A character of Paul Bowle inThe protecting sky left one thing clear. It’s not the same being a tourist that being a traveler. Travelers never know when they are returning home. They don’t know if they are ever returning.

No one has ever been able to turn Matanzas, despite its geographical and architectural beauty, into a tourist site. One goes to Matanzas to stay, if not physically, metaphysically. Every true traveler has brought in his/her body, and has given himself in body and soul. The body may or may not stay, but souls do stay. No one has seen Matanzas from the Top like Swedish Fredrika Bremer did, no one has written letters from Matanzas like hers. Prince Alejo from Russia believed to have found the genesis site in the Yumuri valley. Until the present, none engraving about Matanzas has been better than that by French Frederik Mialhe. Placido, from Havana, discovered the beauty of women tobacco growers from Yumuri. Heredia could see the Loaf Mountain of Matanzas (Pan de Matanzas) from a spot that no other human could see it. Roberto Diago found in the African roots of this city the definition of his poetry; Fidelio Ponce, the sepia light of his girls. Victor Manuel imagined a more universal Saint John than provincial Milanes was; Osborne envisioned a future of Matanzas that is still to come. Federico Smith transcribed the symphony that had waited for 281 years for his geniality to take dictation; Ñico Rojas found chords, the peculiar harmony of his music. It was another woman from Havana, Marta Valdes, who discovered, in the danzon music, that God realized on the eighth day of creation that the world was missing a city and he founded Matanzas.

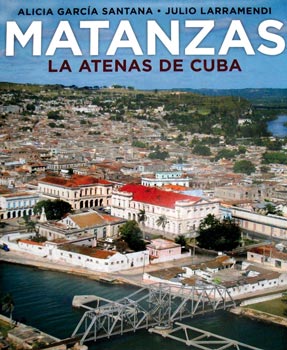

Alicia Garcia Santana, who was not born in Matanzas either, overflies Matanzas to give us, like in Carroll’s novel, a children’s story that looks like a surreal novel. Because the history of this city, though told with every scientific detail and the support of a culture and knowledge that places the author among the most rigorous authorities of the history of the colonial architecture in Cuba, leaves us as perplexed as a fable, as a fiction reading, with its usual suspense, heroic characters, and pitched battles. One unpublished Matanzas is the one presented to us by the lively prose of Alicia Garcia Santana and the lens of Julio Larramendi.

Alicia Garcia Santana, who was not born in Matanzas either, overflies Matanzas to give us, like in Carroll’s novel, a children’s story that looks like a surreal novel. Because the history of this city, though told with every scientific detail and the support of a culture and knowledge that places the author among the most rigorous authorities of the history of the colonial architecture in Cuba, leaves us as perplexed as a fable, as a fiction reading, with its usual suspense, heroic characters, and pitched battles. One unpublished Matanzas is the one presented to us by the lively prose of Alicia Garcia Santana and the lens of Julio Larramendi.

The history of Matanzas, the Athens of Cuba, is told in details by the artwork accompanying or, even better, complementing the study. Julio Larramendi encompasses planes that overrate the beauty of Matanzas’ geography, of its singular layout and peculiar architecture, without forgetting that the goal is not only to highlight the splendor but also and, above all, to provide a graphs service that should be rigorously subjected to the scientific interest. And in this field, the artist has quite a lot of experience with books about Cuban architecture, fauna and flora, our geography. Nonetheless, I insist, his pictures tell a story as well.

This book can be seen as a big album of Matanzas containing not only the best photos ever made of the city, but also a large number of maps, planes, engravings, oils, postcards, many of them had never been published before, which demonstrate a thesis, and as usual, plant new concerns.

In 320 pages and with more than 750 graphic images, the authors manage to penetrate the history of the first city founded to the interest of the colony and by explicit desire. Alicia, who is a sharp investigator but also a great teacher, introduces us little by little, from the very beginning of its colonial history, in the labyrinths that led to the need of fortifying Matanzas Bay and creating a town there in 1693.

The strategies followed by the founders to lay a city in-between two rivers, the San Juan and the Yumuri, precisely at the mouth, looking out the radiant bay. The hurdles caused by the rivers themselves and the surrounding wet lands, the beautiful but complex geography enhanced the abilities of architects, engineers, construction workers and civil authorities to attain the later economic, social and cultural development of the city are exposed in the three chapters making up the structure of the book offering an intelligent analysis and broad documentation.

