At the Good Pastor Church in New York City, a mass was consecrated in memory of Belkis Ayon, at the request of Carole and Alex Rosenberg. During the mass, Bach music was played. The friends who had gathered there recounted their memories and celebrated the artist’s life. At the altar was Sikan con Chivo, the outstanding engraving that grabbed the top prize at the First International Graphic Biennial in Maastricht, the Netherlands, perhaps the most celebrated piece and the most remarkable icon left by Ayon.

Eulogy, Salutation, Speech, Narration, Prayer; Speak

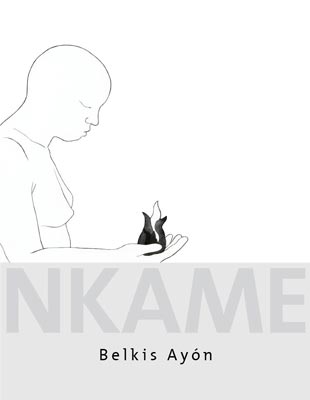

Before me lies Nkame, a thick volume, a catalog reasonably designed that contains Belkis Ayon’s work (Havana, 1967-1999) [The Rope and the Fire], a white female torso seen from the left profile right on the foreground; her open hand holds / delivers the fire.

What other book could be more anticipated than the one we hope it’s going to provide the keys to unraveling a mystery? The mystery of a work that could seem to be the result an anticipation, and the mystery of a demise that also came to pass way too soon.

The grandiose exhibition –no other adjective fits in any better– that back in 2009 took over the halls of the St. Francis of Assisi Convent in Old Havana, has now spun off this catalog, the result of the passionate, persistent and painstaking efforts of Belkis Ayon’s Estate, Dr. Katia Ayon –the project’s director general- and numerous team of experts, admirer and friends of the artist’s that includes Cuban researcher and curator Cristina Vives, a collaborator and friend of Belkis’, who laid out the publishing concept of the book, as well as Jose Veigas, a Cuban curator, researcher and critic who took the technical helm of the catalog.

According to the forewords, the book-catalog intends to thoroughly document Belkis Ayon’s life and work, to piece together the necessary elements for the study of the poetics, to chronologically show all the known work and goad gallery owners and researchers to count on an authentication and study tool beforehand. They have been bound to ward off a number of drawbacks along the way, like the lack of background information in Cuba in terms of this kind of compilation and the absence of experts in the field that would have culled catalogs of fine artists, with the sole exception of Wifredo Lam in Cuban Collections, by scholar Jose Manuel Noceda, that was put out in 2002 by the Wifredo Lam Center for Contemporary Art. That’s by far the only example that can be mentioned in our turf.

With this catalog in their hands, readers will notice the preciousness of the quests and the flexible application of technical guidelines a project like this calls for and that eventually produced a genuine gem. They will surely notice (feel) how the layout, the ordering of the entire material –both theoretical, testimonial and graphic- complies with a criterion of growth and densification that manages to touch us –and move us– as if we were inside a spiral, under the effects of a piercing music –Byzantium music, Abakua drums? The same heightened feeling this observer had a year ago as she traipsed through the halls of the St. Francis of Assisi Convent during the exhibition.

“The Consecration” –the first part of the volume– picks up three substantial, critical approaches: by Cristina Vives (“Her Own Voice”); by David Mateo (“Engraving as Resource and Determination”) and by Lazara Menendez (“To Discover Fear”).

“My Soul and I Love You”, the second part, brings in fourteen testimonials made by experts, collaborators, disciples, collectors and friends of the artist’s; “I Gave You the Power”, the third part, belongs to the catalog, while the fourth and fifth parts include a glossary, biographical information and iconography, plus additional material. The volume also features an addendum of texts translated into English.

Most of the bibliography registered up to now [I’m quoting Cristina Vives’ essay dated Oct. 2005, page 22], and it’s regrettable to admit this, recounts the legend, “translate” the myth only to identify it with her works following a long tour. / When the sedimentation of the myth happens in Belkis, through a proportional process alongside the sedimentation of her own personality; when the titles of Sikan(1991), Nlloro(1991), were followed by Let me Out(1997), Disobedience (1998), Stalking(1998), We Have to Be Patient(1998), the artist’s image had already been cast… like the die… and time had rolled on.

She accepted the “challenge ingrained in the possession of the esthetic-plastic and poetic resemblance of one of the elements of Cuban culture could actually be like.” [Lazara Menendez, page 71, quotes Ayon’s own remarks]. By doing this, she took the chance of approaching a development historically located in the marginality generated by cultural differences and transmuting it into a strategy and a fit of active emancipation by trying to legitimize a critical thinking capable of integrating different traditions and ways of looking at the world. The Abakua “powers” derive into a metaphor that forces us to give up on the autonomy the esthetic and the formal acquire in the West’s modern art.

These lines refer to the crux of the dilemma: receptivity and behavior of the specialized critics in the course of the artist’s lifespan and after. And it should be, one of the outstanding aspects of this book-catalog is precisely the attempt to work out those limitations, to foster in-depth elucidation, the theoretical support of the creative process and the scope of Belkis Ayon’s work.

For David Mateo, page 43:

Belkis’ work contributed to blow away that harmful dichotomy between engraving accepted as a trade or as an artistic resource, and in her creation the verification of a series of technical particularities that lead to thinking of a before and an after of her persona in the application of the method in Cuba.

The book-catalog is a publishing work in which superb heed to the sense must be paid, taking advantage of space and adequately harmonizing both texts and graphics. It’s an admirable joint effort by its editor, poet Alex Fleites and designer Laura Llopiz. But these words won’t be good enough to describe the delivery of this genuine work of art that nourishes itself and pays tribute to the work it was born for.

What’s left then? Open up the book and find in it what Belkis Ayon appears to announce in her own voice (page 56): “I create images for the most varied stories of the myth, driven by its lessons on human inquiry, on the struggle for conservation and survival, on the symbolic coincidences and the meaningfulness in other cultures so distant in space and time.”

Open the book that, as a matter of fact, is now a privileged concert performed by many hands and many hearts. Let’s see –with Adelaida de Juan, page 208): “the eyes shine, fixed on the face, with a dazzling white that downplays our attention and deciphering ability.”

Old Havana, Nov. 2, 2010

Nkame. Belkis Ayón, Turner Editores, Madrid, 2010.