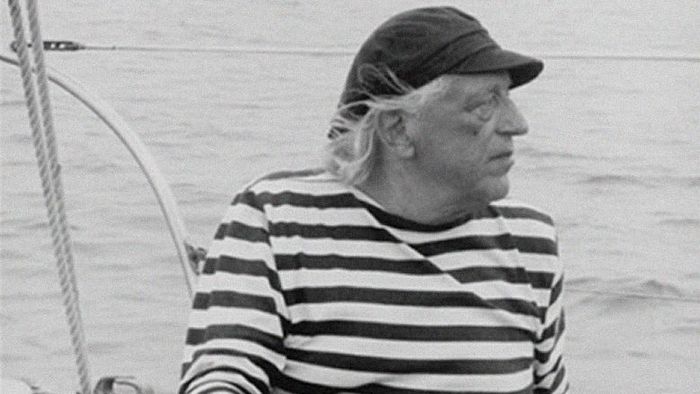

Luis Camnitzer (1937) is not only critical of and wily about his artistic work, but also of and about his writing, an aspect he’s developed along the past 40 years and that speaks volumes –something that probably also happens in his pedagogical career– of a coherent thinking based on his condition as a Latin American “avant-garde,” “internationalized” artist. Camnitzer mulls over the situation of art in a variety of processes ranging from colonialism and the expansion of the market economy to the globalization process. In the face of adverse panoramas, he always waves the banner of the thoughtful and acting artist.

This German-origin Uruguayan has lived in New York since 1964. Within the left-wing intelligentsia of that time and as one of the founding fathers of conceptualism, he became a source of reference in the moving of engraving to installation, in a “political” art and a visual work that relies on words. Camnitzer is one of the greatest exponents of Latin America’s contemporary art. Recognized by the mainstream –despite the fact that labels himself as a “revolutionary artist,” he hinges on that paradoxical experience to come up with a comprehensive work that melts, from its very first (mis)understandings into one of the world’s art epicenters. And it’s on this uncomfortable position that’s been twisting him around since then where he manages to put together ethics and esthetics. His condition of Latin American artist means to him an epitome of the contemporary artist who’s supposed to work in the global scene without turning his back on his own turf, warding off any possibility of exoticism and triviality.

In his visual work and essays, he reveals certain basic keys to understanding “periphery” art, both in the first decades of his career and today, when practices labeled as “Latin American” are highly coveted in the international scene and consumerism criteria seem to stain any art that’s critical of sensationalism and lack of political-social commitment.

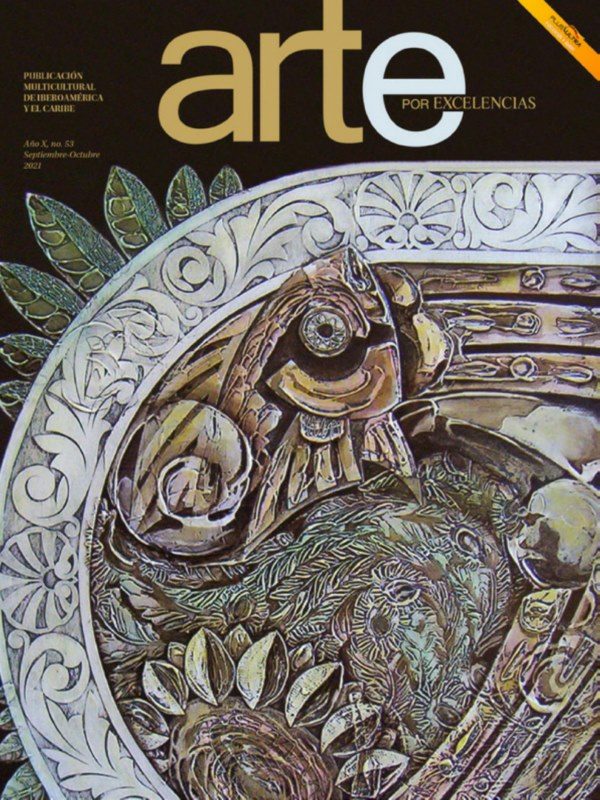

Under this conviction, the Metales Pesados publishing house and art theoretician Gonzalo Pedraza put out in Chile a compilation of eight texts (from 1969 to 2006), some of them related to lectures dictated in different places, and others to publication on websites or in newspapers. From Coca-Cola to Asshole Art serves as a new approach to the artist’s visual creation, but above all, to his reflections on the role of both the artist and the work, even touching on such fields as cultural review, politics and activism.

