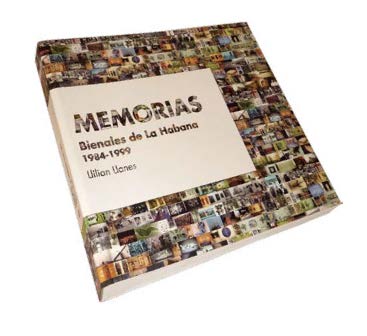

Amid the intense days of the Eleventh Havana Biennial, held in May and June this year, and which got the attention of several sectors of the public and critics, it was presented to the nation's capital the book Memoirs: Biennialsof Havana1984-1999,written by Lillian Llanes,who served during that period as the event’s director and also director of the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center.

Under the auspices of the Cuban Artimprint of the Plastic Arts National Council, the volume, with 347 pages and alarge amount of photographic illustrations, brings together individual and collective experiences of those who carried out "the most important of the Cuban cultural events arising during the pas tcentury”, according to what Isabel Perez, director of the Editorial, said in the prologue, to later assert that this is an event “whose contributions in the field of contemporary visual art go beyond the narrow confines of the Island (... ) to establish itself as one of the exemplary paradigms of what would become the international art biennials around the world(...)”.

From the first Biennale held in 1984 to the sixth held in 1999, the event moved through different experience’s degrees which built a social and cultural imaginary around the visual arts, regardless of expressions, techniques, formats and relationships with the Havana City scenario, which it was in fact converted not only in the great scenes from where the artists projected their works but, gradually, in undisputed part of the curatorial discourses that were continually reaffirming paths and perspectives of the artistic practices in our regions and elsewhere.

The Havana Biennial, from its modest position in a geographical-cultural non-centered space in the contemporary art’s mainstreams, was the first of many similar events in the world whose aesthetic fragmentations organically articulated themselves in creative speeches and territories that gave rise in the eighties to a kind of multicultural fever for the first time in the history of the so-called developed countries. From this small Caribbean island it was hatched the future plot of international art events, whose purposes would deal to show the visual richness of the Third World, ruled out for centuries by the famous elite corners of Europe and the United States of America. More than three-quarters of humanity were suddenly represented in a new scenario -Cuban, Caribbean, Latin American- fighting tenaciously for them to be visible despite the limited financial and logistics resources of art.

The Havana Biennial, from its modest position in a geographical-cultural non-centered space in the contemporary art’s mainstreams, was the first of many similar events in the world whose aesthetic fragmentations organically articulated themselves in creative speeches and territories that gave rise in the eighties to a kind of multicultural fever for the first time in the history of the so-called developed countries. From this small Caribbean island it was hatched the future plot of international art events, whose purposes would deal to show the visual richness of the Third World, ruled out for centuries by the famous elite corners of Europe and the United States of America. More than three-quarters of humanity were suddenly represented in a new scenario -Cuban, Caribbean, Latin American- fighting tenaciously for them to be visible despite the limited financial and logistics resources of art.

The first edition had such an impact in the global landscape that, from its very realization, the Havana Biennial attracted the attention of artists, journalists, collectors, institutions and intellectuals of almost the whole world who came to Cuba to show works, reflect, discuss, make creation workshops with the public and celebrate, in one way or another, the potential of the artistic expressions of such a lot of artists, many of which were discovered in a unanimous way from the second edition in 1986, when Africa, Asia and the Middle East were summoned, besides Latin America and the Caribbean. Some had trouble recognizing what has been achieved by the event, but there is no doubt that it worked this structure tested for the first time to articulate symbolic imaginaries from bookish and field investigations in many countries and regions ignored or undervalued

The same year of the third edition, 1989, France set out to organize an event with a similar trend, tempted by the magnitude and the expectations created by the Havana Biennial: I refer to the famous exhibition Les magicines de la Terre, curated by Jean Hubert Martin, whose undeniable resonance generated, years later, international recognition in forums and symposiums with the Havana Biennial, as they were considered as the most significant events of the decade. Undoubtedly that third edition condensed mega-exhibitions’ new model, because it started from a curatorial principle sufficiently closed and open at the same time, in whose essential nodules converged the crafts and applied arts, the most diverse expressions of popular culture, the architecture equal to painting, printmaking, sculpture, photography, objects, installations and new technologies.

