After attending last year’s 53rd Venice Biennial, Ivan Navarro’s career has been undisputedly on the rise. This platform gave top international hype. Working with galleries in New York, Madrid, Paris and Sao Paolo, the Chilean artist has scheduled institutional exhibits till 2012. In 2009, he exhibited in several European cities and then moved on to the Cairo Biennial. This season he’s been making the rounds from north to south, across the Americas only to land in New Orleans for the Prospect 2 Biennial in November. With a ludicrous and analytical sense, his proposal is marked by the use of electric power and fluorescent tubes that twist the view of ordinary objects around. Between sculptures and installations, he runs through constructivism, minimalism and contemporary strategies, piquing both attending spectators and the power systems.

In Chile he’s stacked up against Alfredo Jaar: two artists born in this long and narrow strip of land located in the southern tip of the world that migrated to New York to achieve unsuspected pinnacles in their careers. With 16 years of differences in their ages –Jaar was born in 1956 and Navarro in 1972– the comparison could be kind of whimsical. It’s true that the younger artist shows off some reminiscences of the great Chilean creator: between the local and the global, we ferret out a work that equally comes up with a tad of flak in it; individuality that puts borders on the line, captivates outstanding platforms, eggs on curators and –more recently– makes headlines and cover stories in major magazines worldwide. Thus, we saw him this summer during the 131st edition of Arte Al Dia International and ArtNexus 77. Moreover, the latter event labeled his exposition in Venice –authored by Tatiana Flores, assistant professor of Art History at the University of Rutgers– as “a spectacular experience.”

Ivan Navarro grew up in the dictatorship and became an artist in 1991 and 1995, when Chile was just staging its comeback to democracy. In this context, he’s marked off some major differences with his antecessor who had migrated to the Big Apple in the 1980s, who’s been more than once at the Venice Biennial and who’s long since broken away from his homeland from a thematic standpoint. Navarro doesn’t stop looking to Chile. Or at least he doesn’t stop talking with his current history –that has clearly moved past him– and with other outstanding stakeholders. Here, he melts himself into a generation locally marked by the influx of the Advanced Scene –Egenio Dittborn, CADA Group and Gonzalo Diaz, among others– and by Chile’s post-dictatorial scenario. And that’s also the influx of teachings on engraving displacements passed on to him by master Eduardo Vilches at the Catholic University of Santiago, and the experiences of Luis Camnitzer back in the 1960s and 70s.

In this college he studied with other artists, like his elder brother Mario Navarro, Monica Bengoa, Carlos Navarrete and Francisca Garcia, among other, and all graduated in the early 1990s to meet a common formation circuit. This is a group that had to elbow its way through the contemporary art spaces that were opening up at the time, soon routed by benchmarking curators like Justo Pastor Mellado and Guillermo Machuca, among others.

In 1997, Navarro is already in New York. It was a three-month trip that made a difference with his fellow artists. From one of the epicenters of today’s arts, we now see him wallowing in the kind of recognition that keeps him working harder than ever before, still taking on the challenge of being an international Latin American artist.

The Great Lamp

How did you switch from engraving to strategies with objects and electricity?

I never switched from one thing to another. Since I started studying I kept both practices on separate ways. I also did photography on my own. What actually helped me cling to all those practices was the wiggle room provided by Ricardo Vilches to work with objects and installations, and with the serialization of engraving, something that’s fundamental for my generation.

