EthnotopIa: Preliminary Definition

Ethnotopia isa strategy of artistic representation, based on the synergic articulation of elements regarding the way of living and the habitat of a specific human group, obtaining as a result an indissoluble image. Such strategy is grounded on the identification of the culture and territory, connecting the being (or the “possible existence”) of a community with its “location” in the space. Therefore, the ethnotopic representation is associated with the need for identity confirmation or with ontological quests that could be either personal or collective, and could be expressed by means of procedures or languages so different from each other like painting, sculpture, collage, installation and performance. This diversity of options enables addressing different approaches and authors willing to build a discourse, either allegorical or critical.

The Latin American visual culture is full of ethnotopic references that try to represent a metaphorical synthesis of the vernacular by putting together a sort of symbolic map of the continent. It is a fact that this series of images is often wrongly interpreted as a result of a substantial and definitive identity that has originated several reductionisms. Yet, those proposals pose an interesting challenge to the processes of creation and artistic reflection in the countries of the region. It’s about, no less, building a symbolic imaginary that, beyond any teleological judgment, is obviously unfinished and plural.

To be: Modern Forerunners

To be: Modern Forerunners

Thinkers like Manuel Gonzalez Prada (Peru, 1848-1918), Jose Vasconcelos (Mexico, 1862-1959) and Jose Enrique Rodo (Uruguay, 1871-1917) outline a preliminary notion of the physiognomy of the Latin American being, noting certain features characteristic of the ethnotopic model. Gonzalez Prada speaks about Indian-Americans that will free themselves by their own efforts rather than by humanizing their oppressors. Vasconcelos refers to the “cosmic race”, created out of the wit and blood of all the peoples. Rodo describes Ariel as an example of human integrity, unselfishness and charity that opposes the Caliban’s practical and selfish spirit. Each of these figures defines, according to the thinkers, the specific behavior, the continental name of the people, in opposition to the foreign cultures. From these perspectives, not only the human content is envisioned, but also the geographic coordinates it lives in. This was confirmed by Vasconcelos as he said: “It would do us good that Amazonas River were Brazilian, or Iberian, as well as the Orinoco and the Magdalena. With the resources of such areas, the richest of all in wealth of all kind, the synthesis race could consolidate its culture... Close to the river, Universopolis could be raised and from there all the prayers, the squads and the planes for spreading good news would come out.”[i] This is, no less, a place for the being, or more exactly, the emerging of the ethnotopic approach.

From the pictorial angle, the ethnotopic approach is expressed in two levels: the iconographic, by combining anthropomorphic, vegetal and zoomorphic elements; and the space, by canceling out the gap between the figure and the bottom or mixing those components organically to create a visual continuity. Body and space are blended, claiming for its much-needed complementation. The Mexican murals, the Brazilian cannibalistic movement, indigenous and Creole expressions provide testimony of the rich mixture within individuals and their territory, of the carnal overlapping Latin America’s vast and rugged geography.

In La jungla (The Jungle, 1943) by Cuban Wifredo Lam, perhaps the most overwhelming and unquestionable example of ethnotopia, the natural and the human are almost the same thing. There are also tridimensional variants of the ethnotopic approach as it happens in Criolla (1936) by Venezuelan sculptor Francisco Narvaez. The wooden sculpture of a voluptuous woman with unmistakable mixed-race features rises soundly without changing the organic character of the block. The piece is crowned by a bunch of bananas that are almost confused with the woman’s hair, showing this deeply-rooted blend of figure and nature. It’s like if the work brought up to stage, at least in a suggestive manner, a piece of landscape.

In these proposals, as in almost every ethnotopia, time stops. The figures and the bodies remain in constant synchrony, in an eternal genesis. There is no genealogy, but a protohistoric amalgamation that is –at the same time– origin and destination. The artistic image is not penetrated by future developments as it happens in Bajtin’s cronotopo[ii]. Consequently, the work is not seen as a representation or an illustration of an account, but as the original instant of any fable; as the moment of the foundation.