How could anyone stay put when hearing such phrases as “we live in the alienating myth that we’re, first of all, artists. We are not. We’re basically ethical beings who can tell right from wrong, fair from unfair, not only as individuals, but also as a community and a region […] Our definition of art, of what culture we serve, of what public we choose as audience, of what of our work must accomplish, are all political decisions.”

Pedraza’s selection stuck to the interest in “talking about art,” which in the case of Camnitzer –the Chilean expert writes in the forewords– leads to “a return to the individual and his experience.” Thus, it’s so motivating to find an autobiographical, enjoyable and colloquial tone of this lucid, “theoretical” writing intimately linked to life situations and, of course, to the creative work of an artist who never stops watching and thinking his context, who seeks the ways to put across his message rather than letting it rest in the white box of the gallery or on the museum pedestal.

The book was also conceived as a contribution to the local context, as this young theoretician explains:

Camnitzer shares with us the condition of looking at a dominant cultural knot, that is, he’s ingrained in our own sizing of the so-called “colonial relationship.” In today’s Chile, we’re living an international openness as never before –the result of the enclosure provided by the dictatorship’s cultural blackout and the transformation of the art from antiestablishment to official– and it’s developing at a white-heat pace into a tricky web of hopes and validations of the centers, things all that Camnitzer chews over, criticizes and dismantles. This publication is an attempt to put his experience on our side, like a whisper of what could possibly happen if we fail to take actions and precautions.

Even though the center-periphery notions are under fire today, it’s good to turn back to the first texts written by an artist who endured in his own flesh the clash between the colony and the empire, and who promoted an “esthetics of change” through the prism of the avant-garde utopia dealing with institutional confrontation as the “integration of esthetic creativeness to all the systems of reference in everyday’s life.”

As a visionary, in “Contemporary Colonial Art” (1969) he was already speaking of “international-style” cross-cultural processes and “borderless art,” armed with

the identity problems they imply and that become so visible today in the face of globalization. The name of the game is precisely the discovery of assertions from that time that remain as valid as ever, as when he lays bare the “paradox of artists full of political lucidity who work for the metropolitan culture.” Today, with all the changes that have come to pass from a polarized world to another one without walls, in which the “enemy” (the market and its allies: the mass media and the publicity machinery) has finally managed to co-opt every-

thing, where politically-lucid

artists sell and make the rounds in fairs and biennials, in the market of hegemonic items and ideas.

What are the chances of the contemporary artist’s resistance when he’s dealing with a foe without a face? Camnitzer speaks of “ethic cynicism,” of the possibility of being there, of “selling oneself” even with political lucidity; a relative frivolity that at least grants individual freedom. The irony is just another tool that refreshes and rocks in the reading of his texts.

Though the book leaps from 1969 to the 1980s, the tone of avant-garde manifesto continues with words nourished by life experience, armed with that delicate humor, even poetic and the nonstop reflection about those political, cultural and social processes. In “Access to Mainstream” (1987) and “The Wonder Pan and the Spanglish Art” (1988), he sinks lock, stock and barrel into the situation of critical art within the framework of the market and the possibility of fixing its homogenizing power from the art system itself: “The fact that the mainstream reaches out to us or passes us by is not what actually counts. The nitty-gritty issue here is our clinging to the building of a culture and our knowing as precisely as we possibly can what and whose that culture we’re building is.”