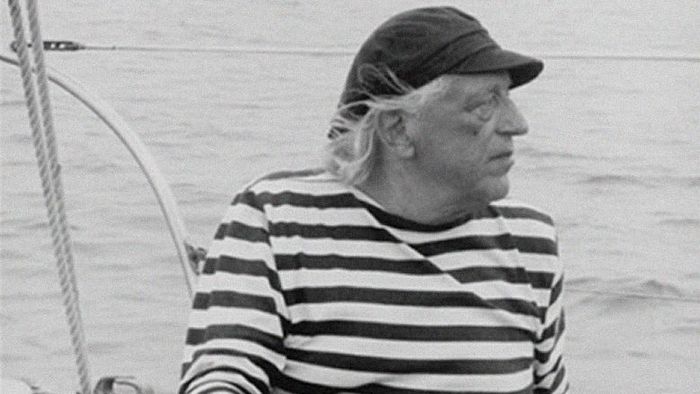

When he studied in college, Ivan Navarro started to draw a bead on light and body presence. It was a work parallel to academic teaching in which he used to photograph a bunch of albinos who went around asking for alms in his barrio. “They attracted me as characters affected by light, with no identity, with no skin color. They were like celestial beings that could suddenly show up… I used to photograph them in sorts of performances, painting their hairs and their eyes. I used to put them under the social situation,” he recalls. With a copy of this series he grabbed an honorary mention in the now gone Matisse Engraving Prize at the National Museum of Fine Arts. “It was something very important to me. The work title was “Trust my Neighbor.” It was a color photo, –taken by Polla Trujillo– the portrait of an albino I knew and me standing next to him, with the work title written with Letraset on the bottom end.”

The artist was 20 years old and that was the first milestone in his career. His work got a new lease on life. And he then started working with lamps and came up with a series of objects made of different materials to which electricity power was added and could be placed in the living room of a house or in an art gallery. Irony, ambiguity, the relationship between art and life were already whipping a production into shape, a production that found new boundaries. The Great Lamp (1996) is one big leap forward that changed the experience of exhibition space: at the then fledgling Gabriela Mistral Art Gallery, Navarro installed bulbs, sockets and electric power in a diagram that covered the walls and generated a lighted atmosphere and shadows. Other artworks from that time were placed as operational devices in which assembly was the strategy and precariousness stood for a kind of esthetics that could prevail over the anecdotic, moving past quotations of modernism and sending out an invitation for spectators to take a hands-on attitude: Satellite (1999), for instance, was installed at the now gone Posada del Corregidor Gallery by means of a tripod, a bicycle wheel, electric transformers, bulbs and hand-generated power.

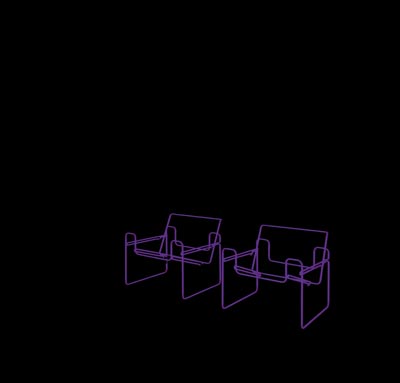

Since the early 2000s, his electric chairs captivated art galleries across New York. Made of fluorescent tubes and featuring explicit citations to the capital punishment that still remains in place in some states across the U.S. and to torture practices used during the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, the installations shed light on the contextual crossings that eventually nourished the creations that came after that. This is a proposal that conditioned the jump onto the world limelight, that opened up a new horizon to the global public and that prompted the appraisal of celebrated curators that have marked his career, like Dan Cameron, Rina Carvajal, Carolina Ponce de Leon and Anne Ellegood, among others.

Far from Chile, the artist was more evidently related from a thematic standpoint to the dictatorship’s existence, to a family history tainted by repression, exile, torture and missing people. But finding himself in similar situations in his country of residence, or at least in the face of social injustices, his ethical commitment to the problems of his own time exceeded the national frontiers. And this, coupled with his seduction skills, is exactly what the contemporary art system has paid heed to.

Way too far is the 25-year-old youngster who came to New York for three months and landed a job of fixing antique furniture in the Big Apple. Has it been too hard to move ahead in New York and onto the world scene –construed as fairs, biennials, art meetings, publications and curatorship? How did you make it?

Yes, it’s tough and I keep on working on that. It never stops. There’s no formula… it’s all sheer luck.

Where Are They?

