just a few?

Every people established a personal relation with the environment according to specific goals. You get to understand how the other feels you and take positions. There are some artists that in their need for "integrating the system” decide to start “thinking in English”, who don’t want to be identified with the culture of their homeland. It isn’t so in my case, I love living in New York and I can say, so far, that it has been and still is an extraordinary experience, but I‘m still emotionally linked to Latin America and I don’t feel like I have to choose sides or “integrate”. I think that I can be an Argentinean living in New York and I can tell you that I have had and have several opportunities to exhibit my work, I’ve a professor in this country for many years and I feel that I’ve received and have had the privilege of being able to give and contribute with this culture.

How is your work valued in the international art market?

Ah! I don’t know! You’ll have to ask the collectors....

You’re always present in fairs and biennials... What do you make of the art market in Latin America?

Since art fairs have played the leading role in cultural phenomenon, I’ve attended many of them with the galleries that represent me. As for the market of art, I can’t give an opinion about it. This is not my cup of tea, really.

Do you think that you work is currently more present in collections than it was before?

I can say that my work is exhibited in institutions, museums and private collections in Latin America, Europe and United States, and now comes to my mind that a Chinese collector also bought some of my work during a fair in that country.

What do you make of the Latin American art and the sort of boom existing in the international stage and market (felt in fairs like Pinta –New York and London– and acclaimed names, such as Teresa Margolles, Alfredo Jaar, Francis Alÿs…)?

I don’t know if that boom actually exists. We shouldn’t mythicize that much. Although there is certain opening for foreign artists in the local stage. Pinta, I guess, is a fair in which most of the buyers speak Spanish. Some Latin American artists don’t want to participate in Pinta; I think that they don’t like the fact of all attendees speaking Spanish.

Certain opening to foreign artists in New York? Why do you that situation have come up?

I believe that it has been the result of several factors. On the one hand, the claim and work of Latin American people to obtain the visibility they deserve in art. Mari Carmen Ramirez in Houston is one of the examples of a person that fights for it. On the other hand, the economic support provided by collectors and experts like Patricia Cisneros or Estrellita Brodsky, who promoted in institutions such as MoMA, TATE Gallery or Pompidou, opening policies for Latin American art. Finally, the economic situation in Latin America has readjusted the balance in the art market.