For the author, the fourth edition consolidated the biennial at various levels, especially in more organized thematic exhibitions, an incipient spaces expansion to the East of the city (specifically in the ancient forts of El Morro and La Cabana, as up to that moment the Fine Arts National Museum had acted as the display center par excellence, plus the space support of other Cuban institutions) and a fierce presence of uninvited Cuban artists to the central body. And internally, the organization was carried out according to a defined responsibility from each of the team members that since the previous edition had appeared but not crystallized yet. The experience of study and research trips had paid off, particularly in areas well away geographically, and there were already a wealth of information that few art centers in the world had, which would be the undisputed platform of the future professional work of the curators and managers of production, assembly and promotion.

The fifth edition took to the foreground the importance of the curatorial team for making small and large decisions, from the selection of artists and experts who would form the basic structure of the Biennale, to the print design and the spreading scheme. According to Llilian Llanes "the accumulated knowledge allowed that it was finally established that method of collective work, which prevailed since then, based mainly in the pursuit of excellence...", giving special emphasis to the related work in the event’s economic sphere and in the international relationships, important pillars of what was achieved in 1994.

Five major nucleuses formed that Biennial exhibitions and a remarkable group of solo shows reaffirmed the mastery of several creators from the regions convened. Likewise the exhibit spaces in the historical center and the modern part of the city were diversified, despite the difficult conditions in which the event took place. As the author points out, "although there was always a lot of skepticism about the survival chances of the Havana Biennial, after the Fifth Biennial nobody believed it could continue to be held...", on the chapter dedicated to the last edition she directed, the Sixth in 1997.

There would be too many details to mention here regarding the vicissitudes experienced since the mid-nineties to celebrate editions of the Biennial, and that the author exposes in the respective introductions she makes to chapters, but the fact is that not a few thought the event (unlike others who have million dollars budgets in almost all the world, whether in Asia, in Europe or Latin America) would continue to hold its theoretical and conceptual budgets, its own structure in triad form (exhibitions, workshops and discussion forums) and its local and international projection on the basis of a few thousand dollars, other expenses in local currency and an increasingly scarce infrastructure of material support provided by local institutions and the Ministry of Culture. The country was fully entering into one of the toughest periods in its history from the economic point of view: the remarkable support given to the Biennial from the start was not the same, and it couldn’t be even if there were will and interest in reverting this situation.

The Sixth Biennial, convened on the basis of reflection on the role of memory in the individual and in society, essentially continued traveling for everything achieved in the previous editions, with bigger support from the local city government and from the City Historian’s Office in offering spaces. It once again tested the endurance, tenacity, courage, flexibility and intelligence of its director and curatorial team to overcome very complex work situations and a subtle sleight of the scope and significance of the event by the international media as well as surreptitious attitudes of curators and critics in the West, to whom the Havana Biennial created too many concerns, questions, fears, doubts, about their respective professional unfoldings. This was an unprecedented new phenomenon on the global scene of the art circuits, emerged and developed from a small Caribbean island that did not enjoy any more the intellectual backing experienced during the sixties.

Undoubtedly, the book Memoirs... results in a meticulous summary of the fortunes and misfortunes of who directed an event of this nature in complex conditions nationally, interwoven with an incredible inventory of anecdotes that attest to the almost countless avatars that the work team, specially curators, went through to carry out one of the most significant projects of Cuban culture in the second half of the twentieth century.

The book, "aimed primarily at young people", according to the wishes of the author, contains information related to the material, financial, promotional, and the organization and internal structure of the Biennial, mentioning several officials, institutions, personalities, places, travels, letters, visits, documents, minutes, numbers and figures that make up this journey through 15 years of intense activity in the individual and in the collective though, according to the author in her final remarks : "(...) there were undoubtedly many things untold but I think that the provided information is enough to evaluate the significance that the various editions of the Biennale may have had (...)".

Despite the large number of pages, effective works’ images and significant projects are no seen in the book, even though there are many works, especially from the fourth and fifth editions. May be the fact of not having high resolution photos (something so common now but not in those hard years of the mid-eighties and throughout the nineties) prevented to highlight extraordinary proposals from numerous artists, workshops and debate forums, which would have complemented the edition in a relevant way.

At the appendixes, over sixty pages at the end, the reader can find tables of participant artists, demonstrations and invited countries, conferences, selection of articles published by the national and foreign press and other data.

We hope that this authorial and editorial effort be seen, at the future, complemented with the publication of other memoirs that collect the successive Biennial editions since 2000, when it was held the Seventh. The experience continues with different curatorial and structural nuances due to a greater complexity of the local and international scene, and profound changes in each cultural context upon it acts, which makes the event an ever-changing and difficult challenge in each new edition. We also hope to count with people who dare to narrate it to their new and veteran main characters.

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022