In addition to developing his own personal work, Ivan Navarro works in collaboration with other Chilean artists, expanding the limits of his own work beyond other places. With some residents in New York –Ian Szydlowski and Diego Hernandez– he founded the Instituto Divorciado (Divorced Institute) that collaborates with artists and groups of artists at a world level. Together with songwriter Nutria NN, he launched the Hueso Records label. With his wife, American sculptor Courtney Smith, Navarro has added other artworks by sharing his interest with the crossing between art and design. Together with his brother Mario, Navarro has mounted exhibits and curatorial projects both in Chile and around the globe. And he’s also worked closely with artist and curator Camilo Yañez. One of the milestones of that twosome association was the mounting of Where Are They? (2008), that was exposed at the Matucana 100 Cultural Center and gave him an Altazor Prize in 2009, a recognition doled out in Chile to local artists in a number of artistic expressions.

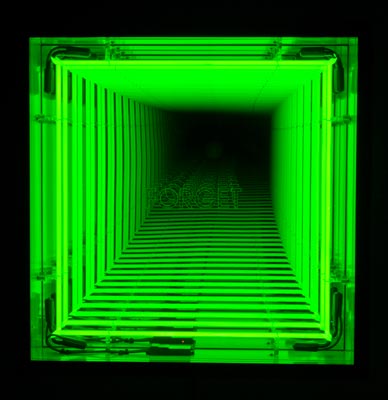

The installation engulfed a huge dark storehouse spectators could only walk in with the help of a flashlight, enough to light up a dark corridor that led to a couple of balconies that overlooked the floor and a humongous word puzzle. The hidden names in the puzzle belonged to people charged with human rights violations during the military regime.

Most of them have beaten the rap in court. Behind that sad game, the ambience took a reddish shade provided by fluorescent lights coming from a mirrored box tethered to the wall –on the rear side of the balconies- that projected its inner reflections toward infinity. The grand tour inside the installation was complemented by a publication containing dozens of names related to unpunished torture and assassination charges, including risible sentences given to some of the perpetrators.

The artworks he presented during the Venice Biennial were far more globalized. Under the title Threshold, Navarro was the only representative from the newly-opened Chile pavilion, an effort conducted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Cultural Affairs Division (DIRAC). In a 300-square-meter storehouse located in the La Cordonerie sector, next to the main exhibit by curator Daniel Birnbaum, there were pieces like Bed, a cylinder that projected the word bed on the floor; Resistance, a sculpture made of a bicycle and a chair with fluorescent tubes that could go on when someone pedaled the bi, plus a video of a man steering his own two-wheeler through NY’s Time Square; and Death Row, the centerpiece attraction consisting of a series of thirteen doors equipped with neon lights that followed a pattern similar to Bed, but submitting each threshold to an illusion of infinity, allusive in the same breath to Ellsworth Kelly’s Spectrum V (1969) with a similar chromatic order in its painted panels.

Beyond minimalism, the crossings between the politics and showbiz are inevitable. The glow of the neon lights, the perceptual tricks, ambiguity and the luring character of his objects –they draw sights and invite us to try them out beyond stark experimentation– take us to situations we easily find in our societies. From the ludicrous, quasi-childish experience we soon move on to the idea of exile, and perhaps to disorientation, vertigo and alienation.

What repercussions did Where Are They ever have?

We won the Altazor Prize, a public recognition. Not too many people are drawn to that piece and I think it was all owed to it that I was invited to represent Chile in Venice.

I tell you what happened with Where Are They? and if you want to comment on it, be my guest: the long line of people that stood outside to watch it on the opening day actually struck my attention, perhaps because there were expectations about Nutria’s presentation that was coming up next, everything seen from the perspective of a Chilean artist who makes it in New York and who was in Chile with a heck of a good piece… I didn’t see it that day because I was sick and tired of everyday lines to hop on the new Transantiago buses… Well, when I went to see it a few days later, I walked in all by myself and I felt that sense of crowdedness and showbiz was gone, with so many boldface names from the Chilean arts going in and out… The work was somewhat gripping and that darkness, that deathly hush that was shattered altogether by the ludicrous tone of the word puzzle… Indeed, I’ve got a question that could be related to that situation: do you think the critical, political sense of a piece doesn’t yield the same results when it makes rounds in the big scenes, basking in so much media hype and leaning to showbiz? Even when it’s put on sale, does it work the same?