Following the preface by Eusebio Leal Spengler, Historian of the City of Havana, and the prologue by Ercilio Vento, Historian of the City of Matanzas, Alicia Garcia Santana’s book opens with a sort of porch that she titled “Bridge to Modernity,” in which she gives hints about the interests of her study to lead us later into the first chapter dedicated to “Urbanism of the Indian Laws for a new city.” There we learn details about the foundation, parallel to the fortification of the bay including as well the San Severino Castle, the San Jose de la Vigia Fort, at the foundation square, the Battery or the Peñas Altas Castle and the El Morillo Battery. Images and texts show the consolidation of the foundational site and the urban transformation of the area in-between the rivers, the emerging of new neighborhoods and squares, as in addition to the Colon (or La Vigia) Square, the King (or Liberty) and Fernando VII squares came later, as well as the Matanzas Park (“Rene Fraga Moreno”) and the emergence of two neighborhoods outside the area in-between the rivers: New Town of Saint John and the New Town of Versalles, wrapping up the population project around Matanzas Bay.

Alicia closes the chapter with a section titled “From the ideas to urban reality” in which she supports –through broad and deep analysis of the emerging and characteristics of the Cuban cities previously founded, and the particularities of the new city– the thought that Matanzas is “the best expression of the ideals advocated by the Population Laws of 1573 in our lands” which makes it an “extraordinary city, pride of the Cuban nation.”

The second chapter is, theatrically speaking, the climax of the book: “An illustrated architecture for the first modern city of Cuba.” In this chapter the researcher demonstrates her thesis that Matanzas is the cradle of the Cuban urban modernity. Related to it is the work of Julio Sagebien, a French man who contributed a lot to the Cuban architecture (Havana: Aldama Palace), (Trinidad: Main Square), and who according to Garcia Santana played a relevant role in the new image of Matanzas in the first half of the 19th century. The Customs building, his first architectural work, opened a new epoch for local architecture. The author gives details about important public works in which Sagebien left his renovating mark reaching bridges, railroads, residences, barracks, hospitals… Matanzas could be easily called –says the author–, “the city of Sagebien.”

To the bridges of the 19th century the authors dedicate a space in the book. Matanzas is labeled as the city of bridges not only because of the existence of the best set of bridges in the 19th and 20th centuries in Cuba, but also because the big bridge the city itself is in architecture, a lever for the social, economic and cultural development of the nation.

Great public works and great engineers, architects, construction workers are mentioned for their work in this chapter of the book. A significant space is reserved to Italian architect Daniel Dall’Aglio, who left pieces like the majestic Sauto Theater, one of the best of the Americas, and the no less impressive church of Saint Peter of Versalles.

As relevant as Sagebien, who was a key figure in the building of the new Matanzas in the first half of the 19th century, was Spanish architect Pedro Celestino del Pandal, the great builder of the second half of the century, creator of La Concordia bridge, which became symbol of the city. Pandal is, the author stresses, one of the beginners of the era of architects in the history of Cuban constructions. It was this architect who initiated the urban transformation of Matanzas in the crucial times.

The third and last chapter of the book, under the title: “Matanzas’ criolla and neoclassic house” provides an exhaustive tour of the houses of the city. Having overflowed Matanzas through a lens and Alicia’s wise words, we enter now the intimacy of a home or public institution, sneaking every detail presented by the author showing the development and splendor of Matanzas’ typical house, its peculiarities. It feels so nice that makes authors and readers feel like they are attending a gathering in a unique patio talking about neoclassicism as expression of urban unity; traditional, proto-neoclassic, late neoclassic and eclectic houses. All of this explained with scientific rigor, clear language and precise images.

The book can be read by a common reader and appreciated in all of its knowledge because it is written without didacticism, having a long teaching experience; without being smug, having so much learning. A visual book. Nice to be paged. Nice to the eye. A book for the most demanding scholar. A reference book. Arsenal of wisdom and beauty that fill us with strength. Notes, quotes and references. Abundant bibliography. Vade mecum of Matanzas. A piece of work to which we will always return.

Matanzas, the Athens of Cuba ends with a claim and a sentence: To Save Matanzas. “Avoid the loss of such a valuable cultural legacy, because Cuba will not be the same without its Athens.”

In Matanzas, on May 24, 2010

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022