Visual Ethnotopia as Collage

Visual Ethnotopia as Collage

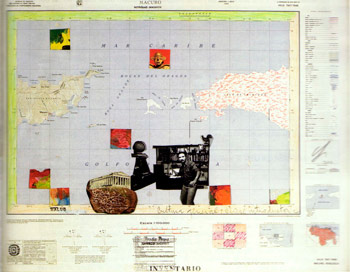

Visual ethnotopia has its contemporary declinations as well, based on the technical and iconographic artful devices and using collage as a strategy for creative articulation. Among the best examples of artists that put new life into this orientation is Venezuelan Claudio Perna (Milan, Italy, 1938-Holguin, Cuba, 1997), whose work centered on the art-ecology binomial. “I found out –he said– that there is no difference between the geographic and artistic postulates.”[iii] As a university professor of Geography and creator he said to be interested in the convergence of nature, life and creation. To him “nature’s resources, along with the resource of collective intelligence, generate landscape expressions...”[iv] This indissoluble relation between the individuals and the environment dominates his maps intervened with photos, drawings and notes. His works are thought up from the standpoint of a Cultural Geographer[v]who seeks to go deep into the “being in situation” that is both unique and plural. “I work –he says– with the human, conceptual and geographic convergence.”[vi] That’s why his maps of Venezuela, although do showing specific places, are full of multiple cultural references, both local and foreign, combining personal and collective, past and present, natural and urban allusions. The individual as protagonist: the territory as projection of the experience.

Perna’s work is not, plainly speaking, neither portraits nor landscapes; it doesn’t contain expressive or atmospheric effects either, which usually distinguish those genres. It actually consists of evocative, elliptical proposals that provide a more current ethnotopic approach, based in the physiognomic and space-related research: “Venezuela as a big territorial unit composed of multiple physical and cultural realities, of inhabitants and activities, of perceptions, of treasures that bear witness to the continuity of ideas.”[vii]

Instead of looking for the proportion between the map and the territory, between the physical and the abstract space, Claudio Perna’s proposal aims at establishing the human and cultural meaning of geography. In line with this concept, the collage is not only a technical procedure, but also a way to make the most of fragments and access diversity beyond the univocal character of the objective judgment. Bearing this in mind, the artist takes a closer look into the epistemology of complexity, according to which the world, which depends on our perceptions, does not matches a predefined and invariable reality, but one shaped by experience.

Ethnotopic performance

Ethnotopic performance

Having analyzed, up to here, the different nuances the ethnotopic approach has acquired as a strategy of representation linked to the subject and the environment, it is time to comment on the way this concept is related with the experience of the body and physical landscape. In this sense, performance art comes out as a new possibility of connection or vital reunion with the territory. Here, the approach, as in the Merleau-Pontiano perception model, becomes action and space, an extension of the body.

Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta (Havana, 1948-New York, 1985) turns that communion will between nature and body into an emblem, by means of her very personal approach of performance. “Big part of her work - Gerardo Mosquera wrote– consists of a unique act: to merge into the natural environment. She described it as follows: ‘I have thrown myself into the same elements that produced me, using the land as my canvas and my soul as my tools’.”[viii]

As a complement to the former statement, Mendieta became interested in finding out the cultural meaning of her actions, trying to go beyond, metaphorically speaking, gender and exile restrictions. That’s the reason why she introduced allusions to different cultures, particularly pre-Hispanic tradition and the Cuban-African liturgy. From them she took the sacred character of the land, rivers and the countryside. Delving into those elements, the artist seeks to reestablish the connection with a past and a culture that she considered essential.

In Siluetas (Silhouettes), a series of actions and interventions carried out in far-off sites of Iowa (US) and Oaxaca (Mexico) between 1973 and 1980, the artist’s figure is embedded in the landscape by means of natural materials like water, fire, mud, feathers, sand and gunpowder; she also used her own blood and hair: “the making up of the different silhouettes was methodically and accurately planned with a very detailed sketch, and carefully selecting the site and materials to be used. The latter were collected by Mendieta in sites she considered to have an inherited force, like archeological excavations in Mexico or the Nile’s riverbanks. With this, she planted another culture into her own, in the same way she had been transplanted from Cuba to the United States.”[ix]

After making Siluetas, Ana M. produced a series of sculptures in the caves of Jaruco (Cuba, 1981). In those works, the female shape emerges from the limestone with a marked archaic tone, showing her will to commune with the nature and culture of her birth country. During the pre-colonial times, the caves of Jaruco were inhabited by native people, and later served as shelter to the rebels of the independence movement. As a result, working in this site was an act of psychological compensation and anthropological reaffirmations that symbolizes, in its broader sense, the return to the origins.