I don’t know. A piece’s critical effect could be gauged in a second or 50 years later, it’s so relative. I wonder what you make of big scenes. Camilo (Yañez) thought there were few people that day at Matacuna 100. For him, it was not a crowded event that had gone out of hand. And there was not so much press either.

I read on a website (http://potq.cl/2007/12/25/%C2%BFdonde-estan-%E2%80%93-ivan-navarro/) that Admiral Hugo Cabezas Videla’s son was lashing out at you because you had included his father in the piece and for not abiding by the truth out of “artistic and pecuniary interests.” The admiral had played a role in saving detainees back in 1973 and he even died in very obscure circumstances. How did you take on this situation?

I had no idea about that situation. I clearly announced in the exposition catalog that I’d taken the information from the archives on memoriaviva.com to put together that piece (http://www.memoriaviva.com/culpables/criminales%20c/cabezas_videla_hugo.htm). (That website says: “The Funa Commission accused the following officers as responsible for the Valparaiso tortures after that military coup: Rear Admiral Hugo Cabezas Videla, Joint Chief of Staff…”). I extend my apologies to the Admiral’s son if the information on this website is misleading.

I Feel No Pain

Obviously, Ivan Navarro doesn’t go unnoticed when he arrives in Chile. A sort of homemade star system shrouds him without affecting his humbleness. I once had a long interview with him for the book Chile Extreme Art: A New Scene in the Turn of the Century[i]. It was back in 2005 and the success of the past year was not even in the artist’s wildest dreams. Now, in an emailed interview, his answers are equally short, straight to the point, sometimes unwanted, but always assertive and far from the conceptual demands or the sometimes whimsical straightforwardness coming from artists like Alfredo Jaar and Eugenio Dittborn, just another Chilean author widely recognized in the world scenario who never left Chile, though. Willing to collaborate, the feedback was immediate as he also opened up the dialogue to the ongoing situation in his country of origin, a nation that’s unveiling a new administration after twenty years under the rule of the Coordination of Parties for Democracy.

Do you believe there are common strategies and themes among Latin American artists on the world scene? I mean, in the sense that world-class spaces tend to privilege, for instance, the references to past dictatorships, to questions of identity within a globalized framework or to a certain sense of decadence in the field of showbiz, among just other recurrent problems? Are there common topics in the area that could shape up trends and make a difference in terms of contributions to the international scene?

I don’t know. It seems you can see more than I do. What you say belongs to the world around us and that exerts influence not only on the artists. I don’t think there are strategies for artistic success, but rather smart and hard work. Curators and gallery owners are ruled by completely subjective schemes when it comes to inviting artists to come up with projects. And that’s just another problem. The only strategy that ties me up to other international artists is the fact that I left my country of origin to work in New York.

But don’t you think your work has basked in the world limelight because it deals with topics that draw interest in Latin America, like the overlapping of political history (local) and showbiz, including references to the Chile dictatorship?

That’s a question I always ask myself. That’s why I question my work from different viewpoints… I work with curators and gallery owners with very different works in all of them. I can’t tell you my international success is owed to a specific kind of work. The (art) world is very large so as to determine that. It’s interesting to think that many artists from my generation don’t work on those topics and they’re faring pretty well.

How do you cope with your condition as a critical artist who’s into the mainstream that Camnitzer mentions in some of his texts, like the “Latin American internationalized avant-garde artist”, the “revolutionary” and yet mainstream-oriented artist?

Now the art world is too big and too impossible to dominate so as to define it so severely. It’s ridiculous to speak of “Latin American artists” at a time when national identities are under fire, when Camnitzer himself (Uruguayan) is of German origin and lives temporarily in New York. I don’t think his work is recognized by the mainstream either… He’s not part of the Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons circuits. That’s what mainstream is all about!

How has your life in New York determined both your work and your career?

It has helped me get a personal vision of my work. Everything is so peculiar in New York.

And your attending the Venice Biennial?

A complete success.

How do you measure the success of your attending that biennial? Is there something like a before and an after? That explains why you’ve been on the cover of two prestigious magazines on international art, Arte Al Dia and ArtNexus, doesn’t it? What do you make of that media hype?