It’s not necessary to know Camnitzer’s work to digest this selection that points to the artist’s ethics in times of showbiz and market blitz. About “globalism” the author speaks as well, a new type of colonialism in terms of information management and the passiveness of those receiving that information. In this context, he describes the artist as “a meaning-maker per se,” underlining the importance of his work from a cultural meaning; and art –in a necessary 1970s style– as “ a combat weapon” in which subversion is a “useful tool to give society a new lease on life.”

He delves into this particular topic in “Coco-Cola’s Discreet Charm” (1998) and “The Foreigner’s Vision” (1999), honing his critical view on the mass media, publicity and expansion operation of such companies as Coca-Cola and McDonalds, boasting an exercise of content analysis and read-between-the-line assessments that reveal operations of “colonial globalism,” an intermediate status between traditional colonialism and real globalism. In the area of the arts, he unearths parallels in the multicultural strategists of both corporations and sponsors, concluding that “we have a tendency toward art denationalization, at least in terms of merchandise production. In the meantime, corporations blend into the frontiers and they are often even more powerful than the countries they are based in. They go usurping identities to later on move out to more convenient locations.” This also touches the right chord when it comes to critical, committed art as it is subdued by a trademark or trend.

Camnitzer’s texts also show cultural reflections in which his stances in the neo-avant-garde and the 1960s leftism, coupled with his condition as an international artist that grew stronger in the 1980s, whip his discourse into shape, a discourse that feedbacks and converges on certain idealisms. The artist doesn’t lose his sense of utopia of a beginning and holds on tight to the hope of cultural autonomy and construction in the face of those forces that render critical art worthless and leave the public trapped in ignorance and alienation caused by the ongoing system. He’s not either a diehard ideologue keen on past experiences. He’s an avid news reader, a web surfer who discoverers in hacker-activism a few parallels with the conceptualism of his origins. But he goes even farther: he sees in these practices –and in their development from an esthetic standpoint far beyond the influence of the “information warfare”– the possibility of reenergizing conceptual art from the power of resistance ad subversion in the face of emerging globalism.

Camnitzer underscores some key problems of the arts within the current context. He makes us wonder whatever happened to the “political art” of the 1960 and 70, why there’s so much silence and distance with the social trappings and the urgencies of our times, but without ever demonizing the market. Before this panorama, the “meaning-maker per se” must be clever in processing his own information and searching for new esthetic codes that match the cultural impact underneath the surface and onto the array of media-hyped images and practices. That’s what he broaches in “Toward a Theory of Asshole Art” (2006), in which he intends to outline an art –in Liliana Porter’s own words, quoted by him– “capable of that silence so perfect that will let us listen to utopistically. The asshole side would be the space of the contrary.” Between imbecility and invisibility, Camnitzer says, an art that denies its own essence without falling in the nonexistence groove, that in a bid to vanquish power and consumerism relations, “is luring information rather than giving it,” thus piquing the imagination.

To round up his appraisals on the art as a system, the artist speaks in the last text, “Art and State” (2006) about a key topic in emerging cultural institutions: the role played by the State in the face of the need to build identities and let artists work on them, free from the pressures of both the market and fashion. To him, cultural vitality does not depend on “the miracles of the private initiative” or “the somewhat thorny creation of the private foundations”. In the most mind-cleared nations, he adds, “it’s the government the one that acts as a foundation.”

Camnitzer’s coherence is surprising in comments that, at the end of the book, nearly quote to the letter the ideas of the past, and they sound even urgently today: “For me, the artist is primarily an ethic being or citizen, one who tells right from wrong… The policy of this is not a content… is the game of strategies to be used in order to reaffirm ethics,” thus firing away, among his many analyses and examples of cultural policies worldwide, such notions as this one: “The artist has to be standing behind the spectator and help him open up his eyes.”

Publicación anterior RODRIGO MOYA: THE INSURRECTIONAL IMAGE

Publicación siguiente LET’S COME CLOSER TO A (SO-CALLED) HAVANA HOUSE