In the show “Smoke and Mirrors – A Revue in Picture,” Stephan Dillemuth (*1954 Büdingen, lives in Munich) presents newly conceived and site-specific works, as well as older works from the 1980s as contrast. His complex oeuvre encompasses painting, sculpture, video, and installation. This will be the first time so many of his pieces will be on display together in an institution.

Visitors will be greeted even before they enter the Künstlerhaus. From the yew tree at the main entrance twitters Dillemuth’s “Vogellieder an der Jahrhundert- wende” (Birdsong at the turn of the century, 1998). These birdsongs—composed of around eighty spoken samples of various names of artists from that era—are a kind of homage.

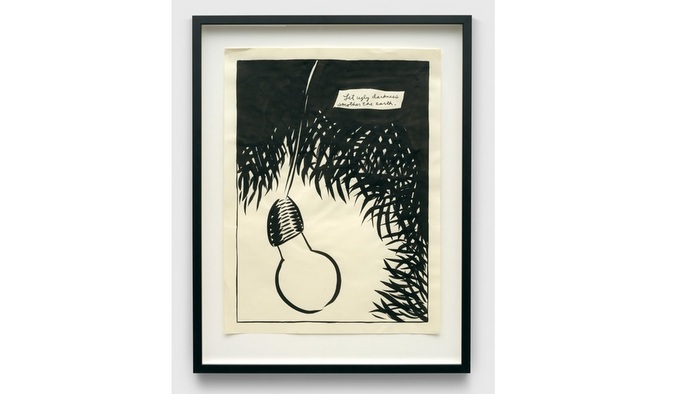

Visitors enter the exhibition as if they were going through a time machine of sorts—two large canvases feature infinity clocks that point to three-thirty. In the main exhibition hall, this impression is reinforced by the reflection of the glass ceiling in the floor. Like a view of a walk-in display case, the revue can be experienced from a variety of angles. Colorful body parts hang from the ceiling, but it’s only by looking at them from one specific standpoint that viewers see the image of an entire human body. Other works of art also deal with the principle of fragmentation. Dillemuth doesn’t really use his collaged, plaster-cast body parts as a self-portrait, but as more of a cipher or code—and as raw material for making new objects. Some human body parts are supplemented by animal components, such as boars’ heads, cattle ears, and deer feet, and tied together with cogs. This results in hybrid creatures that can also be read as psychological figurations. These newer works of art, which resemble a description of the human condition in the financial crisis, are commented upon by Dillemuth’s earlier works.

The first “Bayernbilder” (Bavaria paintings) were produced in 1979, when he was still at the art academy in Düsseldorf. The visual source materials were sentimental postcard motifs from Bavarian spa towns. The painting style is suited to the theme—neither expressive, nor wild, but rather unintentional and trivial. Nevertheless, by elevating the postcard to a painting, Dillemuth’s work remains critical of art—for, after all, it’s also about the political attitude in the way that the medium as such clings to tradition.

In the more than fifty-part “Schönheitsgalerie” (Gallery of beauty, 1985) Dillemuth explores questions about representation. A collector of portraits of beautiful women, Bavaria’s King Ludwig I insisted that beauty was separate from status and social class. Thus, the portraits of aristocratic and bourgeois beauties hung next to each other in an egalitarian way. Dillemuth’s gallery, however, turns against the idea of external beauty and how it is represented in art. The paintings, like the faces, develop a life of their own through the process of painting, which makes it possible to see a new kind of “beauty,” if it is indeed true that art and beauty are equivalent.

From the beauties to excess, from the Nymphenburg Palace to the nightclub—in the apse of the Künstlerhaus we will see works that are being shown for the first time, even though they were produced in the late 1980s in Chicago. The wall objects, which resemble disco decorations, glitter in the projector light of the “Portfolio Robot”—a dancing pedestal. The video “Happy Hours” (1988) is of an exhibition piece; seven looped, Super 8 projections revolve amid the sound of acid house music. Is disco a Theater of Cruelty—a place where all images, whether ugly or beautiful, mean or seductive, are transcendent in ecstasy or intensity?

In showing his new works—and now, in connection with his works from the 1980s—Dillemuth creates a new way of presenting his oeuvre, in which he acts like a theatrical designer, setting up new, site-specific scenes that have a certain theatricality, as well as an alluring effect. Again and again, questions arise about the role of the artist in society and the artistic means employed in his practice. For Dillemuth, art has the potential not only to reflect upon social changes, but to trigger them, as well. Through research, reflection, analysis, and experimentation, limitations, conventions, and taboos can be explored and also transcended, if necessary. So it’s completely desirable if visitors to the show are reminded of an experiment that poses questions and ideas.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue featuring essays by Helmut Draxler, Kerstin Stakemeier, and Stephan Dillemuth. In addition, Dillemuth has an extensive website: http://societyofcontrol.com.

Stephan Dillemuth studied at the art academies in Nuremberg, Düsseldorf, and Munich. He currently teaches at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich.

From 1990 to 1994 Dillemuth, Josef Strau, Nils Norman, Merlin Carpenter, and Kiron Khosla operated the space Friesenwall 120 in Cologne, then UTV (Unser Fernsehsender mit / Our television channel with Hans Christian Dany). In 1995 there was the Summer Academy at the Kunstverein Munich and the publications “AKADEMIE” and “The Academy and the Corporate Public.” Starting in 1997, his collaboration with Werner von Delmont resulted in various performances and the publication “Corporate Rokoko.” Since 2000, he’s had solo projects at locales such as Galerie Nagel Draxler (Cologne/Berlin), American Fine Art (New York), Galerie für Landschaftskunst (Hamburg), Reena Spaulings (New York), Galerie Éric Hussenot (Paris), Secession (Vienna), Konsthall C (Stockholm), Transmission Gallery (Glasgow), and Uma Certa Falta de Coerencia (Porto).

22-04- 11-06-2017

Stephan Dillemuth

Sound and Smoke – a Revue in Pictures

Lecture by Kerstin Stakemeier: 30.05.2017, 6 pm

Artist Talk & Film Screening: 08.06.2017, 6 pm

Catalogue in progress

curated by Sandro Droschl

Related Publications

Museo del Prado | Juan Muñoz. Stories of Art

January 07, 2026

Musée national Picasso-Paris. Raymond Pettibon. Underground

January 06, 2026