It’s pretty rewarding to be recognized. My attending the Venice Biennial helped me in that respect. I also believe the public enjoyed that work very much too. That makes you assume it was successful. Now, a year after that event, I’ve got many proposals to come up with new projects with people who knew and appraised the work in Venice.

How has your work been changing in recent years?

It’s becoming increasingly hard to work because I’m very demanding with my job. That’s pretty bracketed right now and it’s hard to come up with new ideas in that field I’ve created myself.

How has your proposal changed as it becomes more international?

I make references to artists and situations that are not necessarily linked to the Chilean reality. That means a literal distance. Materially speaking, nothing has changed. Conceptually speaking, I keep doing the same things since I left Chile…

What projects are you working on right now?

I’ve been lately interested in researching on language quirks to turn them into sculptures. I want to move from 2D to 3D or perhaps to some kind of unknown dimension.

Do you mean works like Bed (2009) and Exodus (2008)? (They can be penciled in as part of a new object category in which word becomes structure; ambiguous, it’s repeated in a mirror game into the infinity, with its meaning dangling over a bottomless pit…).

I’m beginning to look up phrases… those words you’re telling me led me to what I’m researching right now. I’m interested in phrases that unwontedly get into a contradiction or kill themselves… something like “I feel no pain,” just an example…

What do you turn the object registry into, that registry that has populated your creations: the car, the bicycle, the chairs, the doors, the porches? What meaning do they convey?

I’m interested in working with metaphors on the functionality of art and their social usages, concepts I’ve taken from (Ludwig) Wittgenstein, (Jean) Baudrillard, (Gilles) Deleuze and (Roberto) Bolaño… How that functionality, obvious or literal, inquires the spectator is far deeper than the appearance of the everyday objects you mention. The pieces I do are analytical and not formal. They speak of sculpturing as a practice and certain social or political situations that have to do with sculptural or monumental ideas I like to criticize.

Tell me more about those concepts that hook up those philosophers with Chilean author Roberto Bolaño…

From each and every one of these authors I’ve extracted ideas that link closer to my ideas of how to understand sculpturing. From Wittgenstein I’m interested in the language quirks. From Baudrillard, I try to cotton on to the abstract form of the signs. From Deleuze, the rhizome, and from Bolaño, humor.

In your work there’s been a view that overlaps Chile’s political history, especially from the dictatorship, and the history of your country of residence. What about today’s Chile? Do you also stand your ground from the latest social, political and cultural changes occurred in tour country of origin?

The Where Are They? project addresses today’s Chile.

The following toys a bit with fiction: you’re one of the artists that grew during the 1990s, who started getting media hype and attention thanks to a local scene that contributes to the free market and also due to the cultural and institutional character that developed during the governments of the Coordination. Even your participation in the Venice Biennial was coordinated by the administration.

Do you believe you and the other artists that benefited from this context –Patrick Hamilton, Mario Navarro, Camilo Yañez, Claudio Correa, Monica Bengoa, among others– will have a similar relationship with Sebastian Piñera’s government? What do you it’d happen with the local art that has circulated under certain cultural policies, that experimental, critical art that marked a moment (the turn of the century) and that now shine internationally even under the intentions of a “country image”? Will there be a new visual orientation coming onstage?

I don’t know. I don’t want to think of that. I try to think of “that” Chile as less as possible. Cultural policies are entrapped… the Piñera Foundation didn’t help us in Matucana 100 to realize the Where Are They? Project, and they got very angry when we received the Altazor and my brother Mario –he went to pick up the prize for me because I wasn’t there- said publicly not to vote for Piñera… Anyway, art in Chile is decoration and that’s tremendously ironic and fosters experimentation…

What expectations do you have with the job of the new Minister of Culture, Luciano Cruz Coke?

None. I’m not aware of his job. I wish he could do something good for all Chileans.

[i]From authors Carolina Lara, Guillermo Machuca and Sergio Rojas. The research includes interviews with 20 major artists from the 90s generation that has circulated as a virtual book on the Web since 2005. In 2010, a new edition of the book was put out in Santiago de Chile by the Calabaza del Diablo (Devil’s Pumpkin) publishing house.