Mendieta’s creative itinerary was relatively short, but intense and loaded with geographical anthropological connotations. “Ana used herself as a metaphor. And even her tragic death seemed to have completed the cycle –in a horrifying logic– in her last work. As a sign of the utopia and impossibility of her project, her last silhouette was stamped on the cement of New York, going back to her first performances with death and blood.”[x] Even with her fatal resolution, this proposal seals to its full extent the evolution and the final destination of the ethnotopic approach in Latin America,[xi] which seeks no more than the perfect fusion of the subject and the territory through art.

Final remarks (A few warnings)

Final remarks (A few warnings)

Fate decreed that the examples used to support these reflections are exclusively of Venezuelan and Cuban creators from the 20th century. However, the common points we have found in these artists do not discard the geo-cultural elements that distinguish the two nations. The different space configuration the two peoples inhabit is obvious. Continentality on one hand; insularity on the other, without disregarding though that the two of them are part of the same sea basin: the Caribbean.

So, if we have taken them as examples of a hypothesis that influenced the continental plastic art, it’s because their work, in addition to be widely known in the intellectual circles of the region, has become a model. Obviously, there are other artists in the hemisphere that fall within the proposed approach, being particularly important Brazilian Tarsila Do Amaral’s cannibal oneiric, Uruguayan Pedro Figari’s overwhelming scenes, and Chilean Juan Downey’s ethnographic videos , just to mention a few.

Another noteworthy aspect is that this article, as opposed to what one might think, doesn’t try to define “the Latin American” neither to establish its identity, but to analyze the peculiarities of the ethnotopic approach as a “strategy of artistic representation. “This is the reason why we just describe the procedure and its relation with the artists’ poetics, without judging the level of pertinence or objectivity with which creators handle the ethnotopic representation.

Caracas, December 2011

[i]JOSE VASCONCELOS: “La raza cósmica”, 1925. Quoted by LEOPOLDO ZEA, Latin American philosophy and culture. National Council of Culture, Romulo Gallegos Center for Latin American Studies, Caracas, 1976, p. 48.

[ii]MijailBajtinapplies the term cronotopo to the theory of literature, defining it as “...the combination of special and time elements in an incomprehensible and well-defined whole. Time is condensed here, is compressed, becomes visible from the artistic point of view; while space is intensified, penetrates in the movement of time (...) the time elements are revealed in the space, and the space is seen and measured through time. The intersection of the series and junctions of these elements is the main feature of the artistic cronotopo.” See Bajtin, Mijail. The forms and cronotopo in novels. Essays on historic poetics. In Theory and aesthetic of novels. Madrid, Taurus, 1989 pp. 237-409.

[iii]ClaudioPerna. Quoted in MARIA ELENA RAMOS: “Arte, idea, geografia”. In: NOI. Nuevo Orden Informativo. N°1, Caracas, February 17, 1991 (without pages).

[iv]Idem.

[v]ZULEIVA VIVAS: “Claudio Perna y el arte del pensamiento”. In: RevistaEstilomagazine. Year 7, N°29, Caracas, Nov. 1996, p. 34.

[vi]CLAUDIO PERNA: “Algunas palabras a manera de de esclarecimiento”. En: NOI. Nuevo Orden Informativo. Op. Cit.

[vii]Claudio Perna. Quoted in MARIA ELENA RAMOS: “Arte, idea, geografía”. Op. Cit.

[viii]GERARDOMOSQUERA: “Arte, Religión y Diferencia Cultural”. In: http://www.replica21.com/archivo/m_n/37_mosquera_mendieta.html

[ix]StinaBarchan. The poetic silhouettes of Ana Mendieta (Translation into Spanish Anahi Escobar). Konstvetenskap vid Lunds Universited.

[x]GERARDO MOSQUERA: “Arte, Religión y Diferencia Cultural”. Op. Cit.

[xi]It is important to note that in AnaMendieta’s work there is a point in which the relation between the being and the territory, almost absolutely consubstantiate, transcends the boundaries of the ethnotopic approach to open to temporality. In Ana both the body and the matter and space are exposed to the happening, the change, corrosion…This is the beginning of a chapter dealing with historicity as the expiry ritual. A matter that requires a reflection framework broader than the one proposed here.